Святки – традиционное православное рождественское празднество. Начинались они с 6 января (Рождественского Сочельника) и длились 12 дней до праздника Крещения Господня (Богоявления) 19 января. Первая неделя Святок называлась «святая», а вторая – «страшная». В святочных верованиях сплелись христианские и языческие понятия, а древние сказания повествовали о том, что в период Святок Бог, раскрыв врата ада, дабы отметить Рождество Христово, выпустил нечистую силу. Есть две традиции празднования Святок – языческая и христианская. Рассмотрим каждую в отдельности.

Языческие Святки — Святовит и Коляда

У славян-язычников (до принятия Русью христианства) этот период года был посвящен верховному небесному богу Святовиту (Белбогу), отсюда и название «святки». Из других источников, старославянское слово «святки» означает «души предков». В дохристианские времена языческие святочные обряды представляли собой гадания о будущем и магические заклинания на весь год, их отличительная черта – бытовые приметы, гадания и обряды, целью которых было узнать судьбу будущего урожая, поголовья скота.

На Святки у древних славян приходил Коляда, который олицетворял собой начало годичного солнечного цикла. Для Коляды разжигали костры со священным огнем, которые горели 12 суток подряд. Вокруг костров водили хороводы, плясали, пели обрядовые песни-колядки, славящие Коляду и зазывающие солнце. С горы спускали «огненные» колеса, символ солнца. Молодежь рядилась в новую одежду, которая была символом обновления природы, и устраивала игрища и гадания.

В святочные дни запрещалось работать после захода солнца – люди верили, что за это работающего наказывал Бог. Двенадцатидневный святочный цикл считался временным рубежом – заканчивался старый, и начинался новый солнечный год. Старый год уже ушел, а новый еще не наступил – будущее было неопределенно, поэтому стиралась временная грань между миром мертвых и живых. Считалось, что в дни Святок по земле гуляли души мертвых и нечистая сила, которая была в эти дни особенно опасной.

Христианские Святки — от Рождественского Сочельника до Крещения Господня

У христиан Святки начинались с Рождественского Сочельника, который завершал сорокадневный Рождественский пост (святая Четыредесятница). В этот день необходимо строго поститься, пока на небе не появится первая звезда, символизирующая Вифлеемскую Звезду, указавшую библейским волхвам путь к Младенцу Иисусу. А когда в родительском доме собиралась вся семья — праздновали Рождество Христово.

Вечером в Сочельник неженатые парни и незамужние девушки, распевая песни-колядки, гурьбой ходили по домам, желали благополучия хозяевам, а взамен выпрашивали угощения или деньги. Считалось, как одарят колядующих, такой и достаток будет в доме. Поэтому в каждой семье всегда ждали гостей с колядками и готовили заранее угощения. С рассветом строгого поста уже не было и в помине.

Все двенадцать дней Святок продолжались гулянья, игрища и, разумеется, святочные гадания, а как же без них? Предметом этих гаданий всё чаще становились не погода, не урожай и даже не поголовье скота, как это было во времена предков. Молодёжь гадала, интересуясь своей судьбой, ведь наступал сезон сватовства и свадеб. Зимние свадьбы на Руси были очень распространены.

10 января — Домочадцев день. Начинался Рождественский Мясоед — время самых изобильных застолий. Длился этот «праздник живота» до самой Масленицы. Именно во время Мясоеда накрывались столы для дорогих гостей, засылали сватов, торопились отпраздновать свадьбу или хотя бы назначить дату свадьбы (свадебный сговор).

11 января — Страшный день. Считалось, что именно в этот день силён разгул нечистой силы. Родителям полагалось читать защитные молитвы на детей. Но молодёжь ничуть не боялась Страшного дня и проводила его очень весело.

Вечер 13 января — Васильев вечер, Васильева Коляда, канун Нового Года по старому стилю. Самое удачное время для святочных гаданий. Канун Нового года еще назывался Щедрый вечер. Хозяйки накрывали обильный стол и чествовали каждого гостя, зашедшего в дом. В Щедрый вечер молодежь тоже ходила по домам и колядовала, но по-особенному. Распевали «Щедривки» («Щедровки») Как и в колядках, в щедривках желали счастья и благополучия щедрым хозяевам. Припев у щедривок был традиционный: «Щедрый Вечер, Добрый Вечер, Добрым людям на здоровье!»

14 января — День святителя Василия Великого, Новый Год по старому стилю, или, как мы его называем, Старый Новый Год.

18 января — Крещенский Сочельник, канун праздника Крещения Господня (Богоявления). Весь день необходимо держать строгий пост. Вечером 18 января начинается всенощное бдение в церкви, посвященное великому празднику Крещения Господня и состоящее из великого повечерия, литии, утрени и первого часа. В это же время по особому чину в храмах начинается Великое Водоосвящение воды. Крещенская вода называется Великой Агиасмой.

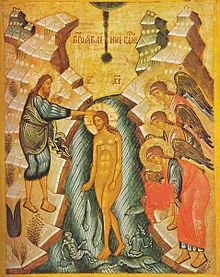

19 января — Крещение Господне, Богоявление. Древние названия этого праздника — Епифания (Явление) и Теофания (Богоявление). Это один из двунадесятых святых праздников. В праздник Крещения (Богоявления) производится освящение ближайших рек и других источников, откуда берется вода для питья. К природным источникам воды следует церковное шествие, называемое Крестный ход на Иордан. Чтобы освятить воду, во льду реки делают прорубь в виде креста — иордань. После водоосвящения многие верующие отваживаются окунуться в эту ледяную купель, чтобы смыть грехи и возродиться душой в этот светлый праздник.

Так завершаются Святки — 12 праздничных дней от Рождества Христова до Богоявления.

Святки (святые дни) — двенадцать дней после праздника Рождества Христова, до праздника Богоявления (7-19 января)

Святки всегда являлись основным зимним праздником на Руси. В Святки, все 12 дней, никто не брался ни за какую работу, боясь несчастья. По поверьям, с началом Святок с того света возвращаются души умерших, начинаются потехи нечистой силы и ведьм, которые справляют шабаш и веселятся с нечистыми. К слову, именно потому что мертвые в этот период приходят в наш мир, святочные гадания считались самыми верными. Ведь кто еще может знать правду, как не духи. Православная церковь, суровая к гадальщикам, в эти дни меняет свой гнев на милость. Считается, что в период от Рождества до Крещения гадание перестает быть бесовским действием, а становится просто забавой.

Традиционно Святки делились на две части — «святые вечера» (от Рождества до Васильева вечера 7-14 января) и «страшные вечера» (с ночи под Новый год и до Крещения Господня 14-19 января).

Несмотря на то, что весь святочный период считался в народе временем «без креста», то есть временем, когда только что родившийся Иисус еще не был крещен, особый разгул нечистой силы связывался именно со «страшными вечерами», что отразилось в соответствующем названии. По народной легенде, «в эти страшные вечера /…/ Бог на радостях, что у Него родился Сын, отомкнул все двери и выпустил чертей погулять. И вот, черти, соскучившись в аду, как голодные, набросились на все грешные игрища и придумали, на погибель человеческого рода, бесчисленное множество развлечений, которым с таким азартом предается легкомысленная молодежь» (Максимов С.В., 1994, с.267). В этой легенде сквозь призму христианской морали находят отражение архаичные представления о Святках как о периоде, отмеченном признаком хаотичности в связи с процессом формирования миропорядка, «издержкой» которого является проникновение в мир людей существ «иной» природы.

Святки были насыщены различного рода обрядами, магическими действиями, запретами, гаданиями. С их помощью старались обеспечить благополучие на весь год, выяснить свою судьбу, задобрить «родителей» — умерших предков, обезопасить себя от нечистой силы. Так, например, в надежде на увеличение плодовитости скота в сочельник — канун Рождества — выпекали из теста «козульки» («коровки») — печенье в виде фигурок животных и птиц. В надежде на будущую счастливую жизнь ставили сноп в красный угол избы, разбрасывали солому по полу, кормили кутьей куриц, обвязывали лентами фруктовые деревья. Самым ярким обрядовым действием, с которого начинались святки, был обряд колядования, представлявший собой театрализованное зрелище, сопровождавшееся пением песен — пожеланий, величаний хозяевам. Колядовали обычно в ночь на Рождество, на Васильев день, в крещенский сочельник.

Святки отмечались по всей России и считались молодежным праздником. Особенно яркими и веселыми, наполненными музыкой, пением, играми они были в деревнях северных и среднерусских губерний Европейской России, а также в Сибири. В западнорусских и южнорусских губерниях их празднование было более сдержанным и спокойным. Святки отмечались обычно в вечернее и ночное время.

Считали, что работающего в святки накажет Бог: у человека, который в святочные вечера плетет лапти, скот будет кривой, а у шьющего одежду — скот ослепнет. Тот же, кто занимается в святки изготовлением обручей, коромысел, полозьев для саней, не получит приплода скота. Святочный цикл воспринимался как пограничный между старым и новым солнечным годом, как «плохое время», своего рода безвременье. Старый год уходил, а новый только начинался, будущее казалось темным и непонятным. Верили, что в это время на земле появлялись души умерших, а нечисть становилась особенно опасной, так как в период безвременья граница между миром людей и враждебным им миром нечистой силы была размыта.

Во время святок молодежь устраивала игрища, на которые приглашались парни и девушки из других деревень. Развлечения и игры этого периода носили ярко выраженный эротический характер. Кроме того, в Крещение в больших селах проходили смотры невест, то есть показ девушек брачного возраста в преддверии следующего за святками месяца сватовства и свадеб.

Святочный период можно назвать временем активного формирования брачных пар нового года, чему способствовало проведение почти каждый вечер, кроме сочельников, игрищ молодежи. Здесь парни и девушки имели возможность внимательно присмотреться друг к другу. К тому же, Святки являлись одним из принятых в традиции периодов гощения девушек у родственников или подруг, живущих в более крупных деревнях или селах, где вероятность найти брачного партнера была значительно реальней. Девушки старались привлечь к себе внимание с помощью ярких праздничных нарядов, умения петь, танцевать, поддерживать беседу, а также, демонстрируя свой характер, веселый и бойкий, но в то же время и скромный, что в народных представлениях считалось эталоном девичьего поведения.

В рождественский сочельник на деревенских улицах Центральной и Южной России около каждого дома жгли костры из соломы, навоза, чтобы погреть умерших, якобы приходивших в деревню к своим потомкам. В некоторых деревнях средней полосы Европейской России в костры бросали липовые веники, чтобы покойники могли попариться в бане. Умерших приглашали также на главные святочные трапезы, проходившие поздно вечером в канун Рождества, Васильева дня и Крещения.

На стол для них ставили кутью из распаренных зерен пшеницы и ягод, овсяный кисель и блины, то есть блюда, характерные для поминальных трапез. Верили, что умершие, обогретые и накормленные потомками, обеспечат им процветание в наступающем новом году. Приход нечистой силы разыгрывался в ряженье, а также в играх, характерных для святочных вечерок. Магические действия по защите людей и их домов от нечистой силы были особенно характерны для второй недели святок, ближе к Крещению. В эти дни более тщательно, чем обычно, подметались избы, а чтобы в мусоре не спряталась нечистая сила, его выносили подальше от деревни.

Дома и хозяйственные постройки окуривали ладаном и окропляли святой крещенской водой, на дверях и воротах ставили мелом кресты; обходили с топорами скотину, выпущенную хозяевами в Крещение из хлевов на улицу. К крещенскому сочельнику и Крещению приурочивались обряды проводов умерших предков и изгнания нечистой силы. Это могло проходить по-разному. Например, в некоторых губерниях парни выгоняли нечистую силу громкими криками, размахивая метлами и ударяя кнутами по заборам. Водосвятие в крещенский сочельник и в Крещение также рассматривалось как один из способов изгнания нечистой силы из рек, озер, прудов и колодцев.

Представления о «плохом» времени нашли отражение в названии «страшная неделя» применительно ко второй половине святок; первая половина святок, которая начиналась Рождеством Христовым, называлась «святой неделей». Языческие представления соединились с христианскими: в легендах рассказывалось, что Бог открыл врата ада, чтобы бесы и черти тоже могли попраздновать Рождество.

Сотрудники Русского этнографического музея утверждают, что в дохристианской Руси святки связывали с именем бога Святовита. Что это за бог и почему ему выделили особый двухнедельный праздник, ученые спорят до сих пор. Предполагают, что «Святовит» — просто одно из имен верховного бога Перуна. Как бы там ни было, славяне всячески старались этого бога ублажить, в первую очередь затем, чтобы он послал обильный урожай. На святки Святовиту полагалось оставить немного праздничной еды, которую специально для него бросали в печь. Славяне верили, что в начале зимы духи богов и души предков спускаются на землю, и в этот момент у них можно «выпросить» и обильный урожай, и пригожего мужа, и денег, и вообще все, что угодно.

Христианская традиция празднования святок также известна с древности. Еще в IV веке греческие христиане отдыхали, веселились и сугубо праздновали две недели после Рождества (по одной из версий, слово «святки» произошло от глагола «святить», так как на святки народ «святит», то есть прославляет Христа и Рождение Христа). Особое внимание уделялось тому, чтобы радостное настроение было у всех: бедняков, рабов, заключенных. В Византии стало обычаем на святки приносить еду и подарки в тюрьмы и больницы, помогать бедным. Упоминания о святках как об особом послерождественском торжестве мы встречаем у Амвросия Медиоланского, Григория Нисского и Ефрема Сирина.

С пришествием христианства святки на Руси тоже начали наполняться новым смыслом. Тем не менее отношение Русской Церкви к святочным гуляниям всегда было неоднозначным. Многие иерархи высказывались не только против гаданий, но и против колядования и обычая «рядиться» на основании постановления VI Вселенского собора, которое гласит: «Прибегающие к волшебникам или другим подобным, чтобы узнать от них что-либо сокровенное, да подлежат правилу шестилетней епитимьи (т. е. на шесть лет отстраняются от Причастия)… пляски и обряды, совершаемые по старинному и чуждому христианского жития обряду, отвергаем и определяем: никому из мужей не одеваться в женскую одежду, не свойственную мужу; не носить масок». Тогда сторонники святок придумали остроумное «решение» проблемы: на Крещение во льду реки или озера делали прорубь в форме креста, и все население деревни окуналось в нее, смывая с себя грехи, совершенные на святках.

Со временем религиозный смысл языческих традиций окончательно забылся, и святки стали временем, когда народ сугубо славит Рождество и милосердие Господа, пославшего на Землю Иисуса Христа. От древних дохристианских святок осталось лишь зимнее, чисто русское неуемное веселье.

Любимое народное развлечение на святки — рядиться и колядовать. На Руси, а затем и в Российской империи молодежь в святочные вечера собиралась вместе, переодевалась в зверей или мифологических персонажей вроде Иванушки-дурачка и шла колядовать по деревне или городу. Кстати, это одна из немногих святочных традиций, которые выжили в послепетровскую эпоху, несмотря на то что большая часть населения переместилась в города. Главным персонажем среди колядующих всегда был медведь. Им старались одеть самого толстого парня деревни или околотка. Ряженые заходили поочередно в каждую избу, где горел свет. Подростки и дети пели рождественский тропарь, духовные песни, колядки… Колядки — это что-то вроде кричалок Винни-Пуха, в которых восхваляется хозяин дома и посредством которых у этого самого хозяина выпрашиваются угощение. Песни часто сочинялись прямо на ходу, но существовали в этом искусстве традиционные, идущие из стародавних времен правила. Хозяина, например, величали не иначе, как « светел месяц » , хозяюшку — « красным солнцем » , детей их — « чистыми звездами » . Впрочем, кто умел, придумывал величания более выразительные: « Хозяин в дому — как Адам на раю; хозяйка в дому — что оладьи на меду; малы детушки — что виноградье красно-зеленое… » Колядующие обещали богатый урожай и счастливую жизнь тем, кто дает угощение, и всяческие бедствия скупым. Иногда в песнях звучали даже угрозы: « Кто не даст пирога — с ведем корову за рога, к то не даст ветчины — тем расколем чугуны… » Все это, конечно, в шутку. Иногда пели абсолютно, даже нарочито бессмысленные приговорки. Хозяева принимали гостей, давали кто что мог.

Еще один святочный обычай — собираться всей семьей по вечерам, звать гостей (как можно больше), рассказывать сказки и загадывать загадки (как можно более сложные). Эта традиция, как и колядование, жила не только в деревнях, но и среди городского дворянства. Литературовед Ю. М. Лотман в своих комментариях к «Евгению Онегину» пишет, что было принято разделять «святые вечера» и «страшные вечера» (первая и вторая недели после Рождества соответственно). В «святые вечера» устраивали веселые ночные посиделки, в «страшные вечера» — гадали. Молодежь собиралась поплясать, днем — покататься на санях, поиграть в снежки. Кстати, после святок всегда было много свадеб. «В посиделках, гаданиях, играх, песнях все направлено к одной цели — к сближению суженых. Только в святочные дни юноши и девушки запросто сидят рука об руку», — писал фольклорист И. Снегирев книге «Песни русского народа».

Самая «антиобщественная» святочная традиция — «баловство». Дети и подростки собирались по ночам большими ватагами и озорничали как могли. Классической шуткой было заколотить снаружи ворота в каком-нибудь доме или разворошить поленницу дров. Еще одно развлечение — ритуальное похищение чего-либо. Похищать можно было все что угодно, но обязательно с шумом и песнями, а не тайком. В советские времена, несмотря на все запреты, нередко «похищали» колхозные трактора. Сразу же после праздников их, разумеется, возвращали на место.

Последние дни Святок были посвящены подготовке к Крещению. Лучшие деревенские мастера прорубали крестообразную прорубь в замерзших водоемах и украшали ее узорами изо льда.

История государственного урегулирования святочных празднеств очень разнообразна. Первые законодательные акты по этому поводу были изданы при Петре I . «Царь Петр очень любил колядование и сам с удовольствием ходил по домам в компании ряженых. А тех, кто отказывался принимать участие в этой забаве, приказывал бить плетьми», — рассказывают сотрудники Русского этнографического музея.

После смерти Петра I отношение к колядованию резко изменилось. Во второй половине XVIII было даже запрещено колядование и ряжение: «Запрещается в навечерие Рождества Христова и в продолжение святок заводить, по старинным идолопоклонническим преданиям, игрища и, наряжаясь в кумирские одеяния, производить по улицам пляски и петь соблазнительные песни», — гласит императорская грамота. Скорее всего, власти просто боялись массового пьянства и хулиганств, а не беспокоились о нравственном облике ряженых. Как бы там ни было, это был, наверное, один из наиболее часто нарушаемых законов Российской империи, и о нем вскоре забыли.

После революции никаких специальных постановлений на этот счет не было, однако святки, как и другие праздники, носящие религиозный характер, постоянно преследовались, поэтому вскоре ушли из городов в далекие глухие деревни.

Перед Крещением большинство злобствующей нечисти отступало. Дабы окончательно избавиться от неприятностей народ устраивал Проводы святок. Люди с криками били метлами по углам, стучали по заборам, скакали на конях вдоль сила, стреляли в небо во дворах. А в конце кричали: «Иди уже, колядка, с Богом, а через год снова приходи!».

Святки являлись своего рода энергетическим импульсом, дающим начало очередному витку жизни природы, в том числе и каждого отдельного человека как части природы. Помимо этого, две святочные недели представляли собой важнейший период, в пределах которого в максимально концентрированной форме происходила «передача» от старших младшим коллективного знания, то есть закрепленного в веках знания многих поколений. Получение новыми поколениями этого знания делало возможным сохранение и дальнейшее развитие культурной традиции. В этом плане чрезвычайно важной в святочное время была роль стариков, несмотря на сложившееся в народном сознании восприятие Святок как молодежного праздника. Так как старики, по народным представлениям, из всех социовозрастных групп общины были наиболее близки к «иному» миру, они закономерно оказывались посредническим звеном между молодостью и вечностью, то есть поддерживали традицию и передавали свой опыт и знания молодому поколению.

Святки — это две недели зимних праздников, которые начинаются в Рождественский Сочельник 6 января и продолжаются до Крещения 19 января. В христианской традиции Святки — это празднование Рождества Христова. В эти дни на Руси гадали и пели коляды. На Руси люди всегда считали: как святочную неделю проведешь, так и вся твоя жизнь в этом году пройдет. Именно по этой причине в старину люди старались реализовать все свои планы в эти дни. Если вы хотите всю жизнь жить богато, то надевайте всю неделю только самые лучшие свои вещи. Хотите кушать вкусно, тогда в святочную неделю ешьте то, что вы любите больше всего. А если вы хотите, чтобы в доме всегда царили мир и любовь, тогда говорите друг другу ласковые и нежные слова в течение всей недели.

Сон, приснившийся на святки, обязательно будет вещим. В этот день любые сведения, полученные из потустороннего мира, являются предсказанием. Весёлых вам выходных!

Святки – это время от Рождества Христова до праздника Крещения Господня. Эти два праздника соединены чередой праздничных дней. Церковь по любви к людям дает праздник развернутый во времени. В эти дни можно причащаться, не соблюдая пост со всей строгостью. Все дни наполнены удивительной радостью праздника Рождества Христова.

Эти дни хорошо посвятить близким, семье, детям и родителям и тем одиноким людям, у кого нет близких… А вот проводить Святки – святые дни – за бездарным просмотром телевизора – это значит растратить тот дар, который нам дает Господь.

Протоиерей Александр Ильяшенко

- Богослужения

- Святки Богословско-литургический словарь

- Святки Г.И. Шиманский

- Святки схиархим. Иоанн (Маслов)

- Можно ли в святки молиться за усопших? иеромонах Иов (Гумеров)

- Святки прот. Григорий Дьяченко

- Традиции

- Как христиане святки проводят, и как надо проводить их прот. Николай Успенский

- Как провести Святки? прот. Александр Ильяшенко

- Позволительно ли рядиться в святки? прот. Григорий Дьяченко

- О буйном веселье на святках и маслянице прп. Стефан Филейский

- Что нужно знать о гаданиях на святки? свящ. Георгий Максимов

- Художественная литература

- Святочные рассказы Н.С. Лесков

- Святочные рассказы В.И. Немирович-Данченко

- Дары волхвов О. Генри

- Чудесный доктор А. И. Куприн

- Стихи о Рождестве Христовом

Свя́тки (святые дни) – период от праздника Рождества Христова до Крещенского сочельника (7–17 января включительно). Они называются также святыми вечерами.

Святить период между Рождеством Христовым и Богоявлением Церковь начала с древних времен. Указанием на это могут служить 13 бесед св. Ефрема Сирина, произнесенных им от 25 декабря по 6 января, а также слова св. Амвросия Медиоланского и св. Григория Нисского.

Продолжительность Святок

Какова продолжительность Святок? Когда они начинаются и когда заканчиваются? На эти, казалось бы, простые вопросы в церковной литературе даются разные ответы. Фактически существует 4 (!) точки зрения на продолжительность Святок:

I. 7–17 января (11 дней). Эта точка зрения отражена на нашем сайте, часто такая продолжительность указывается в календарях как сплошной период, в течение которого нет постных дней. Такая точка зрения лишена недостатков: во все дни периода совершаются богослужения с праздничными особенностями, поста нет.

II. 8–19 января (12 дней). В литературе очень популярно утверждение о 12 дней продолжительности Святок; вероятно, это объясняется приверженностью символическому значению числа 12. В частности, известный литургист середины XX века Г. И. Шиманский указывает для Святок период от Собора Богородицы до Крещения Господня. Однако в такой точке зрения два изъяна 1) в Святки включается день строгого поста – Крещенский сочельник; 2) почему-то Крещение Господне включается в период Святок, тогда как равный ему по степени торжественности праздник Рождества Христова – нет.

III. 7–18 января (12 дней). Эта точка зрения отражается на некоторых электронных ресурсах (как правило, нерелигиозных). Эта точка зрения – фактически вариация предыдущей, имеет те же недостатки: в период Святок включается Крещенский Сочельник, а из двух Господских праздников один (Рождество Христово) считается, тогда как другой – нет.

IV. 7–19 января (13 дней). В этом случае Святками считается весь период от Рождества Христова до Богоявления, такую позиция отражена в книге схиархимандрита Иоанна (Маслова). (Впрочем, сам автор допускает ошибку: говорит о 12 днях Святок, хотя по факту указывает период в 13 дней). В таком подсчете только один недостаток: в Святки включается день строгого поста – Крещенский сочельник.

Три периода святок их богослужебные особенности

Хотя термин «святки» обозначает единый 11-тидневный период с 7 по 17 января (по новому стилю), его можно разделить на три временных отрезка на основании богослужебного содержания:

7–13 января – праздник Рождества Христова и его попразднства;

14 января – Обрезание Господне по плоти и святителя Василия Великого;

15–17 января – предпразднство Богоявления.

Богослужебные и уставные особенности всего периода Святок

- Пост в среду и пятницу отменяется;

- Коленопреклонение не совершается;

- Венчание брака не совершается;

- Октоих в седмичные дни не поется;

Святочные обычаи и традиции

С периодом Святок связаны следующие обычаи, расположим их в порядке от более нормальных и приемлемых к спорным и нецерковным:

Хождение в гости

Праздновать Рождество Христово, делиться друг с другом этой радостью, позволить себе определенное утешение после долгого поста – не только законный, и но вполне похвальный образ проведения этих дней. Господь в Пятикнижии повелевает: «Семь дней празднуй Господу Богу твоему, на месте, которое изберет Господь, Бог твой; ибо благословит тебя Господь, Бог твой, во всех произведениях твоих и во всяком деле рук твоих, и ты будешь только веселиться» (Втор. 16:15). И хотя буквально это сказано о празднике Кущей, можно вполне распространить эти слова на праздничные периоды Церкви, в первую очередь на Светлую седмицу и на Святки.

Рождественские сценки, мероприятия в воскресных школах

Понятно, что различные постановки и рождественские сценки основаны на неканонических и подчас фантастических реалиях, все же определённый просветительский и благотворный эффект они имеют.

Колядование

Есть обычай ходить по домам и рассказывать различные рождественские колядки. При этом ходят как правило дети (под руководством и присмотром взрослых), поздравляют с Рождеством Христовым, поют песни и рассказывают стихотворения, а хозяева жилищ одаривают символическими угощениями. Здесь оценка должна быть взвешенной: есть колядки по содержанию вполне христианские, но немало и совершенно светских, в которых нет никакого религиозного смысла. В последнем случае колядование превращается в обычное попрошайничество и вряд ли может быть одобрено христианским сознанием.

Представления, гуляния

Есть обычай наряжаться в различные шутовские наряды и устраивать представления, гуляния. Эта практика является рудиментом языческих верований, согласно которым начало года считалось временем, когда у богов можно выпросить хороший урожай. Также важно, что в Древнем Риме и в Византии подобные мероприятия были связаны с празднованием январских календ. В России святочные гуляния были распространенными вплоть до XVIII века. Известно, что император Петр I сам любил эти гуляния и заставлял принимать в них участие своих приближенных. Однако во 2‑й половине XVIII века многие обычаи, связанные со святочными гуляниями, были запрещены. Причем причины запрета были не столько богословскими, сколько вызваны практической необходимостью: сами гуляния и связанные с ними разнузданность, анархия рассматривались как общественно опасные. Для нас особенно важно, что подобного рода действия запрещаются 61‑м и 62‑м правилами VI Вселенского Собора. Особенно обратим внимание на следующие слова: «Той же епитимии надлежит подвергати и тех, которые водят медведиц, или иных животных, на посмешище и на вред простейших, и, соединяя обман с безумием, произносят гадания о щастии, о судьбе, о родословии, и множество других подобных толков» (правило 61) и «Так называемые календы, вота, врумалиа, и народное сборище в первый день месяца марта, желаем совсем исторгнути из жития верных. Такожде и всенародныя женския плясания, великий вред и пагубу наносити могущия, равно и в честь богов, ложно так еллинами именуемых, мужеским или женским полом производимыя плясания и обряды, по некоему старинному и чуждому христианскаго жития обычаю совершаемые, отвергаем, и определяем: никакому мужу не одеватися в женскую одежду, ни жене в одежду мужу свойственную; не носити личин комических, или сатирических, или трагических» (правило 62).

Гадания

Распространен предосудительный обычай гаданий во время Святок о судьбе, о будущем супруге и пр. Понятно, что любые гадания являются языческими обычаями, связанными с волхованием и общением с нечистыми духами, потому ни в коем случае не приемлемы для христиан.

Цитаты о святках

«Дух Христов, – по замечанию святителя Филарета (Дроздова), – не враг благозаконных радостей»; в невинных играх и забавах отдыхает душа, истомленная: шумом суеты, поддерживается и питается чувство дружбы среди людей; с христианской точки зрения дозволительны игры и развлечения, которые не нарушают чистоты мыслей, чувств и слов, не оскорбляют слуха и очей, не унижают человеческого достоинства. Но нужно твердо помнить, что «где нега и роскошь, как учит св. Иоанн Златоуст, где пьянство и всякие забавы, там нет ничего твердого, а все шатко, непостоянно. Слушайте это вы, которые любите смотреть на пляшущих и тем растлеваете свое сердце».

В «святые дни» должно усиленнее стараться не отвлекать ума и сердца своего от святых помыслов, чувствований и деяний; а это обязывает каждого устранять себя от всякого шума буйного веселия. Не разгул и шумное мирское веселие делает праздник Христов радостным и приятным для нас, а утешающая душу, услаждающая и веселящая сердце благодать Божья, даруемая свыше лишь тем, которые удаляют себя от всего того, чем оскорбляется любовь Божья, что отвращает от нас благоволительный взор Отца Небесного, чем бесчестится святое и достопоклоняемое имя Христово, чем нарушается святость праздника».

Настольная книга священнослужителя

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Twelve Days of Christmas | |

|---|---|

The Adoration of the Magi, Fresco at the Lower Church of the Basilica of San Francesco d’Assisi in Assisi, Italy. |

|

| Observed by | Christians |

| Type | Christian |

| Observances | Varies by denomination, culture, and nation |

| Date | 25 December – 5 January, inclusive |

| Frequency | annual |

| Related to | Christmas Day, Christmastide, Twelfth Night, Epiphany, and Epiphanytide |

The Twelve Days of Christmas, also known as Twelvetide, is a festive Christian season celebrating the Nativity of Jesus. In some Western ecclesiastical traditions, «Christmas Day» is considered the «First Day of Christmas» and the Twelve Days are 25 December to 5 January, inclusive,[1] with 6 January being a «thirteenth day» in some traditions and languages. However, 6 January is sometimes considered Twelfth Day/Twelfth Night with the Twelve Days «of» Christmas actually after Christmas Day from 26 December to 6 January.[2] For many Christian denominations—for example, the Anglican Communion and Lutheran Church—the Twelve Days are identical to Christmastide,[3][4][5] but for others, e.g. the Roman Catholic Church, Christmastide lasts longer than the Twelve Days of Christmas but the Christmas itself lasts one day on December 25.[6]

History[edit]

In 567, the Council of Tours «proclaimed the twelve days from Christmas to Epiphany (i.e. to just before midnight 5 January as Epiphany begins 6 January) as a sacred and festive season, and established the duty of Advent fasting in preparation for the feast.»[7][8][9][10] Christopher Hill, as well as William J. Federer, states that this was done in order to solve the «administrative problem for the Roman Empire as it tried to coordinate the solar Julian calendar with the lunar calendars of its provinces in the east.»[clarification needed][11][12]

Eastern Christianity[edit]

The Armenian Apostolic Church and Armenian Catholic Church celebrate the Birth and Baptism of Christ on the same day,[13] so that there is no distinction between a feast of Christmas and a feast of Epiphany.

The Oriental Orthodox (other than the Armenians), the Eastern Orthodox, and the Eastern Catholics who follow the same traditions have a twelve-day interval between the two feasts. Christmas and Epiphany are celebrated by these churches on 25 December and 6 January using the Julian calendar, which correspond to 7 and 19 January using the Gregorian calendar. The Twelve Days, using the Gregorian calendar, end at sunset on 18 January.

Eastern Orthodoxy[edit]

For the Eastern Orthodox, both Christmas and Epiphany are among the Twelve Great Feasts that are only second to Easter in importance.[14]

The period between Christmas and Epiphany is fast-free.[14] During this period one celebration leads into another. The Nativity of Christ is a three-day celebration: the formal title of the first day (i. e. Christmas Eve) is «The Nativity According to the Flesh of our Lord, God and Saviour Jesus Christ», and celebrates not only the Nativity of Jesus, but also the Adoration of the Shepherds of Bethlehem and the arrival of the Magi; the second day is referred to as the «Synaxis of the Theotokos», and commemorates the role of the Virgin Mary in the Incarnation; the third day is known as the «Third Day of the Nativity», and is also the feast day of the Protodeacon and Protomartyr Saint Stephen. 29 December is the Orthodox Feast of the Holy Innocents. The Afterfeast of the Nativity (similar to the Western octave) continues until 31 December (that day is known as the Apodosis or «leave-taking» of the Nativity).

The Saturday following the Nativity is commemorated by special readings from the Epistle (1 Tim 6:11–16) and Gospel (Matt 12:15–21) during the Divine Liturgy. The Sunday after the Nativity has its own liturgical commemoration in honour of «The Righteous Ones: Joseph the Betrothed, David the King and James the Brother of the Lord».

Another of the more prominent festivals that are included among the Twelve Great Feasts is that of the Circumcision of Christ on 1 January.[14] On this same day is the feast day of Saint Basil the Great, and so the service celebrated on that day is the Divine Liturgy of Saint Basil.

On 2 January begins the Forefeast of the Theophany. The Eve of the Theophany on 5 January is a day of strict fasting, on which the devout will not eat anything until the first star is seen at night. This day is known as Paramony (Greek Παραμονή «Eve»), and follows the same general outline as Christmas Eve. That morning is the celebration of the Royal Hours and then the Divine Liturgy of Saint Basil combined with Vespers, at the conclusion of which is celebrated the Great Blessing of Waters, in commemoration of the Baptism of Jesus in the Jordan River. There are certain parallels between the hymns chanted on Paramony and those of Good Friday, to show that, according to Orthodox theology, the steps that Jesus took into the Jordan River were the first steps on the way to the Cross. That night the All-Night Vigil is served for the Feast of the Theophany.

Western Christianity[edit]

Within the Twelve Days of Christmas, there are celebrations both secular and religious.

Christmas Day, if it is considered to be part of the Twelve Days of Christmas and not as the day preceding the Twelve Days,[3] is celebrated by Christians as the liturgical feast of the Nativity of the Lord. It is a public holiday in many nations, including some where the majority of the population is not Christian. On this see the articles on Christmas and Christmas traditions.

26 December is «St. Stephen’s Day», a feast day in the Western Church. In the United Kingdom and its former colonies, it is also the secular holiday of Boxing Day. In some parts of Ireland it is denominated «Wren Day».

New Year’s Eve on 31 December is the feast of Pope St. Sylvester I and is known also as «Silvester». The transition that evening to the new year is an occasion for secular festivities in many nations, and in several languages is known as «St. Sylvester Night» («Notte di San Silvestro» in Italian, «Silvesternacht» in German, «Réveillon de la Saint-Sylvestre» in French, and «סילבסטר» in Hebrew).

New Year’s Day on 1 January is an occasion for further secular festivities or for rest from the celebrations of the night before. In the Roman Rite of the Roman Catholic Church, it is the Solemnity of Mary, Mother of God, liturgically celebrated on the Octave Day of Christmas. It has also been celebrated, and still is in some denominations, as the Feast of the Circumcision of Christ, because according to Jewish tradition He would have been circumcised on the eighth day after His Birth, inclusively counting the first day and last day. This day, or some day proximate to it, is also celebrated by the Roman Catholics as World Day of Peace.[15]

In many nations, e. g., the United States, the Solemnity of Epiphany is transferred to the first Sunday after 1 January, which can occur as early as 2 January. That solemnity, then, together with customary observances associated with it, usually occur within the Twelve Days of Christmas, even if these are considered to end on 5 January rather than 6 January.

Other Roman Catholic liturgical feasts on the General Roman Calendar that occur within the Octave of Christmas and therefore also within the Twelve Days of Christmas are the Feast of St. John, Apostle and Evangelist on 27 December; the Feast of the Holy Innocents on 28 December; Memorial of St. Thomas Becket, Bishop and Martyr on 29 December; and the Feast of the Holy Family of Jesus, Mary, and Joseph on the Sunday within the Octave of Christmas or, if there is no such Sunday, on 30 December. Outside the Octave, but within the Twelve Days of Christmas, there are the feast of Sts. Basil the Great and Gregory of Nazianzus on 2 January and the Memorial of the Holy Name of Jesus on 3 January.

Other saints are celebrated at a local level.

Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages[edit]

The Second Council of Tours of 567 noted that, in the area for which its bishops were responsible, the days between Christmas and Epiphany were, like the month of August, taken up entirely with saints’ days. Monks were therefore in principle not bound to fast on those days.[16] However, the first three days of the year were to be days of prayer and penance so that faithful Christians would refrain from participating in the idolatrous practices and debauchery associated with the new year celebrations. The Fourth Council of Toledo (633) ordered a strict fast on those days, on the model of the Lenten fast.[17][18]

England in the Middle Ages[edit]

In England in the Middle Ages, this period was one of continuous feasting and merrymaking, which climaxed on Twelfth Night, the traditional end of the Christmas season on 5 January (the last night before Ephiphany which started 6 January). William Shakespeare used it as the setting for one of his most famous stage plays, Twelfth Night. Often a Lord of Misrule was chosen to lead the Christmas revels.[19]

Some of these traditions were adapted from the older pagan customs, including the Roman Saturnalia and the Germanic Yuletide.[20] Some also have an echo in modern-day pantomime where traditionally authority is mocked and the principal male lead is played by a woman, while the leading older female character, or ‘Dame’, is played by a man.

Colonial North America[edit]

The early North American colonists brought their version of the Twelve Days over from England, and adapted them to their new country, adding their own variations over the years. For example, the modern-day Christmas wreath may have originated with these colonials.[21][22] A homemade wreath would be fashioned from local greenery and fruits, if available, were added. Making the wreaths was one of the traditions of Christmas Eve; they would remain hung on each home’s front door beginning on Christmas Night (first night of Christmas) through Twelfth Night or Epiphany morning. As was already the tradition in their native England, all decorations would be taken down by Epiphany morning and the remainder of the edibles would be consumed. A special cake, the king cake, was also baked then for Epiphany.

Modern Western customs[edit]

United Kingdom and Commonwealth[edit]

Many in the UK and other Commonwealth nations still celebrate some aspects of the Twelve Days of Christmas. Boxing Day, 26 December, is a national holiday in many Commonwealth nations. Victorian era stories by Charles Dickens, and others, particularly A Christmas Carol, hold key elements of the celebrations such as the consumption of plum pudding, roasted goose and wassail. These foods are consumed more at the beginning of the Twelve Days in the UK.

Twelfth Night is the last day for decorations to be taken down, and it is held to be bad luck to leave decorations up after this.[23] This is in contrast to the custom in Elizabethan England, when decorations were left up until Candlemas; this is still done in some other Western European countries such as Germany.

United States[edit]

In the United States, Christmas Day is a federal holiday which holds additional religious significance for Christians.[24]

The traditions of the Twelve Days of Christmas have been nearly forgotten in the United States. Contributing factors include the popularity of the stories of Charles Dickens in nineteenth-century America, with their emphasis on generous giving; introduction of secular traditions in the 19th and 20th centuries, e. g., the American Santa Claus; and increase in the popularity of secular New Year’s Eve parties. Presently, the commercial practice treats the Solemnity of Christmas, 25 December, the first day of Christmas, as the last day of the «Christmas» marketing season, as the numerous «after-Christmas sales» that commence on 26 December demonstrate. The commercial calendar has encouraged an erroneous assumption that the Twelve Days end on Christmas Day and must therefore begin on 14 December.[25]

Many American Christians still celebrate the traditional liturgical seasons of Advent and Christmas, especially Amish, Anglo-Catholics, Episcopalians, Lutherans, Mennonites, Methodists, Moravians, Nazarenes, Orthodox Christians, Presbyterians, and Roman Catholics. In Anglicanism, the designation of the «Twelve Days of Christmas» is used liturgically in the Episcopal Church in the US, having its own invitatory antiphon in the Book of Common Prayer for Matins.[4]

Christians who celebrate the Twelve Days may give gifts on each of them, with each of the Twelve Days representing a wish for a corresponding month of the new year. They may feast on traditional foods and otherwise celebrate the entire time through the morning of the Solemnity of Epiphany. Contemporary traditions include lighting a candle for each day, singing the verse of the corresponding day from the famous The Twelve Days of Christmas, and lighting a yule log on Christmas Eve and letting it burn some more on each of the twelve nights. For some, the Twelfth Night remains the night of the most festive parties and exchanges of gifts. Some households exchange gifts on the first (25 December) and last (5 January) days of the Twelve Days. As in former times, the Twelfth Night to the morning of Epiphany is the traditional time during which Christmas trees and decorations are removed.[citation needed]

References[edit]

- ^ Hatch, Jane M. (1978). The American Book of Days. Wilson. ISBN 9780824205935.

January 5th: Twelfth Night or Epiphany Eve. Twelfth Night, the last evening of the traditional Twelve Days of Christmas, has been observed with festive celebration ever since the Middle Ages.

- ^ Blackburn, Bonnie J. (1999). The Oxford companion to the year. Holford-Strevens, Leofranc. Oxford. ISBN 0-19-214231-3. OCLC 41834121.

- ^ a b Bratcher, Dennis (10 October 2014). «The Christmas Season». Christian Resource Institute. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

The Twelve Days of Christmas … in most of the Western Church are the twelve days from Christmas until the beginning of Epiphany (January 6th; the 12 days count from December 25th until January 5th). In some traditions, the first day of Christmas begins on the evening of December 25th with the following day considered the First Day of Christmas (December 26th). In these traditions, the twelve days begin December 26[th] and include Epiphany on January 6[th].

- ^ a b «The Book of Common Prayer» (PDF). New York: Church Publishing Incorporated. January 2007. p. 43. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

On the Twelve Days of Christmas Alleluia. Unto us a child is born: O come, let us adore Him. Alleluia.

- ^ Truscott, Jeffrey A. (2011). Worship. Armour Publishing. p. 103. ISBN 9789814305419.

As with the Easter cycle, churches today celebrate the Christmas cycle in different ways. Practically all Protestants observe Christmas itself, with services on 25 December or the evening before. Anglicans, Lutherans and other churches that use the ecumenical Revised Common Lectionary will likely observe the four Sundays of Advent, maintaining the ancient emphasis on the eschatological (First Sunday), ascetic (Second and Third Sundays), and scriptural/historical (Fourth Sunday). Besides Christmas Eve/Day, they will observe a 12-day season of Christmas from 25 December to 5 January.

- ^ Bl. Pope Paul VI, Universal Norms on the Liturgical Year, #33 (14 February 1969)

- ^ Fr. Francis X. Weiser. «Feast of the Nativity». Catholic Culture.

The Council of Tours (567) proclaimed the twelve days from Christmas to Epiphany as a sacred and festive season, and established the duty of Advent fasting in preparation for the feast. The Council of Braga (563) forbade fasting on Christmas Day.

- ^ Fox, Adam (19 December 2003). «‘Tis the season». The Guardian. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

Around the year 400 the feasts of St Stephen, John the Evangelist and the Holy Innocents were added on succeeding days, and in 567 the Council of Tours ratified the enduring 12-day cycle between the nativity and the epiphany.

- ^ Hynes, Mary Ellen (1993). Companion to the Calendar. Liturgy Training Publications. p. 8. ISBN 9781568540115.

In the year 567 the church council of Tours called the 13 days between December 25 and January 6 a festival season.

Martindale, Cyril Charles (1908). «Christmas». The Catholic Encyclopedia. New Advent. Retrieved 15 December 2014.The Second Council of Tours (can. xi, xvii) proclaims, in 566 or 567, the sanctity of the «twelve days» from Christmas to Epiphany, and the duty of Advent fast; …and that of Braga (563) forbids fasting on Christmas Day. Popular merry-making, however, so increased that the «Laws of King Cnut», fabricated c. 1110, order a fast from Christmas to Epiphany.

- ^ Bunson, Matthew (21 October 2007). «Origins of Christmas and Easter holidays». Eternal Word Television Network (EWTN). Retrieved 17 December 2014.

The Council of Tours (567) decreed the 12 days from Christmas to Epiphany to be sacred and especially joyous, thus setting the stage for the celebration of the Lord’s birth…

- ^ Hill, Christopher (2003). Holidays and Holy Nights: Celebrating Twelve Seasonal Festivals of the Christian Year. Quest Books. p. 91. ISBN 9780835608107.

This arrangement became an administrative problem for the Roman Empire as it tried to coordinate the solar Julian calendar with the lunar calendars of its provinces in the east. While the Romans could roughly match the months in the two systems, the four cardinal points of the solar year—the two equinoxes and solstices—still fell on different dates. By the time of the first century, the calendar date of the winter solstice in Egypt and Palestine was eleven to twelve days later than the date in Rome. As a result the Incarnation came to be celebrated on different days in different parts of the Empire. The Western Church, in its desire to be universal, eventually took them both—one became Christmas, one Epiphany—with a resulting twelve days in between. Over time this hiatus became invested with specific Christian meaning. The Church gradually filled these days with saints, some connected to the birth narratives in Gospels (Holy Innocents’ Day, December 28, in honor of the infants slaughtered by Herod; St. John the Evangelist, «the Beloved,» December 27; St. Stephen, the first Christian martyr, December 26; the Holy Family, December 31; the Virgin Mary, January 1). In 567, the Council of Tours declared the twelve days between Christmas and Epiphany to become one unified festal cycle.

Federer, William J. (6 January 2014). «On the 12th Day of Christmas». American Minute. Retrieved 25 December 2014.In 567 AD, the Council of Tours ended a dispute. Western Europe celebrated Christmas, 25 December, as the holiest day of the season… but Eastern Europe celebrated Epiphany, 6 January, recalling the Wise Men’s visit and Jesus’ baptism. It could not be decided which day was holier, so the Council made all 12 days from 25 December to 6 January «holy days» or «holidays,» These became known as «The Twelve Days of Christmas.»

- ^ Kirk Cameron, William Federer (6 November 2014). Praise the Lord. Trinity Broadcasting Network. Event occurs at 01:15:14. Archived from the original on 25 December 2014. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

Western Europe celebrated Christmas December 25 as the holiest day. Eastern Europe celebrated January 6 the Epiphany, the visit of the Wise Men, as the holiest day… and so they had this council and they decided to make all twelve days from December 25 to January 6 the Twelve Days of Christmas.

- ^ Kelly, Joseph F (2010). Joseph F. Kelly, The Feast of Christmas (Liturgical Press 2010 ISBN 978-0-81463932-0). ISBN 9780814639320.

- ^ a b c Kallistos Ware, The Orthodox Church

- ^ United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, «World Day of Peace»

- ^ Jean Hardouin; Philippe Labbé; Gabriel Cossart (1714). «Christmas». Acta Conciliorum et Epistolae Decretales (in Latin). Typographia Regia, Paris. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

De Decembri usque ad natale Domini, omni die ieiunent. Et quia inter natale Domini et epiphania omni die festivitates sunt, itemque prandebunt. Excipitur triduum illud, quo ad calcandam gentilium consuetudinem, patres nostri statuerunt privatas in Kalendariis Ianuarii fieri litanias, ut in ecclesiis psallatur, et hora octava in ipsis Kalendis Circumcisionis missa Deo propitio celebretur. (Translation: «In December until Christmas, they are to fast each day. Since between Christmas and Epiphany there are feasts on each day, they shall have a full meal, except during the three-day period on which, in order to tread Gentile customs down, our fathers established that private litanies for the Calends of January be chanted in the churches, and that on the Calends itself Mass of the Circumcision be celebrated at the eighth hour for God’s favour.»)

- ^ Christopher Labadie, «The Octave Day of Christmas: Historical Development and Modern Liturgical Practice» in Obsculta, vol. 7, issue 1, art. 8, p. 89

- ^ Adolf Adam, The Liturgical Year (Liturgical Press 1990 ISBN 978-0-81466047-8), p. 139

- ^ Frazer, James (1922). The Golden Bough. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 1-58734-083-6. Bartleby.com

- ^ Count, Earl (1997). 4,000 Years of Christmas. Ulysses Press. ISBN 1-56975-087-4.

- ^ New York Times, 27 December 1852: a report of holiday events mentions ‘a splendid wreath’ as being among the prizes won.

- ^ In 1953 a correspondence in the letter pages of The Times discussed whether Christmas wreaths were an alien importation or a version of the native evergreen ‘bunch’/’bough’/’garland’/’wassail bush’ traditionally displayed in England at Christmas. One correspondent described those she had seen placed on doors in country districts as either a plain bunch, a shape like a torque or open circle, and occasionally a more elaborate shape like a bell or interlaced circles. She felt the use of the words ‘Christmas wreath’ had ‘funereal associations’ for English people who would prefer to describe it as a ‘garland’. An advertisement in The Times of Friday, 26 December 1862; pg. 1; Issue 24439; col A, however, refers to an entertainment at Crystal Palace featuring ‘Extraordinary decorations, wreaths of evergreens …’, and in 1896 the special Christmas edition of The Girl’s Own Paper was titled ‘Our Christmas Wreath’:The Times Saturday, 19 December 1896; pg. 4; Issue 35078; col C. There is a custom of decorating graves at Christmas with somber wreaths of evergreen, which is still observed in parts of England, and this may have militated against the circle being the accepted shape for door decorations until the re-establishment of the tradition from America in the mid-to-late 20th century.

- ^ «Epiphany in United Kingdom». timeanddate.com. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- ^ Sirvaitis, Karen (1 August 2010). The European American Experience. Twenty-First Century Books. pp. 52. ISBN 9780761340881.

Christmas is a major holiday for Christians, although some non-Christians in the United States also mark the day as a holiday.

- ^ HumorMatters.com Twelve Days of Christmas (reprint of a magazine article). Retrieved 3 January 2011.

Sources[edit]

- «Christmas». Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 22 December 2005. Primarily subhead Popular Merrymaking under Liturgy and Custom.

- «The Twelve Days of Christmas». Catholic Culture. Retrieved 22 January 2012. Primarily subhead 12 Days of Christmas under Catholic and Culture.

- Bowler, Gerald (2000). The World Encyclopedia of Christmas. Toronto: M&S. ISBN 978-0-7710-1531-1. OCLC 44154451.

- Caulkins, Mary; Jennie Miller Helderman (2002). Christmas Trivia: 200 Fun & Fascinating Facts About Christmas. New York: Gramercy. ISBN 978-0-517-22070-2. OCLC 49627774.

- Collins, Ace; Clint Hansen (2003). Stories Behind the Great Traditions of Christmas. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-24880-4. OCLC 52311813.

- Evans, Martin Marix (2002). The Twelve Days of Christmas. White Plains, New York: Peter Pauper Press. ISBN 978-0-88088-776-2. OCLC 57044650.

- Wells, Robin Headlam (2005). Shakespeare’s Humanism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82438-5. OCLC 62132881.

- Hoh, John L. Jr. (2001). The Twelve Days of Christmas: A Carol Catechism. Vancouver: Suite 101 eBooks.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Twelve Days of Christmas | |

|---|---|

The Adoration of the Magi, Fresco at the Lower Church of the Basilica of San Francesco d’Assisi in Assisi, Italy. |

|

| Observed by | Christians |

| Type | Christian |

| Observances | Varies by denomination, culture, and nation |

| Date | 25 December – 5 January, inclusive |

| Frequency | annual |

| Related to | Christmas Day, Christmastide, Twelfth Night, Epiphany, and Epiphanytide |

The Twelve Days of Christmas, also known as Twelvetide, is a festive Christian season celebrating the Nativity of Jesus. In some Western ecclesiastical traditions, «Christmas Day» is considered the «First Day of Christmas» and the Twelve Days are 25 December to 5 January, inclusive,[1] with 6 January being a «thirteenth day» in some traditions and languages. However, 6 January is sometimes considered Twelfth Day/Twelfth Night with the Twelve Days «of» Christmas actually after Christmas Day from 26 December to 6 January.[2] For many Christian denominations—for example, the Anglican Communion and Lutheran Church—the Twelve Days are identical to Christmastide,[3][4][5] but for others, e.g. the Roman Catholic Church, Christmastide lasts longer than the Twelve Days of Christmas but the Christmas itself lasts one day on December 25.[6]

History[edit]

In 567, the Council of Tours «proclaimed the twelve days from Christmas to Epiphany (i.e. to just before midnight 5 January as Epiphany begins 6 January) as a sacred and festive season, and established the duty of Advent fasting in preparation for the feast.»[7][8][9][10] Christopher Hill, as well as William J. Federer, states that this was done in order to solve the «administrative problem for the Roman Empire as it tried to coordinate the solar Julian calendar with the lunar calendars of its provinces in the east.»[clarification needed][11][12]

Eastern Christianity[edit]

The Armenian Apostolic Church and Armenian Catholic Church celebrate the Birth and Baptism of Christ on the same day,[13] so that there is no distinction between a feast of Christmas and a feast of Epiphany.

The Oriental Orthodox (other than the Armenians), the Eastern Orthodox, and the Eastern Catholics who follow the same traditions have a twelve-day interval between the two feasts. Christmas and Epiphany are celebrated by these churches on 25 December and 6 January using the Julian calendar, which correspond to 7 and 19 January using the Gregorian calendar. The Twelve Days, using the Gregorian calendar, end at sunset on 18 January.

Eastern Orthodoxy[edit]

For the Eastern Orthodox, both Christmas and Epiphany are among the Twelve Great Feasts that are only second to Easter in importance.[14]

The period between Christmas and Epiphany is fast-free.[14] During this period one celebration leads into another. The Nativity of Christ is a three-day celebration: the formal title of the first day (i. e. Christmas Eve) is «The Nativity According to the Flesh of our Lord, God and Saviour Jesus Christ», and celebrates not only the Nativity of Jesus, but also the Adoration of the Shepherds of Bethlehem and the arrival of the Magi; the second day is referred to as the «Synaxis of the Theotokos», and commemorates the role of the Virgin Mary in the Incarnation; the third day is known as the «Third Day of the Nativity», and is also the feast day of the Protodeacon and Protomartyr Saint Stephen. 29 December is the Orthodox Feast of the Holy Innocents. The Afterfeast of the Nativity (similar to the Western octave) continues until 31 December (that day is known as the Apodosis or «leave-taking» of the Nativity).

The Saturday following the Nativity is commemorated by special readings from the Epistle (1 Tim 6:11–16) and Gospel (Matt 12:15–21) during the Divine Liturgy. The Sunday after the Nativity has its own liturgical commemoration in honour of «The Righteous Ones: Joseph the Betrothed, David the King and James the Brother of the Lord».

Another of the more prominent festivals that are included among the Twelve Great Feasts is that of the Circumcision of Christ on 1 January.[14] On this same day is the feast day of Saint Basil the Great, and so the service celebrated on that day is the Divine Liturgy of Saint Basil.

On 2 January begins the Forefeast of the Theophany. The Eve of the Theophany on 5 January is a day of strict fasting, on which the devout will not eat anything until the first star is seen at night. This day is known as Paramony (Greek Παραμονή «Eve»), and follows the same general outline as Christmas Eve. That morning is the celebration of the Royal Hours and then the Divine Liturgy of Saint Basil combined with Vespers, at the conclusion of which is celebrated the Great Blessing of Waters, in commemoration of the Baptism of Jesus in the Jordan River. There are certain parallels between the hymns chanted on Paramony and those of Good Friday, to show that, according to Orthodox theology, the steps that Jesus took into the Jordan River were the first steps on the way to the Cross. That night the All-Night Vigil is served for the Feast of the Theophany.

Western Christianity[edit]

Within the Twelve Days of Christmas, there are celebrations both secular and religious.

Christmas Day, if it is considered to be part of the Twelve Days of Christmas and not as the day preceding the Twelve Days,[3] is celebrated by Christians as the liturgical feast of the Nativity of the Lord. It is a public holiday in many nations, including some where the majority of the population is not Christian. On this see the articles on Christmas and Christmas traditions.

26 December is «St. Stephen’s Day», a feast day in the Western Church. In the United Kingdom and its former colonies, it is also the secular holiday of Boxing Day. In some parts of Ireland it is denominated «Wren Day».

New Year’s Eve on 31 December is the feast of Pope St. Sylvester I and is known also as «Silvester». The transition that evening to the new year is an occasion for secular festivities in many nations, and in several languages is known as «St. Sylvester Night» («Notte di San Silvestro» in Italian, «Silvesternacht» in German, «Réveillon de la Saint-Sylvestre» in French, and «סילבסטר» in Hebrew).

New Year’s Day on 1 January is an occasion for further secular festivities or for rest from the celebrations of the night before. In the Roman Rite of the Roman Catholic Church, it is the Solemnity of Mary, Mother of God, liturgically celebrated on the Octave Day of Christmas. It has also been celebrated, and still is in some denominations, as the Feast of the Circumcision of Christ, because according to Jewish tradition He would have been circumcised on the eighth day after His Birth, inclusively counting the first day and last day. This day, or some day proximate to it, is also celebrated by the Roman Catholics as World Day of Peace.[15]

In many nations, e. g., the United States, the Solemnity of Epiphany is transferred to the first Sunday after 1 January, which can occur as early as 2 January. That solemnity, then, together with customary observances associated with it, usually occur within the Twelve Days of Christmas, even if these are considered to end on 5 January rather than 6 January.

Other Roman Catholic liturgical feasts on the General Roman Calendar that occur within the Octave of Christmas and therefore also within the Twelve Days of Christmas are the Feast of St. John, Apostle and Evangelist on 27 December; the Feast of the Holy Innocents on 28 December; Memorial of St. Thomas Becket, Bishop and Martyr on 29 December; and the Feast of the Holy Family of Jesus, Mary, and Joseph on the Sunday within the Octave of Christmas or, if there is no such Sunday, on 30 December. Outside the Octave, but within the Twelve Days of Christmas, there are the feast of Sts. Basil the Great and Gregory of Nazianzus on 2 January and the Memorial of the Holy Name of Jesus on 3 January.

Other saints are celebrated at a local level.

Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages[edit]

The Second Council of Tours of 567 noted that, in the area for which its bishops were responsible, the days between Christmas and Epiphany were, like the month of August, taken up entirely with saints’ days. Monks were therefore in principle not bound to fast on those days.[16] However, the first three days of the year were to be days of prayer and penance so that faithful Christians would refrain from participating in the idolatrous practices and debauchery associated with the new year celebrations. The Fourth Council of Toledo (633) ordered a strict fast on those days, on the model of the Lenten fast.[17][18]

England in the Middle Ages[edit]

In England in the Middle Ages, this period was one of continuous feasting and merrymaking, which climaxed on Twelfth Night, the traditional end of the Christmas season on 5 January (the last night before Ephiphany which started 6 January). William Shakespeare used it as the setting for one of his most famous stage plays, Twelfth Night. Often a Lord of Misrule was chosen to lead the Christmas revels.[19]

Some of these traditions were adapted from the older pagan customs, including the Roman Saturnalia and the Germanic Yuletide.[20] Some also have an echo in modern-day pantomime where traditionally authority is mocked and the principal male lead is played by a woman, while the leading older female character, or ‘Dame’, is played by a man.

Colonial North America[edit]

The early North American colonists brought their version of the Twelve Days over from England, and adapted them to their new country, adding their own variations over the years. For example, the modern-day Christmas wreath may have originated with these colonials.[21][22] A homemade wreath would be fashioned from local greenery and fruits, if available, were added. Making the wreaths was one of the traditions of Christmas Eve; they would remain hung on each home’s front door beginning on Christmas Night (first night of Christmas) through Twelfth Night or Epiphany morning. As was already the tradition in their native England, all decorations would be taken down by Epiphany morning and the remainder of the edibles would be consumed. A special cake, the king cake, was also baked then for Epiphany.

Modern Western customs[edit]

United Kingdom and Commonwealth[edit]

Many in the UK and other Commonwealth nations still celebrate some aspects of the Twelve Days of Christmas. Boxing Day, 26 December, is a national holiday in many Commonwealth nations. Victorian era stories by Charles Dickens, and others, particularly A Christmas Carol, hold key elements of the celebrations such as the consumption of plum pudding, roasted goose and wassail. These foods are consumed more at the beginning of the Twelve Days in the UK.

Twelfth Night is the last day for decorations to be taken down, and it is held to be bad luck to leave decorations up after this.[23] This is in contrast to the custom in Elizabethan England, when decorations were left up until Candlemas; this is still done in some other Western European countries such as Germany.

United States[edit]

In the United States, Christmas Day is a federal holiday which holds additional religious significance for Christians.[24]

The traditions of the Twelve Days of Christmas have been nearly forgotten in the United States. Contributing factors include the popularity of the stories of Charles Dickens in nineteenth-century America, with their emphasis on generous giving; introduction of secular traditions in the 19th and 20th centuries, e. g., the American Santa Claus; and increase in the popularity of secular New Year’s Eve parties. Presently, the commercial practice treats the Solemnity of Christmas, 25 December, the first day of Christmas, as the last day of the «Christmas» marketing season, as the numerous «after-Christmas sales» that commence on 26 December demonstrate. The commercial calendar has encouraged an erroneous assumption that the Twelve Days end on Christmas Day and must therefore begin on 14 December.[25]

Many American Christians still celebrate the traditional liturgical seasons of Advent and Christmas, especially Amish, Anglo-Catholics, Episcopalians, Lutherans, Mennonites, Methodists, Moravians, Nazarenes, Orthodox Christians, Presbyterians, and Roman Catholics. In Anglicanism, the designation of the «Twelve Days of Christmas» is used liturgically in the Episcopal Church in the US, having its own invitatory antiphon in the Book of Common Prayer for Matins.[4]

Christians who celebrate the Twelve Days may give gifts on each of them, with each of the Twelve Days representing a wish for a corresponding month of the new year. They may feast on traditional foods and otherwise celebrate the entire time through the morning of the Solemnity of Epiphany. Contemporary traditions include lighting a candle for each day, singing the verse of the corresponding day from the famous The Twelve Days of Christmas, and lighting a yule log on Christmas Eve and letting it burn some more on each of the twelve nights. For some, the Twelfth Night remains the night of the most festive parties and exchanges of gifts. Some households exchange gifts on the first (25 December) and last (5 January) days of the Twelve Days. As in former times, the Twelfth Night to the morning of Epiphany is the traditional time during which Christmas trees and decorations are removed.[citation needed]

References[edit]

- ^ Hatch, Jane M. (1978). The American Book of Days. Wilson. ISBN 9780824205935.

January 5th: Twelfth Night or Epiphany Eve. Twelfth Night, the last evening of the traditional Twelve Days of Christmas, has been observed with festive celebration ever since the Middle Ages.

- ^ Blackburn, Bonnie J. (1999). The Oxford companion to the year. Holford-Strevens, Leofranc. Oxford. ISBN 0-19-214231-3. OCLC 41834121.

- ^ a b Bratcher, Dennis (10 October 2014). «The Christmas Season». Christian Resource Institute. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

The Twelve Days of Christmas … in most of the Western Church are the twelve days from Christmas until the beginning of Epiphany (January 6th; the 12 days count from December 25th until January 5th). In some traditions, the first day of Christmas begins on the evening of December 25th with the following day considered the First Day of Christmas (December 26th). In these traditions, the twelve days begin December 26[th] and include Epiphany on January 6[th].

- ^ a b «The Book of Common Prayer» (PDF). New York: Church Publishing Incorporated. January 2007. p. 43. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

On the Twelve Days of Christmas Alleluia. Unto us a child is born: O come, let us adore Him. Alleluia.

- ^ Truscott, Jeffrey A. (2011). Worship. Armour Publishing. p. 103. ISBN 9789814305419.

As with the Easter cycle, churches today celebrate the Christmas cycle in different ways. Practically all Protestants observe Christmas itself, with services on 25 December or the evening before. Anglicans, Lutherans and other churches that use the ecumenical Revised Common Lectionary will likely observe the four Sundays of Advent, maintaining the ancient emphasis on the eschatological (First Sunday), ascetic (Second and Third Sundays), and scriptural/historical (Fourth Sunday). Besides Christmas Eve/Day, they will observe a 12-day season of Christmas from 25 December to 5 January.

- ^ Bl. Pope Paul VI, Universal Norms on the Liturgical Year, #33 (14 February 1969)

- ^ Fr. Francis X. Weiser. «Feast of the Nativity». Catholic Culture.

The Council of Tours (567) proclaimed the twelve days from Christmas to Epiphany as a sacred and festive season, and established the duty of Advent fasting in preparation for the feast. The Council of Braga (563) forbade fasting on Christmas Day.

- ^ Fox, Adam (19 December 2003). «‘Tis the season». The Guardian. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

Around the year 400 the feasts of St Stephen, John the Evangelist and the Holy Innocents were added on succeeding days, and in 567 the Council of Tours ratified the enduring 12-day cycle between the nativity and the epiphany.

- ^ Hynes, Mary Ellen (1993). Companion to the Calendar. Liturgy Training Publications. p. 8. ISBN 9781568540115.

In the year 567 the church council of Tours called the 13 days between December 25 and January 6 a festival season.

Martindale, Cyril Charles (1908). «Christmas». The Catholic Encyclopedia. New Advent. Retrieved 15 December 2014.The Second Council of Tours (can. xi, xvii) proclaims, in 566 or 567, the sanctity of the «twelve days» from Christmas to Epiphany, and the duty of Advent fast; …and that of Braga (563) forbids fasting on Christmas Day. Popular merry-making, however, so increased that the «Laws of King Cnut», fabricated c. 1110, order a fast from Christmas to Epiphany.

- ^ Bunson, Matthew (21 October 2007). «Origins of Christmas and Easter holidays». Eternal Word Television Network (EWTN). Retrieved 17 December 2014.

The Council of Tours (567) decreed the 12 days from Christmas to Epiphany to be sacred and especially joyous, thus setting the stage for the celebration of the Lord’s birth…

- ^ Hill, Christopher (2003). Holidays and Holy Nights: Celebrating Twelve Seasonal Festivals of the Christian Year. Quest Books. p. 91. ISBN 9780835608107.

This arrangement became an administrative problem for the Roman Empire as it tried to coordinate the solar Julian calendar with the lunar calendars of its provinces in the east. While the Romans could roughly match the months in the two systems, the four cardinal points of the solar year—the two equinoxes and solstices—still fell on different dates. By the time of the first century, the calendar date of the winter solstice in Egypt and Palestine was eleven to twelve days later than the date in Rome. As a result the Incarnation came to be celebrated on different days in different parts of the Empire. The Western Church, in its desire to be universal, eventually took them both—one became Christmas, one Epiphany—with a resulting twelve days in between. Over time this hiatus became invested with specific Christian meaning. The Church gradually filled these days with saints, some connected to the birth narratives in Gospels (Holy Innocents’ Day, December 28, in honor of the infants slaughtered by Herod; St. John the Evangelist, «the Beloved,» December 27; St. Stephen, the first Christian martyr, December 26; the Holy Family, December 31; the Virgin Mary, January 1). In 567, the Council of Tours declared the twelve days between Christmas and Epiphany to become one unified festal cycle.

Federer, William J. (6 January 2014). «On the 12th Day of Christmas». American Minute. Retrieved 25 December 2014.In 567 AD, the Council of Tours ended a dispute. Western Europe celebrated Christmas, 25 December, as the holiest day of the season… but Eastern Europe celebrated Epiphany, 6 January, recalling the Wise Men’s visit and Jesus’ baptism. It could not be decided which day was holier, so the Council made all 12 days from 25 December to 6 January «holy days» or «holidays,» These became known as «The Twelve Days of Christmas.»

- ^ Kirk Cameron, William Federer (6 November 2014). Praise the Lord. Trinity Broadcasting Network. Event occurs at 01:15:14. Archived from the original on 25 December 2014. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

Western Europe celebrated Christmas December 25 as the holiest day. Eastern Europe celebrated January 6 the Epiphany, the visit of the Wise Men, as the holiest day… and so they had this council and they decided to make all twelve days from December 25 to January 6 the Twelve Days of Christmas.

- ^ Kelly, Joseph F (2010). Joseph F. Kelly, The Feast of Christmas (Liturgical Press 2010 ISBN 978-0-81463932-0). ISBN 9780814639320.

- ^ a b c Kallistos Ware, The Orthodox Church

- ^ United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, «World Day of Peace»

- ^ Jean Hardouin; Philippe Labbé; Gabriel Cossart (1714). «Christmas». Acta Conciliorum et Epistolae Decretales (in Latin). Typographia Regia, Paris. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

De Decembri usque ad natale Domini, omni die ieiunent. Et quia inter natale Domini et epiphania omni die festivitates sunt, itemque prandebunt. Excipitur triduum illud, quo ad calcandam gentilium consuetudinem, patres nostri statuerunt privatas in Kalendariis Ianuarii fieri litanias, ut in ecclesiis psallatur, et hora octava in ipsis Kalendis Circumcisionis missa Deo propitio celebretur. (Translation: «In December until Christmas, they are to fast each day. Since between Christmas and Epiphany there are feasts on each day, they shall have a full meal, except during the three-day period on which, in order to tread Gentile customs down, our fathers established that private litanies for the Calends of January be chanted in the churches, and that on the Calends itself Mass of the Circumcision be celebrated at the eighth hour for God’s favour.»)

- ^ Christopher Labadie, «The Octave Day of Christmas: Historical Development and Modern Liturgical Practice» in Obsculta, vol. 7, issue 1, art. 8, p. 89

- ^ Adolf Adam, The Liturgical Year (Liturgical Press 1990 ISBN 978-0-81466047-8), p. 139

- ^ Frazer, James (1922). The Golden Bough. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 1-58734-083-6. Bartleby.com

- ^ Count, Earl (1997). 4,000 Years of Christmas. Ulysses Press. ISBN 1-56975-087-4.

- ^ New York Times, 27 December 1852: a report of holiday events mentions ‘a splendid wreath’ as being among the prizes won.

- ^ In 1953 a correspondence in the letter pages of The Times discussed whether Christmas wreaths were an alien importation or a version of the native evergreen ‘bunch’/’bough’/’garland’/’wassail bush’ traditionally displayed in England at Christmas. One correspondent described those she had seen placed on doors in country districts as either a plain bunch, a shape like a torque or open circle, and occasionally a more elaborate shape like a bell or interlaced circles. She felt the use of the words ‘Christmas wreath’ had ‘funereal associations’ for English people who would prefer to describe it as a ‘garland’. An advertisement in The Times of Friday, 26 December 1862; pg. 1; Issue 24439; col A, however, refers to an entertainment at Crystal Palace featuring ‘Extraordinary decorations, wreaths of evergreens …’, and in 1896 the special Christmas edition of The Girl’s Own Paper was titled ‘Our Christmas Wreath’:The Times Saturday, 19 December 1896; pg. 4; Issue 35078; col C. There is a custom of decorating graves at Christmas with somber wreaths of evergreen, which is still observed in parts of England, and this may have militated against the circle being the accepted shape for door decorations until the re-establishment of the tradition from America in the mid-to-late 20th century.

- ^ «Epiphany in United Kingdom». timeanddate.com. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- ^ Sirvaitis, Karen (1 August 2010). The European American Experience. Twenty-First Century Books. pp. 52. ISBN 9780761340881.

Christmas is a major holiday for Christians, although some non-Christians in the United States also mark the day as a holiday.

- ^ HumorMatters.com Twelve Days of Christmas (reprint of a magazine article). Retrieved 3 January 2011.

Sources[edit]