Праздник праздников и Торжество торжеств, Светлое Христово Воскресенье — Святая Пасха Христова

Пасха в 2023 году — 16 апреля!

Воскресение Христово (Пасха) — это самый главный христианский праздник, установленный в воспоминание Воскресения Исуса Христа из мертвых. От даты Пасхи зависит и Устав церковной службы (с этого дня начинается отсчет «столпов» осмогласия), и окончание самого длинного и строгого Великого поста (разговенье) и многие другие православные праздники. Даже для людей, далеких от религии, святая Пасха ассоциируется с ночной торжественной службой, крестным ходом и куличами, крашеными яйцами и колокольным звоном. А в чем же духовный смысл праздника Пасхи и каковы его традиции? — Об этом в статье ниже.

Содержание

- Пасха Христова. Сколько дней празднуется?

- Событие праздника Пасхи: отрывок из Евангелия

- Празднование Пасхи в истории. Почему воскресенье называется воскресеньем?

- Какого числа Пасха у православных?

- Как рассчитать дату Пасхи?

- Православная пасхальная служба

- Традиции празднования Пасхи у старообрядцев

- Воскресение Христово. Иконы

- Храмы Воскресения Христова

- Старообрядческие храмы Воскресения Христова

- Христианская Пасха и Песах у иудеев (Еврейская Пасха) в 2021 году

- Новопасхалисты и их учение

Пасха Христова. Сколько дней празднуется?

Пасха — самый главный и торжественный христианский праздник. Он совершается каждый год в разное время и относится к подвижным праздникам. От дня Пасхи зависят и прочие подвижные праздники, такие как: Вербное воскресенье, Вознесение Господне, Праздник святой Троицы (Пятидесятница) и другие. Празднование Пасхи — самое продолжительное: 40 дней верующие приветствуют друг друга словами «Христос воскресе!» — «Воистину воскресе!». День Светлого Христова Воскресения для христиан — это время особого торжества и духовной радости, когда верующие собираются на службы славословить воскресшего Христа, а вся Пасхальная седмица празднуется «как един день». Церковная служба всю неделю почти полностью повторяет ночное пасхальное богослужение.

Событие праздника Пасхи: отрывок из Евангелия

Христианский праздник Пасхи — это торжественное воспоминание Воскресения Господа на третий день после Его страданий и смерти. Сам момент Воскресения не описан в Евангелии, ведь никто не видел, как это произошло. Снятие со Креста и погребение Господа было совершено вечером в пятницу. Поскольку суббота была у иудеев днем покоя, женщины, сопровождавшие Господа и учеников из Галилеи, бывшие свидетелями Его страданий и смерти, пришли ко Гробу Господню только через день, на рассвете того дня, который мы теперь называем воскресным. Они несли благовония, которые по обычаю того времени возливали на тело умершего человека.

По прошествии же субботы, на рассвете первого дня недели, пришла Мария Магдалина и другая Мария посмотреть гроб. И вот, сделалось великое землетрясение, ибо Ангел Господень, сошедший с небес, приступив, отвалил камень от двери гроба и сидел на нем; вид его был, как молния, и одежда его бела, как снег; устрашившись его, стерегущие пришли в трепет и стали, как мертвые; Ангел же, обратив речь к женщинам, сказал: не бойтесь, ибо знаю, что вы ищете Исуса распятого; Его нет здесь — Он воскрес, как сказал. Подойдите, посмотрите место, где лежал Господь, и пойдите скорее, скажите ученикам Его, что Он воскрес из мертвых и предваряет вас в Галилее; там Его увидите. Вот, я сказал вам.

И, выйдя поспешно из гроба, они со страхом и радостью великою побежали возвестить ученикам Его. Когда же шли они возвестить ученикам Его, и се Исус встретил их и сказал: радуйтесь! И они, приступив, ухватились за ноги Его и поклонились Ему. Тогда говорит им Исус: не бойтесь; пойдите, возвестите братьям Моим, чтобы шли в Галилею, и там они увидят Меня» (Мф. 28, 1–10).

Библиотека Русской веры

Описание Исуса Христа историком I века Иосифом Флавием. Лицевой летописный свод (Всемирная история, книга 5) →

Читать онлайн

Празднование Пасхи в истории. Почему воскресенье называется воскресеньем?

От христианского праздника Пасхи происходит и современное название дня недели — воскресенье. Каждое воскресенье недели на протяжении всего года христиане особенно отмечают молитвой и торжественной службой в храме. Воскресенье еще называют «малой Пасхой». Воскресенье называется воскресеньем в честь воскресшего в третий день после распятия Исуса Христа. И хотя Воскресение Господне христиане вспоминают еженедельно, но особенно торжественно отмечается это событие один раз в году — на праздник Пасхи.

В первые века христианства существовало разделение на Пасху крестную и Пасху воскресную. Упоминания об этом содержатся в творениях ранних отцов Церкви: послании святителя Иринея Лионского (ок. 130–202) к римскому епископу Виктору, «Слове о Пасхе» святителя Мелитона Сардийского (нач. II в. — ок. 190), творениях святителя Климента Александрийского (ок. 150 — ок. 215) и Ипполита Папы Римского (ок. 170 — ок. 235). Пасха крестная — воспоминания страданий и смерти Спасителя отмечалась особым постом и совпадала с иудейской Пасхой в память о том, что Господь был распят во время этого ветхозаветного праздника. Первые христиане молились и строго постились до самой Пасхи воскресной — радостного воспоминания Воскресения Христова.

В настоящее время нет деления на Пасху крестную и воскресную, хотя содержание сохранилось в богослужебном Уставе: строгие и скорбные службы Великих Четвертка, Пятка и Субботы завершаются радостным и ликующим Пасхальным богослужением. Собственно и сама Пасхальная ночная служба начинается скорбной полунощницей, на которой читается канон Великой Субботы. В это время посреди храма еще стоит аналой с Плащаницей — шитой или писанной иконой, изображающей положение Господа во гроб.

Какого числа Пасха у православных?

Общины первых христиан праздновали Пасху в разное время. Одни вместе с иудеями, как пишет блаженный Иероним, другие — в первое воскресенье после иудеев, поскольку Христос был распят в день Песаха и воскрес наутро после субботы. Постепенно различие пасхальных традиций поместных Церквей становилось все более заметным, возник так называемый «пасхальный спор» между восточными и западными христианскими общинами, возникла угроза единству Церкви. На Первом Вселенском Соборе, созванном императором Константином в 325 году в Никее, рассматривался вопрос о едином для всех праздновании Пасхи. По словам церковного историка Евсевия Кесарийского, все епископы не только приняли Символ Веры, но и условились праздновать Пасху всем в один день:

Для согласного исповедания Веры спасительное празднование Пасхи надлежало совершать всем в одно и то же время. Поэтому сделано было общее постановление и утверждено подписью каждого из присутствовавших. Окончив эти дела, василевс (Константин Великий) сказал, что он одержал теперь вторую победу над врагом Церкви, и потому совершил победное посвященное празднество Богу.

С того времени все поместные Церкви стали праздновать Пасху в первое воскресенье после первого полнолуния, наступившего после весеннего равноденствия. Если же в это воскресенье выпадает Пасха иудейская, то христиане переносят празднование на следующее воскресенье, поскольку еще в правилах святых Апостолов, согласно 7-му правилу, запрещено христианам праздновать Пасху вместе с иудеями.

Как рассчитать дату Пасхи?

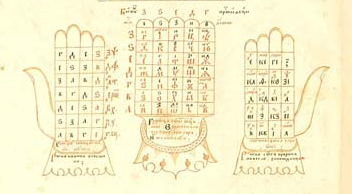

Для расчета Пасхи нужно знать не только солнечный (равноденствие), но и лунный календарь (полнолуние). Поскольку лучшие знатоки лунного и солнечного календаря жили в то время в Египте, честь вычисления православной пасхалии была предоставлена Александрийскому епископу. Он должен был ежегодно извещать все поместные Церкви о дне Пасхи. Со временем была создана Пасхалия на 532 года. Она основана на периодичности юлианского календаря, в котором календарные показатели расчета Пасхи — круг Солнца (28 лет) и круг Луны (19 лет) — повторяются через 532 года. Этот период называется «великим индиктионом». Начало первого «великого индиктиона» совпадает с началом эры «от сотворения мира». Текущий, 15 великий индиктион, начался в 1941 году. На Руси пасхальные таблицы включали в состав богослужебных книг, например, Следованную Псалтырь. Известно также несколько рукописей XVII–XVII вв. под названием «Великий миротворный круг». В них содержатся не только Пасхалия на 532 года, но и таблицы для расчета даты Пасхи по руке, так называемая Пятиперстная Пасхалия или «рука Дамаскина».

Стоит отметить, что в старообрядчестве до настоящего времени сохранились знания, как рассчитать по руке дату Пасхи, любого подвижного праздника, умение определить, в какой день недели приходится тот или иной праздник, продолжительности Петрова поста и другие важные сведения, необходимые для совершения богослужения.

Православная пасхальная служба

Всю Страстную седмицу, предшествующую Пасхе, каждый из дней которой называется Великим, православные христиане совершают службы и вспоминают Страсти Христовы, последние дни земной жизни Спасителя, Его страдания, распятие, смерть на Кресте, погребение, схождение во ад и Воскресение. Для христиан это особо почитаемая неделя, время особо строгого поста, подготовки к встрече главного христианского праздника.

Перед началом праздничной службы в храме читаются Деяния апостолов. Пасхальная служба, как и в древности, совершается ночью. Богослужение начинается за два часа до полуночи Воскресной полунощницей, во время которой читают канон Великой субботы «Волною морскою». На 9-й песни канона, когда поется ирмос «Не рыдай Мене, Мати», после каждения, Плащаница уносится в алтарь. У старообрядцев-безпоповцев после третьей песни канона и седальна читается слово Епифания Кипрского «Что се безмолвие».

После полунощницы начинается подготовка к Крестному ходу. Священнослужители в блестящих ризах, с крестом, Евангелием и иконами выходят из храма, за ними следуют молящиеся с горящими свечами; трижды обходят храм посолонь (по солнцу, по часовой стрелке) с пением стихеры: «Воскресение Твое, Христе Спасе, Ангели поют на небеси, и нас на земли сподоби чистыми сердцы Тебе славити». Этот крестный ход напоминает шествие мироносиц глубоким утром ко гробу, чтобы помазать Тело Исуса Христа. Крестный ход останавливается у западных дверей, которые бывают затворены: это напоминает снова мироносиц, получивших первую весть о воскресении Господа у дверей гроба. «Кто отвалит нам камень от гроба?» — недоумевают они.

Священник, покадив иконы и присутствующих, начинает светлую утреню возгласом: «Слава Святей, и Единосущней, и Животворящей, и Неразделимей Троице». Храм освещается множеством светильников. Священно- и церковнослужители поют трижды тропарь празднику:

Хrт0съ воскрeсе и3зъ мeртвыхъ смeртію на смeрть наступи2 и3 грHбнымъ жив0тъ даровA.

После этого тропарь многократно повторяют певчие при возглашении священником стихов: «Да воскреснет Бог» и прочих. Затем священнослужитель с крестом в руках, изображая Ангела, отвалившего камень от дверей гроба, открывает затворенные двери храма и все верующие входят в храм. Далее, после великой ектении, поется торжественным и ликующим напевом пасхальный канон: «Воскресения день», составленный св. Иоанном Дамаскиным. Тропари пасхального канона не читаются, а поются с припевом: «Христос воскресе из мертвых». Во время пения канона священник, держа в руках крест, на каждой песни кадит святые иконы и народ, приветствуя его радостным восклицанием: «Христос воскресе». Народ отвечает: «Воистину воскресе». Многократный выход священника с каждением и приветствием «Христос воскресе» изображает многократные явления Господа своим ученикам и радость их при виде Его. После каждой песни канона произносится малая ектения. По окончании канона поется следующий утренний светилен:

Пл0тію ўснyвъ ћкw мeртвъ, цRь и3 гDь, триднeвенъ воскRсе, и3 ґдaма воздви1гъ и3з8 тли2, и3 ўпраздни1въ смeрть. пaсха нетлёніz, ми1ру спасeніе.

(Перевод: Царь и Господь! Уснув плотью, как мертвец, Ты воскрес тридневный, воздвигнув от погибели Адама и уничтожив смерть; Ты — пасха безсмертия, спасение мира).

Затем читаются хвалитные псалмы и поются стихеры на хвалитех. К ним присоединяются стихеры Пасхи с припевом: «Да воскреснет Бог и разыдутся врази Его». После этого, при пении тропаря «Христос воскресе», верующие дают друг другу братское лобзание, т.е. «христосуются», с радостным приветствием: «Христос воскресе» — «Воистину воскресе». После пения пасхальных стихер бывает чтение слова св. Иоанна Златоустого: «Аще кто благочестив и боголюбив». Затем произносятся ектении и следует отпуст утрени, который священник совершает с крестом в руке, возглашая: «Христос воскресе». Далее поются пасхальные часы, которые состоят из пасхальных песнопений. По окончании пасхальных часов совершается пасхальная литургия. Вместо Трисвятого на пасхальной литургии поется «Елицы во Христа крестистеся, во Христа облекостеся. Аллилуиа». Апостол читается из Деяний св. апостолов (Деян. 1, 1-8), Евангелие читается от Иоанна (1, 1-17), в котором говорится о воплощении Сына Божия Исуса Христа, называемого в Евангелии «Словом». В некоторых приходах староверов-поповцев есть интересный обычай — на пасхальной Литургии читать Евангелие одновременно несколькими священнослужителями и даже на нескольких языках (повторяя каждый стих Евангелия несколько раз). Так, в некоторых липованских приходах читают на церковно-славянском и румынском, в России — на церковно-славянском и греческом. Некоторые прихожане Покровского собора на Рогожском вспоминают, что владыка Геронтий (Лакомкин) на Пасху читал Евангелие по-гречески.

Отличительная особенность пасхальной службы: она вся поется. Храмы в это время ярко освещены свечами, которые молящиеся держат в руках и ставят перед иконами. Благословением после литургии «брашен», т.е. сыра, мяса и яиц, дается верующим разрешение от поста.

Вечером совершается пасхальная вечерня. Особенность ее следующая. Настоятель облачается во все священные одежды и после вечернего входа с Евангелием читает на престоле Евангелие, повествующее о явлении Господа Исуса Христа Апостолам вечером в день Своего воскресения из мертвых (Ин. XX, 19-23). Богослужение первого дня св. Пасхи повторяется в течение всей пасхальной недели, за исключением чтения Евангелия на вечерни. В течение 40 дней, до праздника Вознесения Господня, поются за богослужением пасхальные тропари, стихеры и каноны. Молитва Св. Духу: «Царю Небесный» не читается и не поется до праздника Св. Троицы.

Кондак празднику:

Ѓще и3 в0 гроб сни1де без8смeртне, но ѓдову разруши1въ си1лу, и3 воскрeсе ћкw побэди1тель хrтE б9е. женaмъ мmрwн0сицамъ рaдость провэщaвъ, и3 свои1мъ ґпcлwмъ ми1ръ даровA, и4же пaдшимъ подаS воскrніе.

(Перевод: Хотя Ты, Бессмертный, и во гроб сошел, но уничтожил могущество ада и, как Победитель, воскрес, Христе Боже, женам-мироносицам сказав: «Радуйтесь». апостолам своим преподал мир, падшим подаешь воскресение).

В приходных и исходных поклонах вместо «Досто́йно есть» (вплоть до отдания Пасхи) читается ирмос девятой песни пасхального канона:

Свэти1сz свэти1сz н0выи їєrли1ме, слaва бо гDнz на тебЁ восіS. ликyй нн7э и3 весели1сz сіHне, тh же чcтаz красyйсz бцdе, њ востaніи ржcтвA твоегw2 (поклон земной).

(Перевод: Осветись, осветись (paдостью) новый Иерусалим; ибо слава Господня возсияла над тобою; торжествуй ныне и веселись Сион: и Ты, Богородица, радуйся о воскресении Рожденного Тобою).

К сожалению, сегодня не всякий человек может попасть в старообрядческий храм на Пасхальную службу. Во многих регионах нет старообрядческих храмов, в других они настолько удалены, что добраться до них чрезвычайно сложно. Поэтому в разделе Библиотека размещено последование Пасхального Богослужения по двум Уставам. Пасхальное Богослужение по сокращенному Уставу включает в себя последовательно Светлую Утреню, Канон Пасхи, Пасхальные часы, Обедницу (гражданским шрифтом). Также предлагаем подробное последование службы на Святую Пасху мирским чином (на церковнославянском языке в формате pdf), которое широко используется в безпоповских общинах за отсутствием священства.

Библиотека Русской веры

Богослужение на святую Пасху →

Читать онлайн

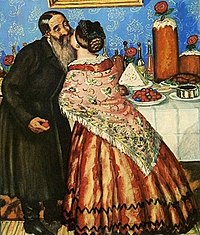

Традиции празднования Пасхи у старообрядцев

У старообрядцев всех согласий — и поповцев, и безпоповцев традиции празднования Светлого Христова Воскресения во многом общие. Разговение на Святую Пасху староверы начинают за трапезой в кругу семьи после храмового богослужения. Во многих общинах есть и общая церковная трапеза, за которой собирается много верующих. В день Воскресения Христова на стол ставят особые блюда, которые готовят только раз в году: пасхальный кулич, творожную пасху, крашеные яйца. Кроме особенных пасхальных блюд готовят множество традиционных лакомств русской кухни. В начале Пасхальной трапезы принято вкушать освященную в храме пищу, затем уже все остальные блюда.

На Пасху принято христосоваться — поздравлять друг друга с великим праздником и обмениваться крашеными яйцами, как символом жизни, трижды целуя друг друга. Подробнее о пасхальном целовании можно прочитать в комментарии о. Ивана Курбацкого «Как правильно христосоваться: целовать нужно друг друга один раз или трижды?»

Окрашенное в красный цвет луковой шелухой яйцо раньше называли крашенка, расписное — писанка, а деревянные пасхальные яйца — яйчата. Яйцо красного цвета знаменует для людей возрождение кровью Христовой.

Другие цвета и узоры, которыми расписывают яйца, — это нововведение, которое во многих безпоповских общинах не приветствуется, как и термонаклейки с изображением лика Христа, Богородицы, изображениями храмов и надписями. Вся эта «полиграфия» обычно широко представлена на прилавках магазинов в предпасхальные недели, однако мало кто задумывается о дальнейшей судьбе такой термонаклейки — после того, как ее счистят с пасхального яйца, она вместе с изображением Исуса Христа или Богородицы отправляется прямиком в мусорное ведро.

Внутри безпоповских согласий существует ряд отличий празднования Пасхи. Так, в некоторых безпоповских общинах Сибири куличи вообще не пекут и, соответственно, не освящают, считая это еврейским обычаем. В других общинах нет переодевания, смены темных одежд и платков на светлые, прихожане остаются в той же христианской одежде, что и пришли на богослужение. Общим в пасхальных традициях староверов всех согласий является, безусловно, отношение к работе во время Светлой седмицы. В канун праздника или воскресения христиане работают только до половины дня, предшествующего празднику, а во всю Пасхальную седмицу работать для староверов большой грех. Это время духовной радости, время торжественной молитвы и прославления воскресшего Христа. В отличие от старообрядцев-поповцев, в некоторых безпоповских согласиях нет обычая обхода наставником домов прихожан с Христославлением, однако каждый прихожанин, по желанию, безусловно, может пригласить наставника для пения пасхальных стихер и праздничной трапезы.

Праздник Светлой Пасхи — самый любимый Праздник еще с детства, он всегда радостный, особенно теплый и торжественный! Особенно много радости он приносит детям, а каждый верующий старается подать пасхальное яйцо, кулич или сладости, в первую очередь именно ребенку.

На Светлой неделе в некоторых безпоповских общинах до сих пор сохранилась древняя забава для малышей, к которой с нескрываемой радостью присоединяются и взрослые — катание крашеных (неосвященных) яиц. Суть игры такова: каждый игрок катит своё яйцо по специальной деревянной дорожке — желобу, и если укатившееся яйцо попадет в чье-то другое яйцо, то игрок забирает его себе как приз. Недалеко от желоба обычно раскладывают еще и подарки-сувениры. В старину такие соревнования могли длиться по несколько часов! А «счастливчики» возвращались домой с богатым «урожаем» яиц.

Для всех староверов, независимо от согласия, Пасха — это Праздник праздников и Торжество торжеств, это победа добра над злом, света над тьмой, это великое торжество, ангелов и архангелов вечный праздник, жизнь безсмертная для всего мира, нетленное небесное блаженство для людей. Искупительная жертва Господа Бога и Спаса нашего Исуса Христа, пролитая Им на Честном Кресте кровь избавила человека от страшной власти греха и смерти. Да будет «Пасха нова святая, Пасха таинственная», прославляемая в праздничных песнопениях, продолжаться в наших сердцах во все дни нашей жизни!

Библиотека Русской веры

Поучение св. Иоанна Златоустаго на святую Пасху →

Читать онлайн

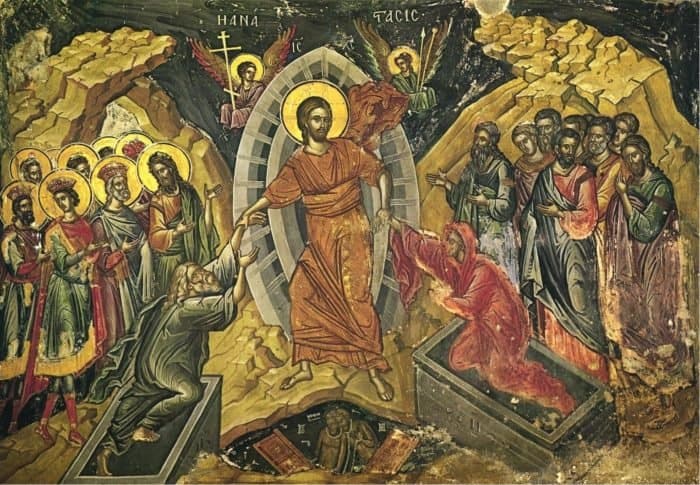

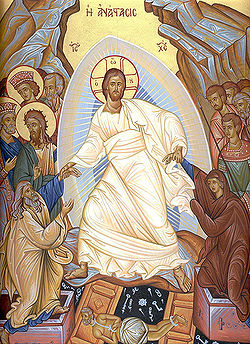

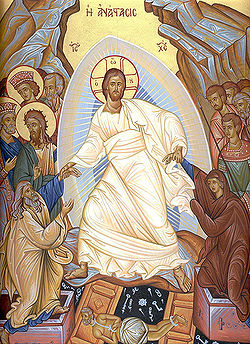

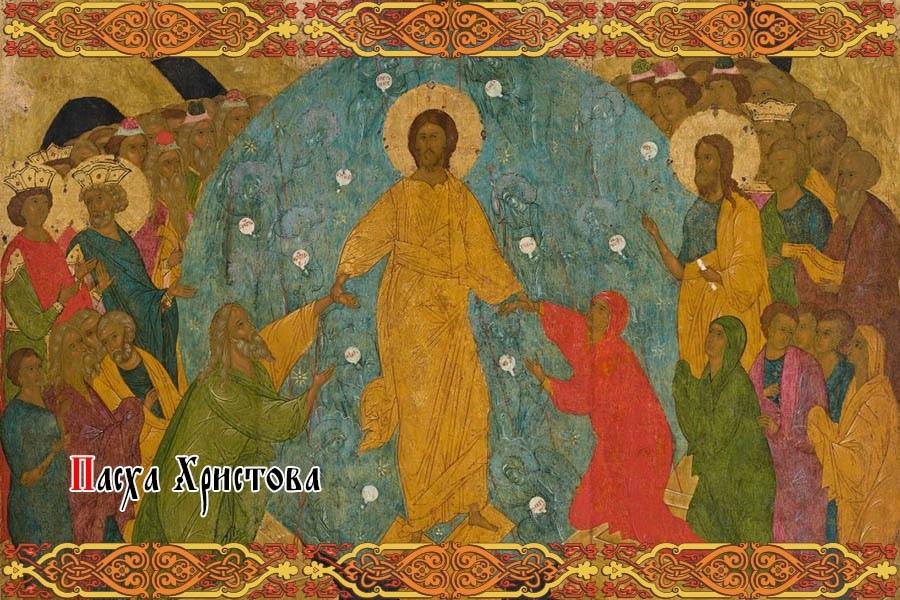

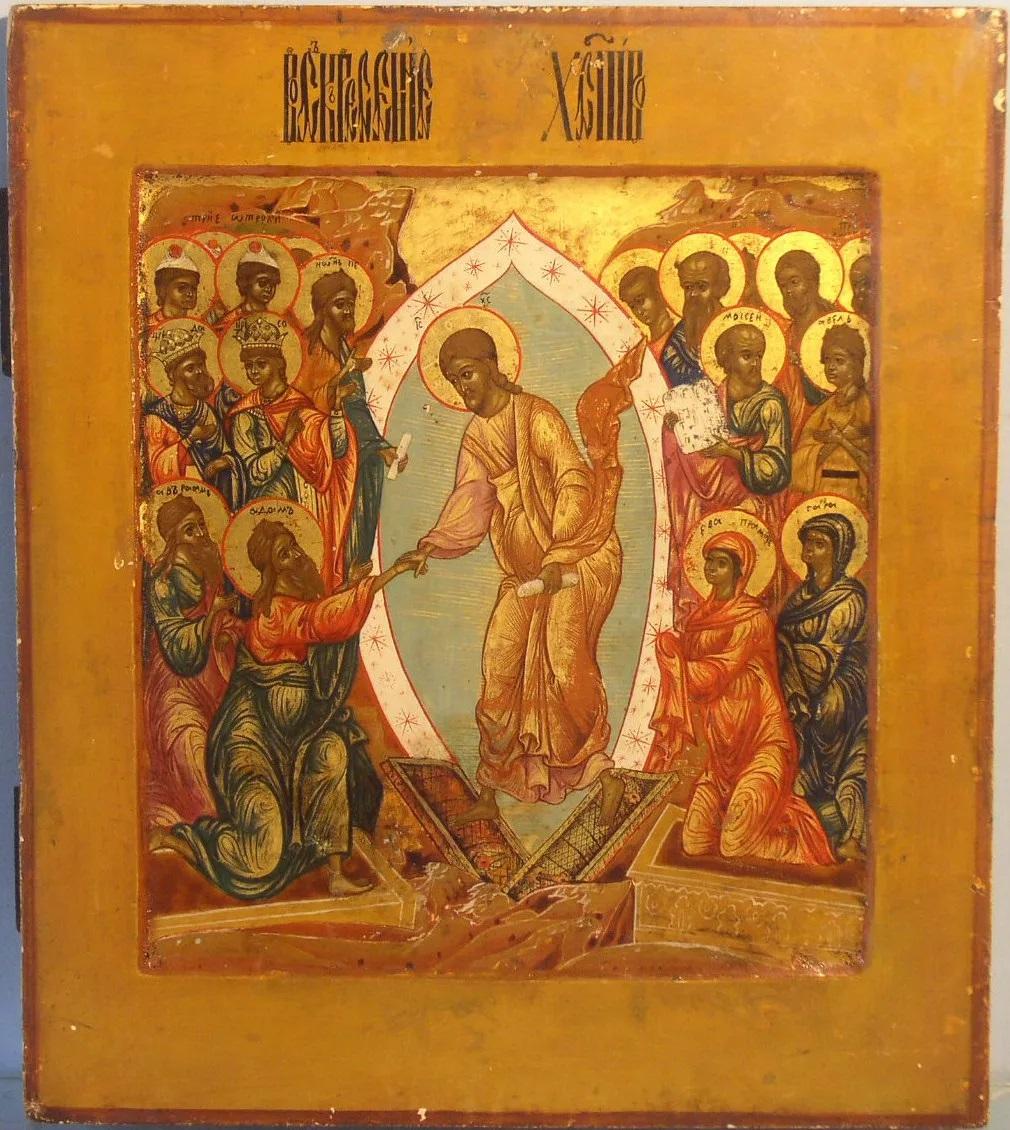

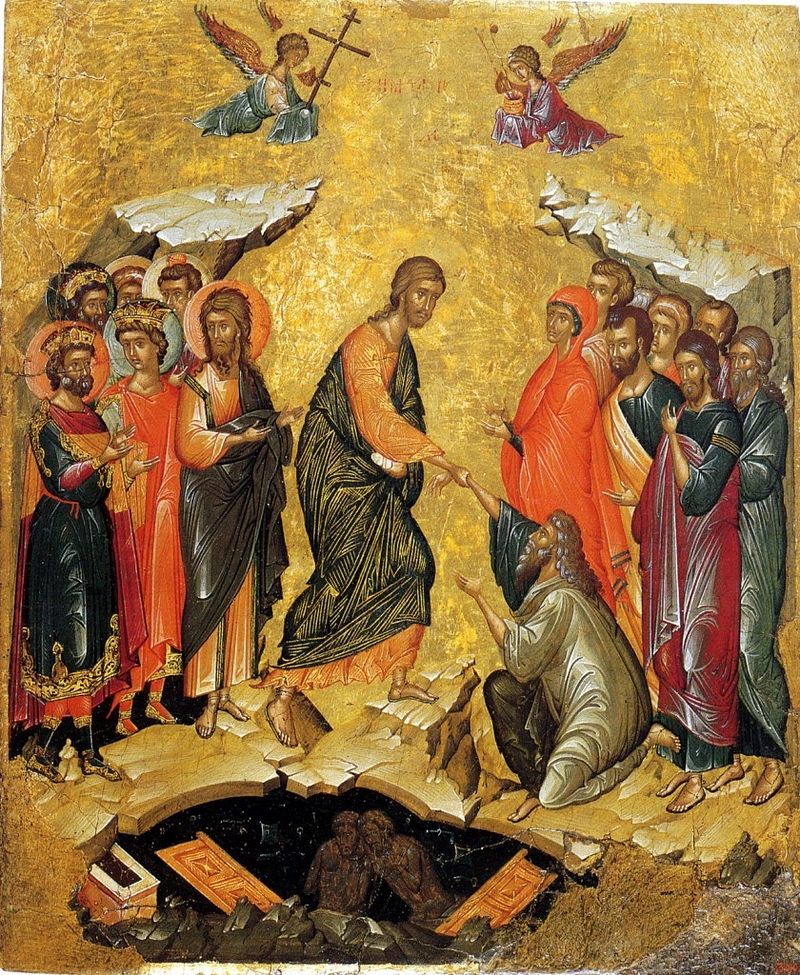

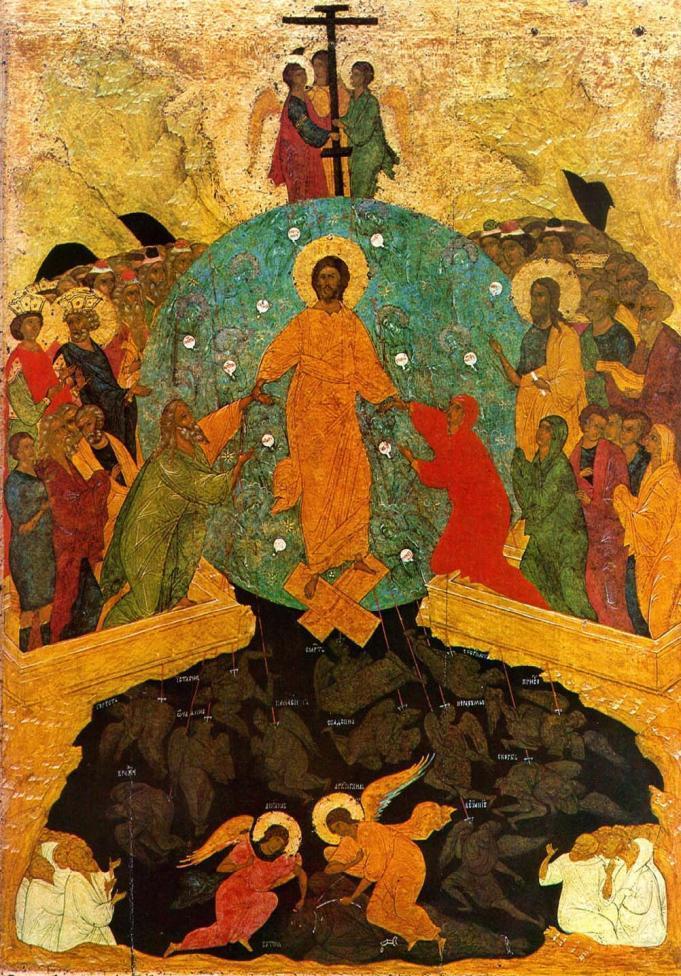

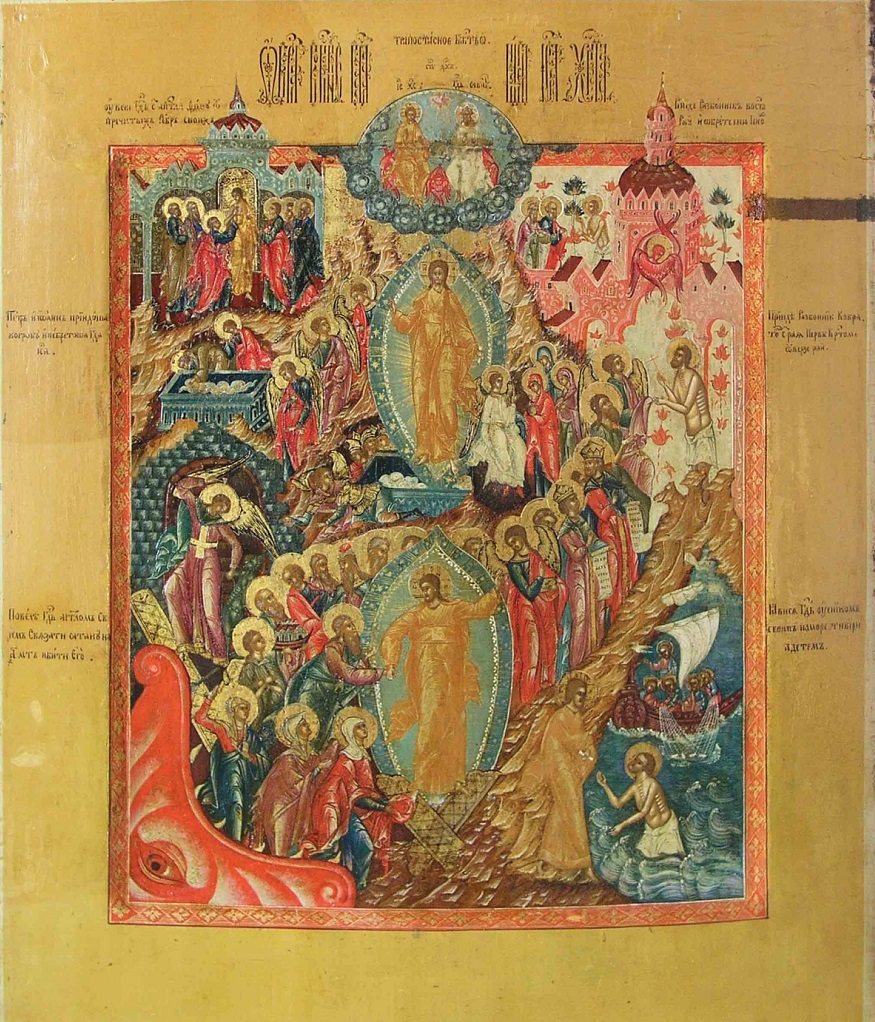

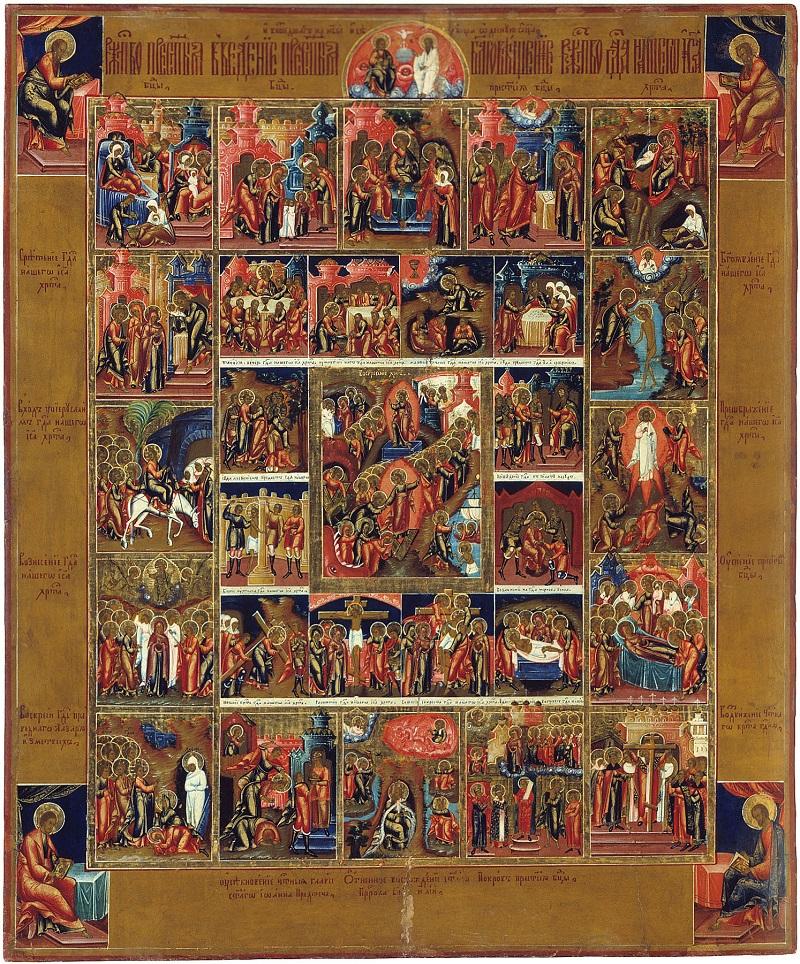

Воскресение Христово. Иконы

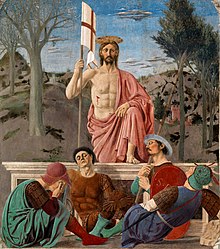

В старообрядческой иконографии нет отдельной иконы Воскресения Христова, потому что момент воскресения Исуса не видели не только люди, но даже ангелы. Этим подчёркивается непостижимость тайны Христа. Знакомое нам изображение Христа, в белоснежных ризах исходящего из гроба со знаменем в руке, — это позднейшая католическая версия, лишь в послепетровское время появившаяся в храмах РПЦ.

В православной иконографии на иконе Воскресения Христова, как правило, изображается момент схождения Спасителя в ад и изведения из ада душ ветхозаветных праведников. Также иногда изображается воскресший Христос в сиянии, ангел, благовествующий Женам-мироносицам, и другие сюжеты, связанные с Воскресением. Сюжет «Воскресение Христово — Сошествие во ад» является одним из наиболее распространенных иконографических сюжетов.

Общая идея пасхального изображения Христа в аду созвучна теме Исхода народа Израильского из Египта. Как некогда Моисей освободил евреев от рабства, так и Христос исходит в преисподнюю и освобождает томящиеся там души. И не просто освобождает, а переводит их в царство Правды и Света.

Храмы Воскресения Христова

Самым известным храмом Воскресения Христова является Храм Гроба Господня (Иерусалимский храм Воскресения Христова).

Храмы Воскресения Христова на Руси строились во имя Воскресения Словущего, или Обновления, то есть освящения после восстановления Храма Гроба Господня, совершенного в 355 году при святом равноапостольном Константине Великом.

В Москве сохранились несколько храмов в честь этого праздника, один из них — храм Воскресения Словущего на Успенском Вражке. Первое упоминание о храме датируется 1548 годом. Это была деревянная церковь, которая сгорела в большой московский пожар 10 апреля 1629 года. На её месте к 1634 году был построен существующий каменный храм. Почти два века храм простоял без изменений, в 1816—1820 годах были перестроены трапезная и колокольня.

Один из древнейших храмов в г. Коломне освящен в честь Воскресения Словущего. 18 января 1366 года в этом храме венчались святой благоверный князь Дмитрий Донской и святая княгиня Евдокия (в иночестве Евфросиния) Московская. Храм неоднократно перестраивался. В 1990-х гг. он возвращен приходу Успенского собора РПЦ.

Во времена Золотой Орды в Коломенском посаде был воздвигнут храм во имя Николы «Мокрого», упомянутый в писцовых книгах 1577—1578 годах. В начале ХVIII века на его месте построен храм с главным престолом в честь Воскресения Словущего и придельным храмом во имя святителя Николы. В начале 1990-х годов этот один из старейших и красивейших храмов города Коломны администрация передала общине Русской Православной старообрядческой Церкви. Главный храмовой праздник теперь отмечается 19 декабря, в честь св. Николы «зимнего», а в народе этот храм до сих пор многие знают как храм Воскресения Христова.

Старообрядческие храмы Воскресения Христова

Знаменитая рогожская колокольня была освящена 18 августа 1913 года во имя Воскресения Христова, после того как на средства благотворителей этот храм был возведен в честь дарования старообрядцам свободы вероисповедания. После того, как во время гонений безбожников храм был осквернен, его нужно было переосвятить. В 1949 году он был освящен во имя Успения Пресвятой Богородицы, поскольку старый антимис во имя Воскресения Христова исчез, однако на Рогожском хранился антимис, освященный во имя Успения Божией Матери. В таком положении храм пребывал до 31 января 2014 года. В конце 1990-х годов стали изучать предложения вернуть храму его историческое имя. После реконструкции и капитального ремонта храма в 2012 году его необходимо было переосвятить. Инициатива переосвятить храм с его историческим наименованием была поддержана предстоятелем Русской Православной старообрядческой Церкви митрополитом Корнилием (Титовым) на Освященном соборе 2014 года. 1 февраля 2015 года в Рогожской слободе состоялось освящение храма-колокольни Рогожского кладбища во имя Воскресения Христова. Таким образом ему было возвращено историческое имя.

Древлеправославной Поморской Церкви принадлежит действующий храм Воскресения Христова и Покрова Богородицы в Токмаковом переулке (г. Москва). Это первая старообрядческая церковь поморской общины (2-й Московской общины поморского брачного согласия), возведённая после манифеста о веротерпимости 1905 года в Москве. История у этого храма очень многострадальная. Сейчас продолжается реставрация храма на средства членов общины, при этом проходят службы.

Также в Литве в г. Висагинасе действует храм Воскресения Христова Древлеправославной Поморской Церкви.

Христианская Пасха и Песах у иудеев (Еврейская Пасха)

В 2021 году православные празднуют Пасху 2 мая, а иудейский праздник Песах (Еврейская Пасха) в этом году прилучается на 27 марта–4 апреля. Таким образом, многие внимательные христиане задаются вопросом: «Почему в 2017 году православные празднут Пасху вместе с иудеями?». Такой вопрос исходит из 7-го правила святых апостол, которое дословно звучит так:

Если кто, епископ, или пресвитер, или диакон святой день Пасхи прежде весеннего равноденствия с иудеями праздновать будет: да будет извержен от священного чина.

Получается, что якобы в этом году все православные будут нарушать 7-е апостольское правило? В сознании некоторых христиан получается целый «экуменический клубок», когда в 2017 году православные, католики и иудеи празднуют Пасху в один день. Как же быть?

Для разрешения этого вопроса следует знать, что споры о вычислении дня Пасхи в Православной церкви, по сути, закончились с утверждением православной Пасхалии на Первом Вселенском соборе. Таблицы Пасхалии позволяют вычислять день Пасхи календарно, то есть не глядя на небо, а с помощью календарных таблиц, циклически повторяющихся каждые 532 года. Эти таблицы были составлены так, чтобы Пасха удовлетворяла двум апостольским правилам о Пасхе:

- Праздновать Пасху после первого весеннего полнолуния (то есть после первого полнолуния, наступившего после дня весеннего равноденствия);

- не сопраздновать Пасху с иудеями.

Поскольку эти два правила не определяют день Пасхи однозначно, к ним были добавлены еще два вспомогательных правила, которые совместно с апостольскими (главными) правилами позволили определить Пасху однозначно и составить календарные таблицы православной Пасхалии. Вспомогательные правила не так важны, как апостольские, и к тому же одно из них со временем начало нарушаться, поскольку календарный способ вычисления первого весеннего полнолуния, заложенный в Пасхалию, давал небольшую ошибку — 1 сутки за 300 лет. Это было замечено и подробно обсуждалось, например, в Собрании святоотеческих правил Матфея Властаря. Однако поскольку данная ошибка не затрагивала соблюдения апостольских правил, а лишь усиливала их, сдвигая день празднования Пасхи немного вперед по датам календаря, в Православной церкви было принято решение не менять Пасхалию, утвержденную отцами Вселенского собора. В Католической же церкви Пасхалия была изменена в 1582 году таким образом, что потерявшее силу вспомогательное правило стало вновь выполняться, зато апостольское правило о несопраздновании с иудеями начало нарушаться. В итоге Православная и Католическая Пасхи разошлись во времени, хотя иногда они могут совпадать.

Если посмотреть на два апостольских правила, приведенных выше, бросается в глаза, что одно из них — о несопраздновании с иудеями — изложено не совсем строго и требует толкования. Дело в том, что празднование иудейской Пасхи продолжается 7 дней. Православная Пасха, по сути, тоже празднуется 7 дней, в течение всей Светлой седмицы. Возникает вопрос: что значит «не сопраздновать с иудеями»? Не допускать совпадения Светлого воскресения с первым днем иудейской Пасхи? Или же подойти более строго и не допускать наложения Светлого воскресения ни на один из 7 дней иудейского праздника?

На самом деле, внимательно изучая Пасхалию, можно заподозрить, что ранее Первого Вселенского собора христиане пользовались как первым (слабым), так и вторым (сильным) толкованием апостольского правила. Однако отцы Первого Вселенского собора при составлении Пасхалии совершенно определенно остановились именно на первом толковании: Светлое воскресение не должно совпадать лишь с первым, основным днем иудейской Пасхи, а с последующими 6-ю днями иудейского праздника оно совпадать может. Таково было ясно выраженное в Пасхалии мнение Первого Вселенского собора, которому до сих пор следует Православная Церковь. Таким образом, в 2017 году православные не нарушают 7-е правило святых апостол о праздновании Пасхи с иудеями, потому как христианская Пасха не совпадает с первым днем еврейской Пасхи, а в остальные дни такие «наложения» не возбраняются, тем более, что подобные случаи были и ранее.

Новопасхалисты и их учение

В наше время, в 2010 году, несколько членов Русской Православной старообрядческой Церкви усомнились в святоотеческом толковании апостольского правила о Пасхе и решили пересмотреть этот вопрос. Собственно, пересмотром занимался один только А. Ю. Рябцев, а остальные ему просто поверили на слово. А.Ю. Рябцев, в частности, писал (мы цитируем его слова частично, опуская явные домыслы):

… Нередко наша Пасха совпадает с последними днями еврейской пасхи, которая празднуется семь дней, и первое главное правило вычисления Пасхи нарушается… В современной практике мы иногда попадаем на последние дни еврейской пасхи.

А. Ю. Рябцев предложил запретить совпадение Светлого воскресения со всеми 7-ю днями иудейского праздника Пасхи и праздновать Православную Пасху по новым, им самим предложенным правилам. Сторонников этого учения стали называть «новопасхалисты» или «новопасхальники». 1 мая 2011 года они впервые отметили Пасху по новым правилам в древнем пещерном храме на горе Тепе-Кермен в Крыму. После собора РПсЦ 2011 года, осудившего празднование Пасхи по новым вычислениям, новопасхалисты выделились в отдельную религиозную группу, существующую и поныне. В нее входит всего несколько человек. По-видимому, существует некая связь между этой группой и Г. Стерлиговым, также высказывавшим мысль об изменении дня празднования Православной Пасхи.

В нашей стране примерно 90% православных христиан никогда не читали Новый Завет (не говоря уже о других Священных книгах), но многие из них свято чтят все религиозные традиции, соблюдают посты. А такие праздники как Пасха или Рождество отмечают абсолютно все, не имея при этом ни малейшего представления об их значении и истории возникновения. Поэтому, когда почти любому из них задаёшь, казалось бы, элементарный вопрос: «А зачем ты каждый год на Пасху красишь яйца и покупаешь куличи? Что всё это означает?» — в 99% случаях получаешь примерно вот такой вот ответ:

— Ты чо, дурачёк что ли? Так ВСЕ делают. Это же праздник!

— Чей праздник? Зачем всё это?

После чего твой православный собеседник начинает что-то невразумительно мычать, злиться и отмахиваться от тебя. А дальнейшие расспросы и уточнения вводят его в состояние дичайшего батхёрта и попоболи.

Но наших бабушек ещё можно понять и простить — они не пользуются этими вашими интернетами, да и вообще выросли в другом государстве, где главенствовал атеизм. Мракобесие более молодых поколений оправдать сложнее. К тому же мало кто из них знает, что ещё относительно недавно сама церковь запрещала все эти яйца, куличи и прочие сегодняшние пасхальные атрибуты, считая их богомерзким язычеством.

В общем для всех интересующихся данными вопросами я и написал этот небольшой обзорный пост.

Ветхий Завет.

Пасха, или по-еврейски Песах, берёт своё начало с тех далёких ветхозаветных времён, когда евреи находились в рабстве у египтян.

Однажды пастуху Моисею явился Б-г в образе несгораемого кустарника (Исх.3:2) и повелел ему идти в Египет, чтобы вывести оттуда израильтян и переселить их в Ханаан. Это необходимо было сделать для того, чтобы спасти евреев от голода, т.к. за 400 лет пребывания в египетском рабстве их численность возросла в семь раз. И фараону, чтобы справиться с демографическим взрывом, даже пришлось устроить им настоящий геноцид: сначала он изнурял евреев тяжёлыми работами, а потом и вовсе приказал «повивальным бабкам», принимающим роды, умерщвлять еврейских младенцев мужского пола. (Исх.1:15-22).

Но на просьбы Моисея отпустить евреев фараон не соглашался. И тогда Бог-Яхве, выражаясь современным языком, — устроил массовый террор коренного египетского населения, в виде погромов, поджогов, убийств и светопреставлений. Все эти бедствия получили в Пятикнижии название «Десять казней египетских»:

Казнь №10: умерщвление первенца фараона.

Сначала Аарон — старший брат и подельник Моисея — отравил пресную воду в местных водоёмах (Исх.7:20-21)

Затем Г-сподь устроил им дичайшие нашествия насекомых и земноводных (казнь жабами, наказание мошками, пёсьими мухами и саранчой (Исх.8:8-25).

Далее Он устраивал египтянам мор скота, вызывал дерматологические эпидемии, обрушивал огненный град, на трое суток погружал население во тьму. А когда и всё это не помогло — прибегнул к крайним мерам — массовым убийствам: умертвив всех первенцев (за исключением еврейских). (Исх.12:29).

В общем, На следующий день напуганный фараон, чей первенец тоже погиб, — отпустил всех евреев с их скотом и пожитками.

А Моисей повелел каждый год отмечать Пасху в память о дне освобождения от рабства.

Исход евреев из разоренных египетских земель.

Но причём здесь крашеные яйца и праздничные куличи?

Новый Завет.

Именно в память о тех событиях Иисус Христос отпраздновал в последний раз Пасху в 33 году нашей эры. Стол был скромным: вино — как символ крови жертвенного ягнёнка, пресный хлеб и горькие травы в знак памяти о горечи бывшего рабства. Это и был последний ужин Иисуса и апостолов.

(Кстати, ещё об одном ритуале, связанным с массовыми убийствами парнокопытных млекопитающих, я расскажу перед Курбан-Байрамом).

Тайная вечеря: последняя трапеза Иисуса Христа со Своими двенадцатью ближайшими учениками, во время которой Он установил таинство Евхаристии и предсказал предательство одного из учеников.

Однако, в Библии говорится, что накануне ареста Иисус изменил значение праздничных блюд. В Евангелие от Луки сказано следующее: «Затем он взял хлеб, воздал благодарность Богу, разломил его и дал им, сказав: «Это означает моё тело, которое будет отдано за вас. Делайте это в воспоминание обо мне». Точно так же он взял и чашу после ужина, сказав: «Эта чаша означает новое соглашение на основании моей крови, которая прольётся за вас.» (Луки 22:19,20).

Таким образом, Иисус предрёк свою смерть, но так или иначе Он не велел Своим ученикам отмечать Пасху в честь Его воскресения. В Библии нет ни единого упоминания об этом.

Апостолы и первые христиане отмечали годовщину воспоминания о смерти Иисуса, каждый год 14 нисана по еврейскому календарю (конец марта / начало апреля по-нашему). Это была памятная вечеря, на которой

ели пресный хлеб и пили вино

.

Таким образом, пока иудеи праздновали свой Песах как освобождение от египетского рабства — у первых христиан Паска являлась днём скорби. Т.к.за следующие два века христианство успешно набрало популярность, стремительно нарастив «свой электорат» — стали появляться первые противоречия как в праздновании Пасхи, так и в самой дате её проведения. Но об этом немного позже.

Первый Никейский (Вселенский) собор.

Задолго до прихода христианства римляне поклонялись собственному Богу Аттису, покровителю растений. Здесь можно проследить интересное совпадение: римляне верили, что Аттис родился в результате непорочного зачатия, погиб молодым из-за гнева Юпитера, но воскрес через несколько дней после смерти. И в честь его воскрешения люди стали устраивать каждую весну ритуал: рубили дерево, к нему привязывали статую юноши и несли его на площадь города с плачем. Затем начинали танцевать под музыку, и вскоре впадали в транс: доставали ножи, наносили себе небольшие увечья в виде колото-резаных ран, а своей кровью кропили дерево со статуей. Таким образом римляне прощались с Аттисом. Кстати, они соблюдали пост и постились вплоть до праздника воскрешения.

В романе Дена Брауна «Код да Винчи» есть один интересный момент, где один из героев подробно рассказывает о том, как кандидатуру Христа утверждали «на должность Бога» на Первом Никейском (Вселенском) Соборе, состоявшемся в 325 году. Данное событие имело место быть в истории.

Первый Никейский (Вселенский) собор. 325 г. На нём был утверждён Иисус и была произведена реформация празднования Пасхи.

Именно тогда римский император Константин I, опасаясь раскола общества по религиозному признаку, сумел соединить воедино две религии, сделав основной государственной религией — Христианство. Поэтому многие христианские обряды и таинства так похожи на языческие и имеют столь диаметрально противоположные «с первоисточником» значения. Это коснулось и празднования Пасхи. И в том же 325 году христианская Пасха была отделена от иудейской.

Но где же яйца — спросите вы? Скоро и до них дойдём. а пока ещё одно необходимое уточнение:

Расчёт даты Пасхи.

Споры о правильном определении даты празднования Пасхи не утихают до сих пор.

Общее правило для расчёта даты Пасхи: «Пасха празднуется в первое воскресенье после весеннего полнолуния».

Т.е. это должно быть: а) весной, б) первое воскресенье, в) после полнолуния.

Сложность вычисления также обусловлена смешением независимых астрономических циклов:

— обращение Земли вокруг Солнца (дата весеннего равноденствия);

— обращение Луны вокруг Земли (полнолуние);

— установленный день празднования — воскресенье.

Но не будем лезть в дебри этих расчётов и сразу перейдём к главному:

Вытеснение язычества на Руси христианством.

Не будем также углубляться в основные исторические печальные факты тех далёких лет, чтобы не превращать пост в километровый трактат по истории Древней Руси — а лишь слегка и только с одной стороны коснёмся её, назвав основные события, предопределившие насаждение христианства на территории нашего государства.

В христианизации Руси была заинтересована Византия. Считалось, что любой народ, принявший христианскую веру из рук императора и константинопольского патриарха, автоматически становится вассалом империи. Контакты Руси с Византией способствовали проникновению христианства в русскую среду. На Русь был послан митрополит Михаил, крестивший, по преданию, киевского князя Аскольда. Христианство было популярно среди дружинников и купеческой прослойки при Игоре и Олеге, а княгиня Ольга и вовсе сама стала христианкой во время визита в Константинополь в 950-х годах.

В 988 году Владимир Великий крестит Русь, и начинает бороться с языческими праздниками по совету византийских монахов. Но тогда для русичей христианство было чужой и непонятной религией, и если бы власть начала открыто бороться с язычеством – народ бы взбунтовался. Кроме того, огромный авторитет и влияние на умы имели волхвы. Поэтому была выбрана тактика несколько другая: не силой, а хитростью.

Каждому языческому празднику постепенно давалось новое, христианское значение. Также христианским святым были приписаны привычные для русичей признаки языческих богов. Таким образом, «Коляда» — древний праздник зимнего солнцестояния — постепенно трансформировался в рождество Христово. «Купайло» — летнее солнцестояние — переименовали в праздник Иоанна Крестителя, которого в народе до сих пор называют Иваном Купалой. А что касается христианской Пасхи, то она совпала с очень особенным русским праздником, который назывался «Великдень». Этот праздник был языческим Новым Годом, и его праздновали в день весеннего равноденствия, когда оживала вся природа.

Праздник Великодня: самого важного праздника в календаре восточных и западных славян.

Наши предки, готовясь к Великодню, разрисовывали яйца и пекли куличи. Но вот только значения этих символов совсем не были похожи на христианские. Когда впервые византийские монахи увидели, как люди отмечают этот праздник — они объявили его страшным грехом, и стали всячески с этим бороться.

Пасхальные яйца и куличи.

Была раньше такая игра, которая называлась «красное яичко». Мужчины брали раскрашенные яйца и бились ними друг с другом. Выигрывал тот, кто разобьёт больше всего чужих яиц при этом не разбив своего. Это делалось для того, чтобы привлечь женщин, так как считалось, что победивший мужчина будет самым крепким и лучшим. У женщин был такой же ритуал – но их битва крашеными яйцами кагбэ символизировала оплодотворение, так как яйцо у многих народов мира считалось издавна символом весеннего возрождения и новой жизни.

Битьё яиц проводилось не только в развлекательно-игровых целях, но и для того, чтобы задобрить богиню плодородия Макошь. Задабривая её таким образом, они надеялись на будущий богатый урожай, размножение скота и рождение детей.

По одной из вариаций Макошь — Мокошь. Оно возникло от слова «мокнуть». Символом Макоши считалась вода, дающая жизнь земле и всем живым существам.

Некоторые считают, что обычай печь куличи на Пасху пошёл от евреев, которые пекли свой пасхальный хлеб, который называется маца. Это не так. Сам Иисус разламывал хлеб и угощал им апостолов на тайной вечере, но этот хлеб был плоским и пресным. А кулич делают рыхлым, с изюмом, и посыпают сверху глазурью, а потом меряются – чей типа выше вырос.

Эта традиция возникла задолго до того, как христианство пришло на Русь. Наши предки поклонялись солнцу и верили, что Даждьбог каждую зиму умирает, и рождается заново весной. И в честь нового солнечного рождения в те времена каждая женщина должна была выпечь свой кулич в печи (символе женского лона) и исполнить над ней родильный ритуал. Выпекая кулич, женщины поднимали подол, имитируя беременность. Это считалась символом новой жизни.

Как можно догадаться, выпекаемый кулич, имеющий цилиндрическую форму, покрытый белой глазурью и посыпанная семенами является ни чем иным, как эрегированным мужским половым х.. членом. Предки относились к таким ассоциациям спокойно, потому что для них было главным, чтобы земля давала урожай, а женщины рожали. Поэтому после того, как пасху доставали из печи, на ней рисовали крест, который был символом бога солнца. Даждьбог отвечал за плодовитость женщин и за плодородие земли.

Эти сходства Даждьбога с Иисусом Христом: воскрешение и главный символ – крест, по мнению историков и явились главными признаками, по которым византийской церкви удалось успешно слить воедино язычество и христианство.

Чистый четверг и зомбоапокалипсис.

В отличие от Пасхи первых христиан, употреблявших исключительно пресный хлеб с вином, наши предки праздновали Великдень по полной программе: с мясом, колбасами и прочими вкусностями. С установлением христианства церковь запретила употреблять мясное на праздник. Однако раз в году мясными блюдами угощали не простых гостей, а покойников. Назывался этот ритуал — «Радуницы»:

Люди собирались на кладбищах в четверг, перед Великоднем. Они приносили в корзинах еду, раскладывали её на могилах, и потом начинали громко и протяжно звать своих умерших, просить, чтобы те вернулись в мир живых, и попробовали вкусную еду. Считалось, что именно в четверг перед Великоднем предки выходили из земли и оставались рядом с живыми людьми до следующего воскресенья после праздника. В это время их нельзя было называть покойниками, потому, что они слышат всё, о чём говорят, и могут обидеться. Люди тщательно готовились к «встрече» с родственниками: задабривали домовых небольшими жертвами, вешали обереги и убирались в домах.

На сегодняшний день этот совсем недобрый праздник поделился на два радостных: в чистый четверг — когда хозяйки устраивают генеральную уборку в доме, и в проводное воскресенье — когда все наши бапки дружною гурьбой устремляются на кладбища и выкладывают там на могилах своих родственников крашеные яйца и куличи.

Но такая перемена произошла не сразу. С языческими ритуалами довольно долго и жёстко боролись, а в XVI веке к этой борьбе подключился даже Иван Грозный, который пытался избавиться от двоеверия. Во исполнение указов Ивана Грозного, священники начали присматривать за религиозным порядком и даже шпионить. Но это не помогло, народ по-прежнему чтил свои традиции, и как и прежде в домах люди продолжали исполнять языческие ритуалы, а на глазах ходили в церковь. И церковь сдалась. В XVIII веке языческие символы были объявлены христианскими, им было даже придумано божественное происхождение. Так символом Христового воскресения стали яйца плодородия, а хлеб Даждьбога превратился в символ Иисуса Христа.

Эпилог.

Теперь, бразы и систы, вы знаете о Пасхе практически всё. Осталось только провести небольшую параллель.

За многие века Пасха, как и наш День победы, превратилась из Дня скорби по погибшим — в праздничную вакханалию. Почти никто уже не знает и не помнит, с чего всё началось и зачем всё это нужно. Просто ещё один праздничный день, с которого можно православно набухаться и безнаказанно уйти в аццкий христианский запойно-угарный отрыв.

Теперь же вы будете ЗНАТЬ — за что пить. И пить ли вообще. Ведь, возможно, для кого-то этот день окажется днём скорби. Или днём больших невесёлых раздумий…

К О Н Е Ц

Подписывайтесь на мой телеграмм-канал: https://t.me/uvova1

#пасха, #песах, #Моисей, #великдень

Церковное пасхальное богослужение ведет свое начало из глубокой христианской древности. В течение столетий оно дополнялось новыми обрядами и песнопениями, пока, наконец, приняло современный вид.

Основание церковному богослужебному году было положено в век апостольский празднованием воскресного дня. Первое определенное указание на празднование воскресного дня находится в 1‑м Послании ап. Павла к коринфянам (1Кор.16:1-2). В Книге Деяний (Деян.20:7-8, 11) имеется указание на освящение воскресного дня богослужебным собранием. В Троаде «в первый день недели, когда ученики собрались для преломления хлеба, Павел… беседовал с ними и продолжил слово до полуночи… преломив хлеб и вкусив, беседовал довольно, даже до рассвета». Как видим, воскресный день («первый день недели») освящался совершением Евхаристии. Дееписатель отмечает также, что в горнице, где происходило преломление хлеба, было «довольно светильников».

О праздновании еженедельного воскресного дня всей Церковью после апостольских времен упоминают многие церковные писатели. Так, св. Игнатий Богоносец, ученик ап. Павла, в Послании к магнезийцам советует оставить хранение субботы и жить «жизнью Воскресения, в котором и наша жизнь воссияла чрез Него и чрез смерть Его» («Писания мужей апостольских», в перев. прот. П. Преображенского. СПб., 1895, с. 282).

О еженедельном праздновании христианами воскресного дня упоминает в начале II века и Плиний Младший. «Они, — пишет Плиний, — …имеют обыкновение собираться в определенный день перед рассветом и петь гимны Христу, как Богу…».

В обращении к язычникам древние церковные писатели (св. Иустин Философ, Тертуллиан и др.) часто называли воскресный день днем солнца, потому что так назывался у язычников этот день недели. В обращении же к иудейской среде они, когда нужно было отличить воскресный день от субботы, называли его днем воскресения Господня и просто днем Господним.

Если первые христиане сохраняли иудейские обычаи, в том числе празднование субботы, то во II веке воскресный день вытесняет субботу, а Лаодикийский Собор 29‑м правилом прямо запрещает христианам «иудействовать», то есть праздновать субботу, и повелевает всем «день воскресный преимущественно праздновать».

День воскресный освящается и празднуется и доныне в каждом обществе христиан. Прославляя Господа, воскресшего из мертвых, и торжествуя Его победу над смертью. Святая Церковь установила еженедельно совершать богослужение в радостный день Воскресения Христова без обязательных коленопреклонении в молитве.

У писателей раннего христианства имеются сведения и о праздновании ежегодного дня смерти и Воскресения Христова, то есть Пасхи (Послание св. Иринея, епископа Лионского, к епископу Римскому Виктору; две книги о Пасхе Мелитона, епископа Сардийского; писания Аполлинария, епископа Иерапольского, Климента Александрийского, св. Ипполита, папы Римского, и др.).

Исследуя сочинения этих церковных писателей, можно прийти к выводу, что первоначальное празднование Пасхи было празднованием страданий и смерти Христовых — «Пасха крестная», так сказать, «догматическая Пасха» — 14 нисана, в день еврейской Пасхи,— при этом празднование сопровождалось постом, — и затем празднованием собственно Воскресения Христова — «Пасха воскресная», или «историческая Пасха», то есть соответствующая последовательности евангельских событий, в виде торжественного прекращения поста в вечер того же дня 14 нисана или в следовавшее за ним воскресенье. (Практика разных Церквей Востока и Запада была в последнем отношении различной. Пасха Воскресения не везде могла праздноваться с самого начала.) «Возможно, что слова Спасителя, — говорит, основываясь на многих древних свидетельствах, проф. М. Скабалланович, — «егда же отнимется от них жених, тогда постятся», выставленные таким древним писателем, как Тертуллиан, в качестве основания для пасхального поста, были поняты в этом смысле и самими апостолами и побуждали их освящать постом, который они вообще любили (Деян. 13:2), годовой день смерти Господней… В виде такого поста и существовала “первоначально Пасха, как убедимся из первоначального свидетельства о ней во II в. у св. Иринея. Даже в III в. Пасха сводилась к посту, была крестной Пасхой, подле которой еще и тогда едва лишь начала выступать в качестве самостоятельного праздника Пасха Воскресения — под видом торжественного оставления пасхального поста» (Толковый Типикон, вып. 1‑й, Киев, 1910, с. 45). Во всяком случае, канонические памятники III в. — Каноны Ипполита, Египетские постановления, Сирская Дидаскалия и «Завещание Господа» (в основе своей памятник II в.) — еще сохраняют взгляд на Пасху как на пост.

Если на Пасху вначале могли смотреть как на пост в память смерти Спасителя, умершего в день еврейской Пасхи, то вскоре начинают соединять с ней и радостное воспоминание о Воскресении Христовом и приурочивать это событие к воскресному дню, а не к любому дню недели, на который приходилась бы еврейская Пасха, и особенно это было заметно в Западной Церкви.

С течением времени из празднования Пасхи крестной образовалась Страстная седмица (в древности она называлась «великой седмицей»), с ее торжественно-скорбными богослужениями, из Пасхи же воcкресной — собственно Пасха с Светлой седмицей, а древняя практика крещения оглашенных на Пасху с предшествовавшим этому их оглашением (наставлением в истинах веры) за богослужениями, во время которого они, проводя время в посте и молитвах, знакомились с содержанием Священного Писания, начиная с книги Бытия, дала начало посту Св. Четыредесятницы. Сорокадневная продолжительность этого поста установлена в память и подражание сорокадневному посту Иисуса Христа пред началом Его служения делу нашего спасения. В современном Уставе сохранились следы древнего празднования Пасхи крестной и Пасхи воскресной. Это заметно в праздничном характере служб Великих четвертка, пятка и субботы и в структуре бдения на Пасху, состоящего из торжественно-скорбной пасхальной полунощницы, с каноном Великой субботы, и из торжественно-радостной пасхальной утрени. (Что службы пасхальных полунощницы и утрени составляют одно целое, видно из того, что при совпадении Благовещения с Пасхой Устав назначает петь канон Благовещению на полунощнице и на утрене.)

IV век ознаменовался прекращением гонений, и это, конечно, оказало благотворное воздействие на создание торжественности всех церковных служб, и тем более пасхальной. Этому способствовали также меры по усугублению торжественности православных богослужений, проводившиеся великими иерархами Церкви в борьбе с арианством, которое привлекало последователей внешней пышностью своих религиозных процессий. О величии и торжественности совершения пасхального богослужения в этот период можно судить по Пасхальным Словам таких отцов, как свв. Иоанн Златоуст, Василий Великий, Григорий Богослов, Григорий Нисский и другие. Св. Григорий Нисский в своем Слове на Пасху говорит: «Слух наш оглашается во всю светлую ночь словом Божиим, псалмами, пениями, песнями духовными, которые, втекая в душу радостным потоком, преисполняли нас благими надеждами, и сердце наше, приходя в восхищение от слышимого и видимого, возносилось чрез чувственное к духовному, предвкушало несказанное блаженство, так что блага сего покоя, удостоверяя собою в неизреченной надежде на получение уготованного, служат для нас образом тех благ, «ихже око не виде, и ухо не слыша, и на сердце человеку не взыдоша» (1Кор.2:9)».

Обстоятельные и интересные сведения о торжественности совершения служб Святых Страстей и Пасхи в Иерусалимской Церкви в IV веке дают записки паломницы IV века Этерии (Сильвии Аквитанки), — в частности сведения о схождении св. огня, крещении оглашенных в Великую субботу и т. д.

С IV в. утверждается семидневное празднование Св. Пасхи, что видно из писаний свв. Кирилла Иерусалимского, Иакова Низибийского и Иоанна Златоуста, который семидневное торжество Пасхи называет духовным браком (Слово против упивающихся и о Воскресении). Пасхальная служба начинается в ночное время и заканчивается с рассветом. Особенностью этого ночного пасхального богослужения является, по свидетельству историка Евсевия и других, возжжение множества светильников в храмах и в городах, благодаря чему «эта таинственная ночь становилась светлее самого светлого дня» (Евсевий. Жизнь Константина, IV, 22).

В дальнейшем пасхальное богослужение в основном не претерпевает особых изменений, а только пополняется новыми песнопениями. Те величественные песнопения, которые мы слышим в Светлый Праздник Пасхи, большею частью принадлежат св. Иоанну Дамаскину, который сложил их согласно с высокими выражениями о Пасхе священных писателей и древних отцов Церкви, преимущественно свв. Григория Богослова и Григория Нисского.

Нынешний порядок совершения пасхального богослужения сходен с уставами древнейших богослужебных памятников Православного Востока. Особенности утреннего “пасхального богослужения — отсутствие чтений (за исключением Слова св. Иоанна Златоуста), шестопсалмия, кафизм, литии, полиелея и великого славословия — весьма древнего происхождения. Они коренятся в особых торжественных богослужениях Древней Церкви, — так называемых песенных последованиях. совершавшихся в Великих (кафедральных церквах Константинополя, Антиохии, Солуни, о которых говорят Устав Великой Константинопольской церкви и блаж. Симеон Солунский и которые возникли первоначально в Великой церкви Иерусалимской,— о них еще в IV в. упоминает Сильвия Аквитанка (А. Дмитриевский, Богослужение Страстной и Пасхальной седмиц во св. Иерусалиме IX–Х в., Казань, 1894, с. 286–290). Указанные особенности имеются, например, в найденном и опубликованном А. Дмитриевским «Последовании Святых Страстей и Пасхальной недели в Иерусалиме IX–Х в.». Если же принять вместе с проф. А. Дмитриевским, что этот памятник сохраняет в своей основе практику богослужений V, VI и VII вв. (цит. соч., с. XV), то можно считать, что уже во времена Сильвии Аввитаяки и в ближайшие после ее времени столетия рассматриваемые особенности существовали в песненных последованиях Великой Иерусалимской церкви.

* * *

Божественной славе Воскресшего и величию светлого Праздника Пасхи, по современному Уставу, как и в древнее время, присуща высокая и особенная торжественность. Священнослужители перед началом утрени облачаются, по указанию Типикона, «в светлейшыя священныя одежды». С зажженными свечами, Евангелием и образом Воскресения, при пении стихиры «Воскресение Твое, Христе Спасе, ангели поют на небеси, и нас на земли сподоби чистым сердцем Тебе славити», которая сначала поется троекратно в алтаре, они выходят из храма с певцами и народом, совершая шествие вокруг храма, сопровождающееся торжественным звоном колоколов. Этим шествием, по изъяснению толкователей этого обряда; мы изображаем «мироносиц, шедших утру глубоку помазать Тело Христа Спасителя» (К. Никольский. Пособие к изучению Устава богослужения Православной Церкви. СПб., 1874, стр. 614).

В притворе храма начинается пасхальная утреня. Затем с радостной вестью «Христос Воскресе!» все входят в храм, как текли некогда жены-мироносицы в Иерусалим возвестить апостолам о Воскресении Господа.

Этой же песнью «Христос Воскресе», многократно повторяемой во время пения канона, Святая Церковь, «Царя Христа узрев из Гроба, яко Жениха происходяща», выражает неземной восторг праздничного торжества.

В конце пасхальной утрени при пении «Воскресения день, и просветимся торжеством, и друг друга обымем, рцем: «братие!», и ненавидящим нас простим вся Воскресением…» верующие приветствуют друг друга, произнося «Христос Воскресе!» и отвечая «Воистину Воскресе!», и запечатлевают это приветствие поцелуем и дарением пасхальных яиц.

С древнего времени на пасхальной заутрене читается «Слово огласительное св. Иоанна Златоуста на Пасху», сопровождаемое пением тропаря Свят. Иоанну.

Непосредственно после утрени, «безрасходно», по примеру храма Воскресения в Иерусалиме, начинается торжественное служение литургии.

Торжествуя и изображая во всех своих песнопениях, молитвословиях и священнодействиях победу Христа над смертью и начало вечной, блаженной жизни, Святая Церковь на пасхальной литургии антифонами из псалмов 65, 66 и 67 призывает всю вселенную воскликнуть Господу и воздать славу Ему.

В апостольском чтении (Деян.1:1-8) говорится о Воскресшем Иисусе Христе, Который пред Своими учениками «явил Себя живым в страдании Своем со многими верными доказательствами, в продолжении сорока дней являясь им и говоря о Царствии Божием» (Деян. 1), говорится и об обетовании апостолам Святого Духа.

Евангельское литургийное чтение (Ин.1:1-17) возвещает, что Воскресший есть Сын Божий, восприявший плоть человеческую, соделавший верующих чадами Божиими и явивший славу Свою, славу Единородного Сына Божия, полного благодати и истины, которыми Он наполняет верующих в Него и во всей полноте сообщает им то, что служит к богопознанию и богопочитанию, к просвещению и вечному блаженству. Это чтение Евангелия совершается на литургии первого дня Пасхи на многих языках во свидетельство того, что проповедь веры христианской, основанием которой является Воскресение Христово, огласила все народы, все концы земли. (В Греческой Церкви Евангелие на литургии читается обычным порядком, а на многих языках читается Евангелие на вечерне первого дня Пасхи).

Не менее торжественно совершается в первый день Пасхи и вечернее богослужение с чтением Евангелия, в котором повествуется о явлении Воскресшего Спасителя «дверем затворенным» в первый день воскресения ученикам в Иерусалиме (Ин.20:19-25).

В дни Святой Пасхи в православном народе с древних времен существует обычай вкушения освященных брашен. Христианская Пасха есть Сам Христос Своим Телом и Кровию: «Пасха—Христос Избавитель!» — поет Святая Церковь, повторяя слова ап. Павла (1Кор.5:7)

Поэтому в светлый день Пасхи особенно прилично причащаться Св. Тайн Тела и Крови Христовых, «но так как православные христиане имеют обычай принимать Св. Тайны в продолжение Великого поста и в Светлый день Воскресения Христова причащаются не многие, то по совершении литургии в этот день благословляются и освящаются в храме особенные приношения верующих, называемые пасхами, чтобы вкушение от них напоминало о причащении истинной Пасхи Христовой и соединяло всех верных во Иисусе Христе» (Прот. Г. Дебольский. Дни богослужения Правосл. Кафолич. Вост. Церкви, т. 2, СПб., 2, с. 14).

ЖМП. 1966. № 4. С. 52–56.

установленный в воспоминание Воскресения Иисуса Христа из мертвых. Он относится к подвижным праздникам, так как совершается каждый год в разное время. Пасху отмечают миллионы православных христиан во всем мире, в том числе и в России.

В нашей стране Пасху обычно празднуют позже, чем на Западе. Это происходит потому, что даты Пасхи определяются разными календарями. Русская православная церковь использует старый юлианский календарь, тогда как католическая и протестантская церкви перешли на григорианский календарь в 16 веке. Православный праздник Пасха в 2021 году отмечается 2 мая.

Существует несколько версий происхождения слова «Пасха». По одной из них, слово пришло из греческого языка и означает «прехождение», «избавление», то есть праздник Воскресения Христова, праздник Пасхи обозначает прохождение от смерти к жизни и от земли к небу

История праздника Пасхи

Суть христианского праздника Пасхи уходит корнями в Ветхий Завет, в книгу Исход, которая описывает первую Пасху и исход евреев из египетского рабства. Этот исход стал прообразом перехода человечества из рабства смерти и греха в Царство Божией свободы – свободы личности от вечной проблемы: угнетения и рабства, от факта конечности нашей жизни в перспективе вечности.

Традиция отмечать праздник Пасхи берет свое начало вовсе не с Воскресения Христа – она существовала и до этого. Еврейский праздник Пейсах отмечался и отмечается в ознаменование выхода израильского народа из египетского плена под предводительством Моше (Моисея).

История гласит, что когда-то евреи находились в рабстве у египтян и терпели всяческие лишения, однако, несмотря на это, они продолжали верить в Бога и ждать своего освобождения.

Бог направил к евреям их спасителей – человека по имени Моисей и его брата. Моисей обратился к египетскому фараону с просьбой освободить еврейский народ, но он отказался, так как не верил в Бога и поклонялся колдунам. Чтобы доказать существование и могущество Господне, на египетский народ было обрушено десять страшных казней. Правитель Египта был сильно напуган случившимся и отпустил евреев с их скотом, однако потом он передумал и отправился за ними в погоню. Когда евреи, возглавляемые Моисеем, дошли до моря, оно расступилось перед ними, и люди смогли перейти по его дну на другую сторону. Фараон бросился за ними, но вода поглотила его. От этих событий и ведется история праздника Пасхи, и с тех пор Пасха означает «прошедший мимо, миновавший».

Освобождение еврейского народа из египетского плена, случившееся в воскресенье, – это история, которая в общем смысле рассматривается как освобождение всего человечества от власти греха и смерти.

Праздник Пасхи в православии

Православный праздник Пасхи стали отмечать позднее. Христиане празднуют день Воскресения Сына Божьего, который ради спасения всего человечества отдал себя в жертву.

Традиционный православный праздник Пасхи считается одним из главных в году. В этот день люди празднуют воскресение Спасителя, которое случилось на третий день после его смерти – распятии на кресте. В России этот христианский праздник отмечают широко и торжественно. История праздника Пасхи в нашей стране началась в конце 9 века с приходом христианства из Византии и крещением населения Руси. В 2021 году праздник Пасхи будет отмечаться в первое воскресенье мая – 2 числа.

Иисус Христос был послан Богом на землю для нашего спасения от грехов, от свершения плохих поступков. Он учил людей своим примером – добротой, справедливостью, самопожертвованием. Однако религиозные лидеры испугались того, что Иисус Христос станет правителем всего мира и казнили его – распяли на кресте. Это случилось в пятницу. В это время земля содрогнулась и посыпались камни со скал и гор. Для людей это был самый грустный и скорбный день. Сегодня этот день называют Страстной пятницей.

После казни Христа его ученики сняли его тело с креста и положили в пещеру, закрыв вход в нее огромным камнем. В воскресенье женщины пришли к пещере и увидели, что вход в нее открыт. Ангел сообщил им радостную новость о чудесном воскресении Христа – он стал бессмертным.

От этого события пошло название дня недели воскресенья. Кстати, раньше Воскресенье Христово праздновали еженедельно. Причем в пятницу было принято скорбеть и поститься, а в последний, святой день недели, разрешалось веселиться. В христианских традициях по сей день принято посвящать последний день недели молитвам и отдыху.

Чудесное воскресение Христа означает величайшую победу добра над злом, зримый символ того, что любовь и вера гораздо сильнее, чем ненависть и страх. И как еврейский народ приносит в жертву пасхального ягненка, так и сам Господь принес сына своего на заклание. И в этом событии проявилась безграничная любовь Бога к человеку.

Суть праздника Пасхи

В наше время люди отмечают праздник Пасхи, вспоминая о подвиге Иисуса Христа. Верующие поздравляют друг друга с тем, что Христос воскрес. Для христиан праздник означает переход от смерти к вечной жизни со Христом – от земли к небу, что возглашают и пасхальные песнопения: «Пасха, Господня Пасха! От смерти бо к жизни, и от земли к небеси Христос Бог нас преведе, победную поющия».

Воскресение Иисуса Христа открыло славу Его Божества, скрытую до этого под покровом унижения: позорной и страшной смерти на кресте рядом с распятыми преступниками и разбойниками. Своим Воскресением Иисус Христос благословил и утвердил воскресение для всех людей.

В православии статус Пасхи как главного праздника отражают слова «праздников праздник и торжество из торжеств». Церковное празднование Пасхи продолжается 40 дней. Сегодня для большинства людей Пасха – светлый праздник, символизирующий возрождение и обновление. Суть праздника Пасхи заключается еще и в особой подготовке – последовательному соблюдению ряда религиозных предписаний, которые регламентируют жизнь верующего человека.

Подготовка к Пасхе: православные пасхальные обряды

В восточно-православном христианстве духовная подготовка к Пасхе начинается с Великого поста, 40 дней самопроверки и поста (включая воскресенья), который начинается в Чистый понедельник и завершается в Лазарскую субботу.

Чистый понедельник выпадает за семь недель до пасхального воскресенья. Термин «Чистый понедельник» относится к очищению от греховных отношений посредством поста. Отцы ранней церкви сравнивали пост поста с духовным путешествием души по пустыне мира. Духовный пост призван укрепить внутреннюю жизнь поклоняющегося, ослабляя влечение плоти и приближая его или ее к Богу. Во многих православных церквях постный пост по-прежнему соблюдается со значительной строгостью, что означает, что мясо не употребляется, продукты животного происхождения (яйца, молоко, масло, сыр) не употребляются, а рыба – только в определенные дни.

Лазарская суббота наступает за восемь дней до пасхального воскресенья и знаменует конец Великого поста.

Затем следует Вербное воскресенье, за неделю до Пасхи, в ознаменование триумфального въезда Иисуса Христа в Иерусалим, за которой следует Страстная неделя, которая заканчивается в Пасхальное воскресенье, или Пасху.

Пост продолжается всю Страстную неделю. Многие православные церкви соблюдают пасхальное бдение, которое заканчивается незадолго до полуночи в Великую субботу (или Великую субботу), последний день Страстной недели вечером перед Пасхой. Во время пасхального бдения серия из 15 чтений Ветхого Завета начинается со слов: «В начале сотворил Бог небо и землю». Часто православные церкви отмечают субботний вечер шествием при свечах возле церкви.

Сразу после пасхального бдения пасхальные праздники начинаются с пасхальной утрени в полночь, пасхальных часов и пасхальной Божественной литургии. Пасхальная утреня – это ранняя утренняя молитва или, в некоторых традициях, часть всенощного молитвенного бдения. Обычно это происходит со звоном колокольчиков. Все прихожане обмениваются «поцелуем мира» в конце пасхальной заутреницы. Обычай целоваться основан в следующих местах Священного Писания: Римлянам 16:16; 1 Коринфянам 16:20; 2 Коринфянам 13:12; 1 Фессалоникийцам 5:26; и 1 Петра 5:14.

Пасхальные часы – это краткое молитвенное служение с песнопениями, отражающее пасхальную радость. А Пасхальная Божественная литургия – это причастие или евхаристическое служение. Это первые празднования воскресения Христа, которые считаются наиболее важными службами церковного года.

После евхаристического служения пост прерывается и начинается пир. День православной Пасхи отмечается с большой радостью. Дата события уникальна для каждого года. Праздник Пасхи в 2021 году пройдет 2 мая.

Традиции и приветствия

Пасха, как и Рождество, накопила множество традиций, некоторые из которых не имеют ничего общего с христианским празднованием Воскресения, а происходят от народных обычаев. Обычай пасхального ягненка соответствует как названию Иисуса в Писании («вот агнец Божий, берущий грехи мира», Иоанна 1:29), так и роли агнца как жертвенного животного в древнем Израиле. В древности христиане клали мясо ягненка под жертвенник, благословляли его и затем ели на Пасху. С 12 века постный пост заканчивался на Пасху едой, включающей яйца, ветчину, сыры, хлеб и сладости, которые были благословлены по этому случаю.

Со временем у православных славян возникли все новые и новые поверья, ритуалы, обычаи. Многие приурочены Страстной неделе (Страстной седмице), предшествующей Великому дню Светлого Христова Воскресения – в это время ведется подготовка к Пасхе.

В Чистый четверг до восхода солнца купались в проруби, реке или в бане – в этот день причащались и принимали таинство, убирали в избе, белили печи, ремонтировали ограды, приводили в порядок колодцы, а в Средней полосе России и на Севере окуривали жилища и хлева ветвями можжевельника. Можжевеловый дым считался целебным: люди верили, что он защищает близких и «животинку» от болезней и всякой нечисти. В Чистый четверг освящали соль и ставили ее на стол рядом с хлебом, пекли куличи, пасхальную бабу, медовые пряники, варили овсяный кисель, чтобы задобрить мороз.

Еще одним символом праздника Пасхи стал Благодатный огонь – самовозгорающееся пламя на Гробу Господнем, которое затем выносят к людям священники, а патриарх зажигает им лампады и свечи, символизируя тем самым чудо воскрешения Иисуса Христа и его выхода из могилы. Огонь, или Свет, появляется в процессе проведения особого ритуала, приуроченного к празднованию Пасхи.

Среди православных христиан принято приветствовать друг друга в пасхальный сезон пасхальным приветствием. Приветствие начинается с фразы: «Христос Воскрес!» Ответ: «Воистину, Он воскрес!» Фраза «Христос Анести» (по-гречески «Христос Воскрес») также является названием традиционного православного пасхального гимна, исполняемого во время пасхальных служб в честь воскресения Иисуса Христа.

Важную роль в праздновании Пасхи играют яйца. В православной традиции яйца – символ новой жизни. Ранние христиане использовали яйца, чтобы символизировать воскресение Иисуса Христа и возрождение верующих.

История гласит, что Мария Магдалина, одна из женщин, узнавших в числе первых, что Христос воскрес, решила сообщить римскому императору Тиберию об этом чуде. Она подарила императору яйцо, которое символизировало чудо воскрешения Спасителя. Но император не поверил этому и сказал Марии: «Скорее это яйцо станет красным, чем я поверю в то, что Иисус воскрес». Яйцо тут же стало красным… С тех пор появилась пасхальная традиция красить яйца в красный цвет, чтобы символизировать кровь Иисуса, пролитую на кресте для искупления всех людей. Потом их стали окрашивать и в другие цвета. Каждый цвет, которым мы красим пасхальные яйца, имеет особое значение. Таким образом, красный символизирует кровь Иисуса, синий – символ истины, а зеленый олицетворяет плодородие.

Также в день православного праздника Пасхи принято христосоваться — поздравлять друг друга с великим праздником и обмениваться крашеными яйцами, как символом жизни, трижды целуя друг друга. У славян популярны яичные бои за пасхальной трапезой, или «битье» яйцами. Это простая игра: кто-то держит яйцо носиком вверх, а «соперник» бьет его носиком другого яйца. У кого скорлупа не треснула, тот продолжает «биться» с другим человеком.

Православная пасхальная еда

Страстная неделя в большинстве русских домов очень насыщенная – ведется подготовка к Пасхе. После генеральной уборки приходит пора печь пасхальный хлеб. Яйца расписываются в Святой («Чистый») четверг, а свежие пасхальные куличи (Пасха) готовятся в субботу. Это тяжелое время, поскольку суббота – последний день поста, когда ортодоксальным христианам разрешается есть очень мало. Также запрещено пробовать еду во время приготовления. Но все с нетерпением ждут застолья, и повара стараются. Существует также традиция благословлять пасхальные яйца и хлеб в церкви. Пост заканчивается после пасхальной мессы и начала пиршества.

День Пасхи начинается с долгого семейного завтрака. Стол украшен живыми цветами, ветками вербы и, конечно же, крашеными яйцами. Помимо особых пасхальных блюд, таких как кулич и творожная пасха, которые едят только на праздник Пасхи, на столе много другой еды, такой как сосиски, бекон, сыр, молоко и т. д. – в основном все то, что было запрещено во время сорокадневного поста, а также традиционные лакомства русской кухни. В начале Пасхальной трапезы принято вкушать освященную в храме пищу, затем уже все остальные блюда.

Делить еду на Пасху – давняя традиция в России. Поэтому после завтрака люди ходят в гости к своим друзьям и соседям, обмениваются яйцами и пасхальными хлебцами. Если первое яйцо, которое вы получите на Пасху, действительно является подарком от души, оно никогда не испортится, – гласит старинная русская мудрость.

Пасхальное богослужение

В Страстную седмицу, которая предшествует Пасхе, православные верующие совершают церковные богослужения и вспоминают о страданиях Спасителя. Для христиан этот период из семи дней является особо почитаемым: соблюдается строжайший пост, и начинается подготовка к Пасхе.

Страстная неделя завершается великим и одним из важнейших церковных православных праздников – Пасхой. В этот день все христиане должны присутствовать на церковном богослужении, которое начнется в полночь и заканчивается на рассвете. Под конец торжественной службы священники разносят по храму Священный огонь. Верующие берут его с собой и несут к дому, стараясь не погасить его. Лампадку с огнем ставят во главе стола и стараются поддерживать его в течении года, до следующего праздника Воскресенья.

Кроме этого, главным обрядом считается освящение. По завершении богослужения люди собираются вокруг церкви, чтобы освятить пасхальные корзинки с куличами, яйцами и мясом.

Фото: pixabay.com, pexels.com

Русская Православная Церковь

-

23 Декабрь 2022

26 декабря, в понедельник, в 19.00 в Лектории на Воробьевых горах храма Троицы и МГУ, к 100-летию СССР состоится выступление Михаил а Борисович а С МОЛИНА , историк а русской консервативной мысли, кандидат а исторических наук, директор а Фонда «Имперское возрождение» , по теме «Учреждение СССР — уничтож ение историческ ой Росси и » .

Адрес: Косыгина, 30.

Проезд: от м.Октябрьская, Ленинский проспект, Ломоносовский проспект, Киевская маршрут№297 до ост. Смотровая площадка. -

28 Ноябрь 2022

- Все новости

Приблизительное время чтения: 9 мин.

Ранее весеннее утро 33 года по Р. Х.

Солнце пока не взошло, Иерусалим еще спит после торжественного празднования первого дня Пасхи. Всеобщую радость одного из главных иудейских праздников не могли разделить только ученики Иисуса из Назарета, пришедшие в это утро на гроб своего Учителя, распятого 3 дня назад. Они были почти уверены, что Иисус и есть Тот Самый обещанный Богом Израилю Мессия-Избавитель, но сейчас для них, казалось, уже все было потеряно, ведь мертвые не воскресают…

Немного позднее апостол Павел скажет: «Если Христос не воскрес, то и проповедь наша тщетна, тщетна и вера ваша» (1 Кор 15:14). И, по сути, вся 2000-летняя история христианства — это проповедь события, которое произошло в то весеннее утро, а день Воскресения Иисуса Христа сразу же стал главным праздником христиан.

Хотя началось все значительно раньше…

Исход и его празднование

Само слово «Пасха» (евр. — «Песах») происходит от глагола «проходить» со значением «избавлять», «щадить».

Пасха — это реальное историческое событие, произошедшее в Египте в XIII веке до Р. Х., когда, согласно Преданию, Ангел Господень прошел мимо окропленных кровью жертвенного ягненка еврейских домов и поразил смертью всех египетских первенцев.

Дело в том, что несколько столетий перед этим событием еврейский народ находился в рабстве у египтян. На неоднократные просьбы израильтян отпустить их фараон отвечал неизменным отказом. В последние десятилетия рабства их положение значительно ухудшилось. Египетские власти, обеспокоенные «чрезмерной» численностью евреев, повелели умерщвлять всех рождавшихся у них мальчиков.

Вождь израильского народа — пророк Моисей — по повелению Божьему пытался вразумить упрямого фараона и добиться освобождения. С этим связаны так называемые «10 египетских казней», когда весь Египет (за исключением того места, где жили евреи) поочередно страдал от нашествия жаб, мошек, ядовитых мух, саранчи, моровой язвы и т. д.

Это были явные знамения присутствия Бога среди евреев, однако фараон не сдавался и не отпускал бесплатную рабочую силу. Тогда в Египте произошла последняя, десятая казнь. Бог через Моисея повелел каждой еврейской семье заколоть агнца (однолетнего ягненка или козленка мужского пола), запечь его и съесть с пресным хлебом и горькими травами. Трапеза происходила вечером, есть необходимо было стоя и с великой поспешностью, потому что Бог обещал, что ночью евреи выйдут из Египта. Кровью агнца следовало помазать косяк двери своего жилища. Это был знак для ангела, который умертвил всех египетских первенцев, от первенца семьи фараона до первенцев скота, но прошел мимо тех домов, двери которых были помазаны кровью агнца.

После этой казни испуганный фараон в ту же ночь отпустил евреев из Египта. С тех пор Пасха празднуется израильтянами как день избавления исхода из египетского рабства и спасения от смерти всех еврейских первенцев.

Однако празднование проходило не один день, а семь. Эти дни каждый правоверный иудей должен был провести в Иерусалиме. На время праздника из домов выносились все квасные продукты, и хлеб в пищу употреблялся только пресный (маца), в воспоминание о том, что выход евреев из Египта был таким поспешным, что они не успели заквасить хлеб и взяли с собой только пресные лепешки. Отсюда второе название Пасхи — Праздник Опресноков.

Каждая семья приносила в Храм агнца, которого закалывали там по специально описанному в Моисеевом законе обряду. По словам иудейского историка Иосифа Флавия, на Пасху 70 года по Р. Х. в Иерусалимском Храме было заклано 265 500 агнцев. Возможно, эта цифра сильно преувеличена, как часто бывает у Флавия, но даже если уменьшить ее на несколько порядков, картина того, что происходило в этот день в Храме, впечатляет.