From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Independence Day | |

|---|---|

Displays of fireworks, such as these over the Washington Monument in 1986, take place across the United States on Independence Day. |

|

| Also called | The Fourth of July |

| Observed by | United States |

| Type | National |

| Significance | The day in 1776 that the Declaration of Independence was adopted by the Continental Congress |

| Celebrations | Fireworks, family reunions, concerts, barbecues, picnics, parades, baseball games |

| Date | July 4[a] |

| Frequency | Annual |

Independence Day (colloquially the Fourth of July) is a federal holiday in the United States commemorating the Declaration of Independence, which was ratified by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, establishing the United States of America.

The Founding Father delegates of the Second Continental Congress declared that the Thirteen Colonies were no longer subject (and subordinate) to the monarch of Britain, King George III, and were now united, free, and independent states.[1] The Congress voted to approve independence by passing the Lee Resolution on July 2 and adopted the Declaration of Independence two days later, on July 4.[1]

Independence Day is commonly associated with fireworks, parades, barbecues, carnivals, fairs, picnics, concerts,[2] baseball games, family reunions, political speeches, and ceremonies, in addition to various other public and private events celebrating the history, government, and traditions of the United States. Independence Day is the national day of the United States.[3][4][5]

Background

During the American Revolution, the legal separation of the thirteen colonies from Great Britain in 1776 actually occurred on July 2, when the Second Continental Congress voted to approve a resolution of independence that had been proposed in June by Richard Henry Lee of Virginia declaring the United States independent from Great Britain’s rule.[6][7] After voting for independence, Congress turned its attention to the Declaration of Independence, a statement explaining this decision, which had been prepared by a Committee of Five, with Thomas Jefferson as its principal author. Congress debated and revised the wording of the Declaration to remove its vigorous denunciation of the slave trade, finally approving it two days later on July 4. A day earlier, John Adams had written to his wife Abigail:

The second day of July 1776, will be the most memorable epoch in the history of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival. It ought to be commemorated as the day of deliverance, by solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illuminations, from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward forever more.[8]

Adams’s prediction was off by two days. From the outset, Americans celebrated independence on July 4, the date shown on the much-publicized Declaration of Independence, rather than on July 2, the date the resolution of independence was approved in a closed session of Congress.[9]

Historians have long disputed whether members of Congress signed the Declaration of Independence on July 4, even though Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin all later wrote that they had signed it on that day. Most historians have concluded that the Declaration was signed nearly a month after its adoption, on August 2, 1776, and not on July 4 as is commonly believed.[10][11][12][13][14]

By a remarkable coincidence, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, the only two signatories of the Declaration of Independence later to serve as presidents of the United States, both died on the same day: July 4, 1826, which was the 50th anniversary of the Declaration, Jefferson even mentioning the fact.[15] Although not a signatory of the Declaration of Independence, James Monroe, another Founding Father who was elected president, also died on July 4, 1831, making him the third President who died on the anniversary of independence.[16] The only U.S. president to have been born on Independence Day was Calvin Coolidge, who was born on July 4, 1872.[17]

Observance

- In 1777, thirteen gunshots were fired in salute, once at morning and once again as evening fell, on July 4 in Bristol, Rhode Island. An article in the July 18, 1777 issue of The Virginia Gazette noted a celebration in Philadelphia in a manner a modern American would find familiar: an official dinner for the Continental Congress, toasts, 13-gun salutes, speeches, prayers, music, parades, troop reviews, and fireworks. Ships in port were decked with red, white, and blue bunting.[18]

- In 1778, from his headquarters at Ross Hall, near New Brunswick, New Jersey, General George Washington marked July 4 with a double ration of rum for his soldiers and an artillery salute (feu de joie). Across the Atlantic Ocean, ambassadors John Adams and Benjamin Franklin held a dinner for their fellow Americans in Paris, France.[19]

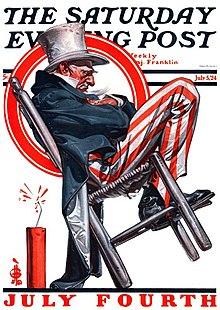

American children of many ethnic backgrounds celebrate noisily in a fantasy 1902 Puck cartoon

- In 1779, July 4 fell on a Sunday. The holiday was celebrated on Monday, July 5.[19]

- In 1781, the Massachusetts General Court became the first state legislature to recognize July 4 as a state celebration.[19][20]

- In 1783, Salem, North Carolina, held a celebration with a challenging music program assembled by Johann Friedrich Peter entitled The Psalm of Joy. The town claims it to be the first public July 4 event, as it was carefully documented by the Moravian Church, and there are no government records of any earlier celebrations.[21]

- In 1870, the U.S. Congress made Independence Day an unpaid holiday for federal employees.[22]

- In 1938, Congress changed Independence Day to a paid federal holiday.[23]

Customs

An 1825 invitation to an Independence Day celebration

Independence Day is a national holiday marked by patriotic displays. Per 5 U.S.C. § 6103, Independence Day is a federal holiday, so all non-essential federal institutions (such as the postal service and federal courts) are closed on that day. While the legal holiday remains on July 4, if that date happens to be on a Saturday or Sunday, then federal government employees will instead take the day off on the adjacent Friday or Monday, respectively.[24]

Families often celebrate Independence Day by hosting or attending a picnic or barbecue;[25] many take advantage of the day off and, in some years, a long weekend to gather with relatives or friends. Decorations (e.g., streamers, balloons, and clothing) are generally colored red, white, and blue, the colors of the American flag. Parades are often held in the morning, before family get-togethers, while fireworks displays occur in the evening after dark at such places as parks, sporting venues, fairgrounds, public shorelines, or town squares.[citation needed]

The night before the Fourth was once the focal point of celebrations, marked by raucous gatherings often incorporating bonfires as their centerpiece. In New England, towns competed to build towering pyramids, assembled from barrels and casks. They were lit at nightfall to usher in the celebration. The highest were in Salem, Massachusetts, with pyramids composed of as many as forty tiers of barrels. These made the tallest bonfires ever recorded. The custom flourished in the 19th and 20th centuries and is still practiced in some New England towns.[26]

Independence Day fireworks are often accompanied by patriotic songs,[27] such as «The Star-Spangled Banner» (the American national anthem); «Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean»; «God Bless America»; «America the Beautiful»; «My Country, ‘Tis of Thee»; «This Land Is Your Land»; «Stars and Stripes Forever»; «Yankee Doodle»; «Dixie» in southern states; «Lift Every Voice and Sing»; and occasionally, but has nominally fallen out of favor, Hail Columbia. Some of the lyrics recall images of the Revolutionary War or the War of 1812.[citation needed]

Firework shows are held in many states,[28] and many fireworks are sold for personal use or as an alternative to a public show. Safety concerns have led some states to ban fireworks or limit the sizes and types allowed. In addition, local and regional conditions may dictate whether the sale or use of fireworks in an area will be allowed; for example, the global supply chain crisis following the COVID-19 pandemic forced cancellations of shows.[29] Some local or regional firework sales are limited or prohibited because of dry weather or other specific concerns.[30] On these occasions the public may be prohibited from purchasing or discharging fireworks, but professional displays (such as those at sports events) may still take place.[citation needed]

A salute of one gun for each state in the United States, called a «salute to the union,» is fired on Independence Day at noon by any capable military base.[31]

New York City has the largest fireworks display in the country sponsored by Macy’s, with more than 22 tons of pyrotechnics exploded in 2009.[32] It generally holds displays in the East River. Other major displays are in Seattle on Lake Union; in San Diego over Mission Bay; in Boston on the Charles River; in Philadelphia over the Philadelphia Museum of Art; in San Francisco over the San Francisco Bay; and on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.[33]

During the annual Windsor–Detroit International Freedom Festival, Detroit, Michigan hosts one of the largest fireworks displays in North America, over the Detroit River, to celebrate Independence Day in conjunction with Windsor, Ontario’s celebration of Canada Day.[34]

The first week of July is typically one of the busiest United States travel periods of the year, as many people use what is often a three-day holiday weekend for extended vacation trips.[35]

Celebration gallery

-

Patriotic trailer shown in theaters celebrating July 4, 1940

-

Fireworks over the National Mall in Washington, D.C. every July 4 are preceded by a concert known as A Capitol Fourth, which takes place outside the U.S. Capitol and is televised on the American public television network PBS.

-

New York City’s fireworks display, shown above over the East Village, is sponsored by Macy’s and is the largest[32] in the country.

-

Towns of all sizes hold celebrations. Shown here is a fireworks display in America’s most eastern town, Lubec, Maine, population 1,300. Canada is across the channel to the right.

-

A festively decorated Independence Day cake

-

Notable celebrations

Originally entitled Yankee Doodle, this is one of several versions of a scene painted by A. M. Willard that came to be known as The Spirit of ’76. Often imitated or parodied, it is a familiar symbol of American patriotism

The 2019 Independence Day parade in Washington, D.C.

- Held since 1785, the Bristol Fourth of July Parade in Bristol, Rhode Island, is the oldest continuous Independence Day celebration in the United States.[36]

- Since 1868, Seward, Nebraska, has held a celebration on the same town square. In 1979 Seward was designated «America’s Official Fourth of July City-Small Town USA» by resolution of Congress. Seward has also been proclaimed «Nebraska’s Official Fourth of July City» by Governor J. James Exon in proclamation. Seward is a town of 6,000 but swells to 40,000+ during the July 4 celebrations.[37]

- Since 1912, the Rebild Society, a Danish-American friendship organization, has held a July 4 weekend festival that serves as a homecoming for Danish-Americans in the Rebild Hills of Denmark.[38]

- Since 1959, the International Freedom Festival is jointly held in Detroit, Michigan, and Windsor, Ontario, during the last week of June each year as a mutual celebration of Independence Day and Canada Day (July 1). It culminates in a large fireworks display over the Detroit River.

- The famous Macy’s fireworks display usually held over the East River in New York City has been televised nationwide on NBC, and locally on WNBC-TV since 1976. In 2009, the fireworks display was returned to the Hudson River for the first time since 2000 to commemorate the 400th anniversary of Henry Hudson’s exploration of that river.[39]

- The Boston Pops Orchestra has hosted a music and fireworks show over the Charles River Esplanade called the «Boston Pops Fireworks Spectacular» annually since 1974.[40] Canons are traditionally fired during the 1812 Overture.[2] The event was broadcast nationally from 1991 until 2002 on A&E, and since 2002 by CBS and its Boston station WBZ-TV. WBZ/1030 and WBZ-TV broadcast the entire event locally, and from 2002 through 2012, CBS broadcast the final hour of the concert nationally in primetime. The national broadcast was put on hiatus beginning in 2013, which Pops executive producer David G. Mugar believed was the result of decreasing viewership caused by NBC’s encore presentation of the Macy’s fireworks.[41][42] The national broadcast was revived for 2016, and expanded to two hours.[43] In 2017, Bloomberg Television took over coverage duty, with WHDH carrying local coverage beginning in 2018.[44]

- On the Capitol lawn in Washington, D.C., A Capitol Fourth, a free concert broadcast live by PBS, NPR and the American Forces Network, precedes the fireworks and attracts over half a million people annually.[45]

Other countries

The Philippines celebrates July 4 as its Republic Day to commemorate the day in 1946 when it ceased to be a U.S. territory and the United States officially recognized Philippine Independence.[46]

July 4 was intentionally chosen by the United States because it corresponds to its Independence Day, and this day was observed in the Philippines as Independence Day until 1962. In 1964, the name of the July 4 holiday was changed to Republic Day.

Rebild National Park in Denmark is said to hold the largest July 4 celebrations outside of the United States.[47]

See also

Notes

- ^ «Federal law (5 U.S.C. 6103) establishes the public holidays . . . for Federal employees. Please note that most Federal employees work on a Monday through Friday schedule. For these employees, when a holiday falls on a nonworkday — Saturday or Sunday — the holiday usually is observed on Monday (if the holiday falls on Sunday) or Friday (if the holiday falls on Saturday).» «Federal Holidays». U.S. Office of Personnel Management. Retrieved January 15, 2022.

References

- ^ a b «What is Independence Day in USA?». Tech Notes. July 2, 2015. Archived from the original on June 22, 2019. Retrieved July 2, 2015.

- ^ a b Hernández, Javier C. (July 3, 2022). «Amid Ukraine War, Orchestras Rethink ‘1812 Overture,’ a July 4 Rite — Some ensembles have decided not to perform Tchaikovsky’s overture, written as commemoration of Russia’s defeat of Napoleon’s army». The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 4, 2022. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- ^ «National Days of Countries». Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. New Zealand. Archived from the original on September 4, 2011. Retrieved June 28, 2009.

- ^ Central Intelligence Agency. «National Holiday». The World Factbook. Archived from the original on May 13, 2009. Retrieved June 28, 2009.

- ^ «National Holiday of Member States». United Nations. Archived from the original on July 2, 2012. Retrieved June 28, 2009.

- ^ Becker, p. 3.

- ^ Staff writer (July 1, 1917). «How Declaration of Independence was Drafted» (PDF). The New York Times. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 4, 2020. Retrieved November 20, 2009.

On the following day, when the formal vote of Congress was taken, the resolutions were approved by twelve Colonies–all except New York. The original Colonies, therefore, became the United States of America on July 2, 1776.

- ^ «Letter from John Adams to Abigail Adams, 3 July 1776, ‘Had a Declaration…’«. Adams Family Papers. Massachusetts Historical Society. Archived from the original on August 6, 2011. Retrieved June 28, 2009.

- ^ Maier, Pauline (August 7, 1997). «Making Sense of the Fourth of July». American Heritage. Archived from the original on September 3, 2019. Retrieved June 28, 2009.

- ^ Burnett, Edward Cody (1941). The Continental Congress. New York: W.W. Norton. pp. 191–96. ISBN 978-1104991852.

- ^ Warren, Charles (July 1945). «Fourth of July Myths». William and Mary Quarterly. 3d. 2 (3): 238–272. doi:10.2307/1921451. JSTOR 1921451.

- ^ «Top 5 Myths About the Fourth of July!». History News Network. George Mason University. June 30, 2001. Archived from the original on July 3, 2009. Retrieved June 28, 2009.

- ^ Becker, pp. 184–85.

- ^ For the minority scholarly argument that the Declaration was signed on July 4, see Wilfred J. Ritz, «The Authentication of the Engrossed Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776» Archived August 18, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Law and History Review 4, no. 1 (Spring 1986): 179–204, via JSTOR.

- ^ Meacham, Jon (2012). Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power. Random House LLC. p. 496. ISBN 978-0679645368.

- ^ «James Monroe – U.S. Presidents». HISTORY.com. Archived from the original on March 23, 2018. Retrieved July 4, 2018.

- ^ Klein, Christopher (July 1, 2015). «8 Famous Figures Born on the Fourth of July». HISTORY.com. Archived from the original on July 4, 2018. Retrieved July 4, 2018.

- ^ Heintze, «The First Celebrations».

- ^ a b c Heintze, «A Chronology of Notable Fourth of July Celebration Occurrences».

- ^ Eiland, Murray (2019). «Heraldry on American Patriotic Postcards». The Armiger’s News. 41 (1): 1–3 – via academia.edu.

- ^ Graff, Michael (November 2012). «Time Stands Still in Old Salem». Our State. Archived from the original on October 4, 2015. Retrieved July 4, 2018.

- ^ Heintze, «How the Fourth of July was Designated as an ‘Official’ Holiday».

- ^ Heintze, «Federal Legislation Establishing the Fourth of July Holiday».

- ^ «Federal Holidays». www.opm.gov. U.S. Office of Personnel Management. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ «Fourth of July no picnic for the nation’s environment». Oak Ridge National Laboratory. July 3, 2003. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

July 4 is by far the most popular day of the year for cookouts, according to a Hearth, Patio & Barbecue Association survey that found that 76 percent of the nation’s grill owners use at least one of their grills that day.

- ^ «The Night Before the Fourth». The Atlantic. July 1, 2011. Archived from the original on October 25, 2011. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- ^ Newell, Shane (July 2, 2018). «Here’s how they pick music for a good Fourth of July fireworks show». The Press-Enterprise. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

Jim Souza, president of the Rialto-based Pyro Spectaculars by Souza, said … ‘Everybody wants patriotic music.’

- ^ Gore, Leada (July 3, 2022). «July 4th: Holiday history, more; Why do we celebrate Independence Day with fireworks?». AL.com. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- ^ Hall, Andy (July 1, 2022). «Which US cities have canceled July 4th fireworks due to fire concerns?». El País. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- ^ Bryant, Kelly (May 19, 2021). «These Are the States Where Fireworks Are Legal». Reader’s Digest.

- ^ «Origin of the 21-Gun Salute». U.S. Army Center of Military History. October 3, 2003. Archived from the original on June 19, 2014. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- ^ a b Biggest fireworks show in U.S. lights up sky Archived July 1, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, USA Today, July 2009.

- ^ Nelson, Samanta (July 1, 2016). «10 of the nation’s Best 4th of July Firework Shows». USA Today. Archived from the original on July 3, 2018. Retrieved July 3, 2018.

- ^ Newman, Stacy. «Freedom Festival». Encyclopedia of Detroit. Detroit Historical Society. Archived from the original on July 3, 2018. Retrieved July 3, 2018.

- ^ «AAA Chicago Projects Increase in Fourth of July Holiday Travelers» Archived October 9, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, PR Newswire, June 23, 2010

- ^ «Founder of America’s Oldest Fourth of July Celebration». First Congregational Church. Archived from the original on March 23, 2014. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

- ^ «History of Seward Nebraska 4th of July». Archived from the original on July 13, 2011.

- ^ «History». Rebild Society. Rebild National Park Society. Archived from the original on July 1, 2009. Retrieved June 30, 2009.

- ^ «2009 Macy’s 4th of July Fireworks». Federated Department Stores. April 29, 2009. Archived from the original on August 25, 2011. Retrieved July 4, 2009.

- ^ «Welcome to Boston’s 4th of July Celebration». Boston 4 Celebrations Foundation. 2009. Archived from the original on August 22, 2008. Retrieved July 4, 2009.

- ^ James H. Burnett III. Boston gets a nonreality show: CBS broadcasts impossible views of 4th fireworks Archived April 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Boston Globe, July 8, 2011

- ^ Powers, Martine; Moskowitz, Eric (June 15, 2013). «July 4 fireworks gala loses its national pop». The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on June 19, 2013. Retrieved June 16, 2013.

- ^ «With CBS on board again, Keith Lockhart is ready to take over prime time». Boston Herald. July 2016. Archived from the original on July 2, 2016. Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ^ «7News partners with Bloomberg TV to air 2018 Boston Pops Fireworks Spectacular». WHDH. June 21, 2018. Archived from the original on June 22, 2018. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ A Capitol Fourth – The Concert Archived February 20, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, PBS, accessed July 12, 2013

- ^ Philippine Republic Day, Official Gazette (Philippines), archived from the original on July 29, 2021, retrieved July 5, 2012

- ^ Lindsey Galloway (July 3, 2012). «Celebrate American independence in Denmark». Archived from the original on November 15, 2014.

Further reading

- Becker, Carl L. (1922). The Declaration of Independence: A Study in the History of Political Ideas. New York: Harcourt, Brace. OCLC 60738220. Retrieved July 4, 2020. Republished: The Declaration of Independence: A Study in the History of Political Ideas. New York: Vintage Books. 1958. ISBN 9780394700601. OCLC 2234953.

- Criblez, Adam (2013). Parading Patriotism: Independence Day Celebrations in the Urban Midwest, 1826–1876. DeKalb, IL, US: Northern Illinois University Press. ISBN 9780875806921. OCLC 1127286749.

- Heintze, James R. «Fourth of July Celebrations Database». American University of Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on August 15, 2000. Retrieved February 10, 2015.

External links

- Fourth of July Is Independence Day USA.gov, July 4, 2014

- U.S. Independence Day a Civic and Social Event U.S. State Department, June 22, 2010

- Fourth of July Orations Collection at the Division of Special Collections, Archives, and Rare Books, Ellis Library, University of Missouri

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Independence Day | |

|---|---|

Displays of fireworks, such as these over the Washington Monument in 1986, take place across the United States on Independence Day. |

|

| Also called | The Fourth of July |

| Observed by | United States |

| Type | National |

| Significance | The day in 1776 that the Declaration of Independence was adopted by the Continental Congress |

| Celebrations | Fireworks, family reunions, concerts, barbecues, picnics, parades, baseball games |

| Date | July 4[a] |

| Frequency | Annual |

Independence Day (colloquially the Fourth of July) is a federal holiday in the United States commemorating the Declaration of Independence, which was ratified by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, establishing the United States of America.

The Founding Father delegates of the Second Continental Congress declared that the Thirteen Colonies were no longer subject (and subordinate) to the monarch of Britain, King George III, and were now united, free, and independent states.[1] The Congress voted to approve independence by passing the Lee Resolution on July 2 and adopted the Declaration of Independence two days later, on July 4.[1]

Independence Day is commonly associated with fireworks, parades, barbecues, carnivals, fairs, picnics, concerts,[2] baseball games, family reunions, political speeches, and ceremonies, in addition to various other public and private events celebrating the history, government, and traditions of the United States. Independence Day is the national day of the United States.[3][4][5]

Background

During the American Revolution, the legal separation of the thirteen colonies from Great Britain in 1776 actually occurred on July 2, when the Second Continental Congress voted to approve a resolution of independence that had been proposed in June by Richard Henry Lee of Virginia declaring the United States independent from Great Britain’s rule.[6][7] After voting for independence, Congress turned its attention to the Declaration of Independence, a statement explaining this decision, which had been prepared by a Committee of Five, with Thomas Jefferson as its principal author. Congress debated and revised the wording of the Declaration to remove its vigorous denunciation of the slave trade, finally approving it two days later on July 4. A day earlier, John Adams had written to his wife Abigail:

The second day of July 1776, will be the most memorable epoch in the history of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival. It ought to be commemorated as the day of deliverance, by solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illuminations, from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward forever more.[8]

Adams’s prediction was off by two days. From the outset, Americans celebrated independence on July 4, the date shown on the much-publicized Declaration of Independence, rather than on July 2, the date the resolution of independence was approved in a closed session of Congress.[9]

Historians have long disputed whether members of Congress signed the Declaration of Independence on July 4, even though Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin all later wrote that they had signed it on that day. Most historians have concluded that the Declaration was signed nearly a month after its adoption, on August 2, 1776, and not on July 4 as is commonly believed.[10][11][12][13][14]

By a remarkable coincidence, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, the only two signatories of the Declaration of Independence later to serve as presidents of the United States, both died on the same day: July 4, 1826, which was the 50th anniversary of the Declaration, Jefferson even mentioning the fact.[15] Although not a signatory of the Declaration of Independence, James Monroe, another Founding Father who was elected president, also died on July 4, 1831, making him the third President who died on the anniversary of independence.[16] The only U.S. president to have been born on Independence Day was Calvin Coolidge, who was born on July 4, 1872.[17]

Observance

- In 1777, thirteen gunshots were fired in salute, once at morning and once again as evening fell, on July 4 in Bristol, Rhode Island. An article in the July 18, 1777 issue of The Virginia Gazette noted a celebration in Philadelphia in a manner a modern American would find familiar: an official dinner for the Continental Congress, toasts, 13-gun salutes, speeches, prayers, music, parades, troop reviews, and fireworks. Ships in port were decked with red, white, and blue bunting.[18]

- In 1778, from his headquarters at Ross Hall, near New Brunswick, New Jersey, General George Washington marked July 4 with a double ration of rum for his soldiers and an artillery salute (feu de joie). Across the Atlantic Ocean, ambassadors John Adams and Benjamin Franklin held a dinner for their fellow Americans in Paris, France.[19]

American children of many ethnic backgrounds celebrate noisily in a fantasy 1902 Puck cartoon

- In 1779, July 4 fell on a Sunday. The holiday was celebrated on Monday, July 5.[19]

- In 1781, the Massachusetts General Court became the first state legislature to recognize July 4 as a state celebration.[19][20]

- In 1783, Salem, North Carolina, held a celebration with a challenging music program assembled by Johann Friedrich Peter entitled The Psalm of Joy. The town claims it to be the first public July 4 event, as it was carefully documented by the Moravian Church, and there are no government records of any earlier celebrations.[21]

- In 1870, the U.S. Congress made Independence Day an unpaid holiday for federal employees.[22]

- In 1938, Congress changed Independence Day to a paid federal holiday.[23]

Customs

An 1825 invitation to an Independence Day celebration

Independence Day is a national holiday marked by patriotic displays. Per 5 U.S.C. § 6103, Independence Day is a federal holiday, so all non-essential federal institutions (such as the postal service and federal courts) are closed on that day. While the legal holiday remains on July 4, if that date happens to be on a Saturday or Sunday, then federal government employees will instead take the day off on the adjacent Friday or Monday, respectively.[24]

Families often celebrate Independence Day by hosting or attending a picnic or barbecue;[25] many take advantage of the day off and, in some years, a long weekend to gather with relatives or friends. Decorations (e.g., streamers, balloons, and clothing) are generally colored red, white, and blue, the colors of the American flag. Parades are often held in the morning, before family get-togethers, while fireworks displays occur in the evening after dark at such places as parks, sporting venues, fairgrounds, public shorelines, or town squares.[citation needed]

The night before the Fourth was once the focal point of celebrations, marked by raucous gatherings often incorporating bonfires as their centerpiece. In New England, towns competed to build towering pyramids, assembled from barrels and casks. They were lit at nightfall to usher in the celebration. The highest were in Salem, Massachusetts, with pyramids composed of as many as forty tiers of barrels. These made the tallest bonfires ever recorded. The custom flourished in the 19th and 20th centuries and is still practiced in some New England towns.[26]

Independence Day fireworks are often accompanied by patriotic songs,[27] such as «The Star-Spangled Banner» (the American national anthem); «Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean»; «God Bless America»; «America the Beautiful»; «My Country, ‘Tis of Thee»; «This Land Is Your Land»; «Stars and Stripes Forever»; «Yankee Doodle»; «Dixie» in southern states; «Lift Every Voice and Sing»; and occasionally, but has nominally fallen out of favor, Hail Columbia. Some of the lyrics recall images of the Revolutionary War or the War of 1812.[citation needed]

Firework shows are held in many states,[28] and many fireworks are sold for personal use or as an alternative to a public show. Safety concerns have led some states to ban fireworks or limit the sizes and types allowed. In addition, local and regional conditions may dictate whether the sale or use of fireworks in an area will be allowed; for example, the global supply chain crisis following the COVID-19 pandemic forced cancellations of shows.[29] Some local or regional firework sales are limited or prohibited because of dry weather or other specific concerns.[30] On these occasions the public may be prohibited from purchasing or discharging fireworks, but professional displays (such as those at sports events) may still take place.[citation needed]

A salute of one gun for each state in the United States, called a «salute to the union,» is fired on Independence Day at noon by any capable military base.[31]

New York City has the largest fireworks display in the country sponsored by Macy’s, with more than 22 tons of pyrotechnics exploded in 2009.[32] It generally holds displays in the East River. Other major displays are in Seattle on Lake Union; in San Diego over Mission Bay; in Boston on the Charles River; in Philadelphia over the Philadelphia Museum of Art; in San Francisco over the San Francisco Bay; and on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.[33]

During the annual Windsor–Detroit International Freedom Festival, Detroit, Michigan hosts one of the largest fireworks displays in North America, over the Detroit River, to celebrate Independence Day in conjunction with Windsor, Ontario’s celebration of Canada Day.[34]

The first week of July is typically one of the busiest United States travel periods of the year, as many people use what is often a three-day holiday weekend for extended vacation trips.[35]

Celebration gallery

-

Patriotic trailer shown in theaters celebrating July 4, 1940

-

Fireworks over the National Mall in Washington, D.C. every July 4 are preceded by a concert known as A Capitol Fourth, which takes place outside the U.S. Capitol and is televised on the American public television network PBS.

-

New York City’s fireworks display, shown above over the East Village, is sponsored by Macy’s and is the largest[32] in the country.

-

Towns of all sizes hold celebrations. Shown here is a fireworks display in America’s most eastern town, Lubec, Maine, population 1,300. Canada is across the channel to the right.

-

A festively decorated Independence Day cake

-

Notable celebrations

Originally entitled Yankee Doodle, this is one of several versions of a scene painted by A. M. Willard that came to be known as The Spirit of ’76. Often imitated or parodied, it is a familiar symbol of American patriotism

The 2019 Independence Day parade in Washington, D.C.

- Held since 1785, the Bristol Fourth of July Parade in Bristol, Rhode Island, is the oldest continuous Independence Day celebration in the United States.[36]

- Since 1868, Seward, Nebraska, has held a celebration on the same town square. In 1979 Seward was designated «America’s Official Fourth of July City-Small Town USA» by resolution of Congress. Seward has also been proclaimed «Nebraska’s Official Fourth of July City» by Governor J. James Exon in proclamation. Seward is a town of 6,000 but swells to 40,000+ during the July 4 celebrations.[37]

- Since 1912, the Rebild Society, a Danish-American friendship organization, has held a July 4 weekend festival that serves as a homecoming for Danish-Americans in the Rebild Hills of Denmark.[38]

- Since 1959, the International Freedom Festival is jointly held in Detroit, Michigan, and Windsor, Ontario, during the last week of June each year as a mutual celebration of Independence Day and Canada Day (July 1). It culminates in a large fireworks display over the Detroit River.

- The famous Macy’s fireworks display usually held over the East River in New York City has been televised nationwide on NBC, and locally on WNBC-TV since 1976. In 2009, the fireworks display was returned to the Hudson River for the first time since 2000 to commemorate the 400th anniversary of Henry Hudson’s exploration of that river.[39]

- The Boston Pops Orchestra has hosted a music and fireworks show over the Charles River Esplanade called the «Boston Pops Fireworks Spectacular» annually since 1974.[40] Canons are traditionally fired during the 1812 Overture.[2] The event was broadcast nationally from 1991 until 2002 on A&E, and since 2002 by CBS and its Boston station WBZ-TV. WBZ/1030 and WBZ-TV broadcast the entire event locally, and from 2002 through 2012, CBS broadcast the final hour of the concert nationally in primetime. The national broadcast was put on hiatus beginning in 2013, which Pops executive producer David G. Mugar believed was the result of decreasing viewership caused by NBC’s encore presentation of the Macy’s fireworks.[41][42] The national broadcast was revived for 2016, and expanded to two hours.[43] In 2017, Bloomberg Television took over coverage duty, with WHDH carrying local coverage beginning in 2018.[44]

- On the Capitol lawn in Washington, D.C., A Capitol Fourth, a free concert broadcast live by PBS, NPR and the American Forces Network, precedes the fireworks and attracts over half a million people annually.[45]

Other countries

The Philippines celebrates July 4 as its Republic Day to commemorate the day in 1946 when it ceased to be a U.S. territory and the United States officially recognized Philippine Independence.[46]

July 4 was intentionally chosen by the United States because it corresponds to its Independence Day, and this day was observed in the Philippines as Independence Day until 1962. In 1964, the name of the July 4 holiday was changed to Republic Day.

Rebild National Park in Denmark is said to hold the largest July 4 celebrations outside of the United States.[47]

See also

Notes

- ^ «Federal law (5 U.S.C. 6103) establishes the public holidays . . . for Federal employees. Please note that most Federal employees work on a Monday through Friday schedule. For these employees, when a holiday falls on a nonworkday — Saturday or Sunday — the holiday usually is observed on Monday (if the holiday falls on Sunday) or Friday (if the holiday falls on Saturday).» «Federal Holidays». U.S. Office of Personnel Management. Retrieved January 15, 2022.

References

- ^ a b «What is Independence Day in USA?». Tech Notes. July 2, 2015. Archived from the original on June 22, 2019. Retrieved July 2, 2015.

- ^ a b Hernández, Javier C. (July 3, 2022). «Amid Ukraine War, Orchestras Rethink ‘1812 Overture,’ a July 4 Rite — Some ensembles have decided not to perform Tchaikovsky’s overture, written as commemoration of Russia’s defeat of Napoleon’s army». The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 4, 2022. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- ^ «National Days of Countries». Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. New Zealand. Archived from the original on September 4, 2011. Retrieved June 28, 2009.

- ^ Central Intelligence Agency. «National Holiday». The World Factbook. Archived from the original on May 13, 2009. Retrieved June 28, 2009.

- ^ «National Holiday of Member States». United Nations. Archived from the original on July 2, 2012. Retrieved June 28, 2009.

- ^ Becker, p. 3.

- ^ Staff writer (July 1, 1917). «How Declaration of Independence was Drafted» (PDF). The New York Times. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 4, 2020. Retrieved November 20, 2009.

On the following day, when the formal vote of Congress was taken, the resolutions were approved by twelve Colonies–all except New York. The original Colonies, therefore, became the United States of America on July 2, 1776.

- ^ «Letter from John Adams to Abigail Adams, 3 July 1776, ‘Had a Declaration…’«. Adams Family Papers. Massachusetts Historical Society. Archived from the original on August 6, 2011. Retrieved June 28, 2009.

- ^ Maier, Pauline (August 7, 1997). «Making Sense of the Fourth of July». American Heritage. Archived from the original on September 3, 2019. Retrieved June 28, 2009.

- ^ Burnett, Edward Cody (1941). The Continental Congress. New York: W.W. Norton. pp. 191–96. ISBN 978-1104991852.

- ^ Warren, Charles (July 1945). «Fourth of July Myths». William and Mary Quarterly. 3d. 2 (3): 238–272. doi:10.2307/1921451. JSTOR 1921451.

- ^ «Top 5 Myths About the Fourth of July!». History News Network. George Mason University. June 30, 2001. Archived from the original on July 3, 2009. Retrieved June 28, 2009.

- ^ Becker, pp. 184–85.

- ^ For the minority scholarly argument that the Declaration was signed on July 4, see Wilfred J. Ritz, «The Authentication of the Engrossed Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776» Archived August 18, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Law and History Review 4, no. 1 (Spring 1986): 179–204, via JSTOR.

- ^ Meacham, Jon (2012). Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power. Random House LLC. p. 496. ISBN 978-0679645368.

- ^ «James Monroe – U.S. Presidents». HISTORY.com. Archived from the original on March 23, 2018. Retrieved July 4, 2018.

- ^ Klein, Christopher (July 1, 2015). «8 Famous Figures Born on the Fourth of July». HISTORY.com. Archived from the original on July 4, 2018. Retrieved July 4, 2018.

- ^ Heintze, «The First Celebrations».

- ^ a b c Heintze, «A Chronology of Notable Fourth of July Celebration Occurrences».

- ^ Eiland, Murray (2019). «Heraldry on American Patriotic Postcards». The Armiger’s News. 41 (1): 1–3 – via academia.edu.

- ^ Graff, Michael (November 2012). «Time Stands Still in Old Salem». Our State. Archived from the original on October 4, 2015. Retrieved July 4, 2018.

- ^ Heintze, «How the Fourth of July was Designated as an ‘Official’ Holiday».

- ^ Heintze, «Federal Legislation Establishing the Fourth of July Holiday».

- ^ «Federal Holidays». www.opm.gov. U.S. Office of Personnel Management. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ «Fourth of July no picnic for the nation’s environment». Oak Ridge National Laboratory. July 3, 2003. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

July 4 is by far the most popular day of the year for cookouts, according to a Hearth, Patio & Barbecue Association survey that found that 76 percent of the nation’s grill owners use at least one of their grills that day.

- ^ «The Night Before the Fourth». The Atlantic. July 1, 2011. Archived from the original on October 25, 2011. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- ^ Newell, Shane (July 2, 2018). «Here’s how they pick music for a good Fourth of July fireworks show». The Press-Enterprise. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

Jim Souza, president of the Rialto-based Pyro Spectaculars by Souza, said … ‘Everybody wants patriotic music.’

- ^ Gore, Leada (July 3, 2022). «July 4th: Holiday history, more; Why do we celebrate Independence Day with fireworks?». AL.com. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- ^ Hall, Andy (July 1, 2022). «Which US cities have canceled July 4th fireworks due to fire concerns?». El País. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- ^ Bryant, Kelly (May 19, 2021). «These Are the States Where Fireworks Are Legal». Reader’s Digest.

- ^ «Origin of the 21-Gun Salute». U.S. Army Center of Military History. October 3, 2003. Archived from the original on June 19, 2014. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- ^ a b Biggest fireworks show in U.S. lights up sky Archived July 1, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, USA Today, July 2009.

- ^ Nelson, Samanta (July 1, 2016). «10 of the nation’s Best 4th of July Firework Shows». USA Today. Archived from the original on July 3, 2018. Retrieved July 3, 2018.

- ^ Newman, Stacy. «Freedom Festival». Encyclopedia of Detroit. Detroit Historical Society. Archived from the original on July 3, 2018. Retrieved July 3, 2018.

- ^ «AAA Chicago Projects Increase in Fourth of July Holiday Travelers» Archived October 9, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, PR Newswire, June 23, 2010

- ^ «Founder of America’s Oldest Fourth of July Celebration». First Congregational Church. Archived from the original on March 23, 2014. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

- ^ «History of Seward Nebraska 4th of July». Archived from the original on July 13, 2011.

- ^ «History». Rebild Society. Rebild National Park Society. Archived from the original on July 1, 2009. Retrieved June 30, 2009.

- ^ «2009 Macy’s 4th of July Fireworks». Federated Department Stores. April 29, 2009. Archived from the original on August 25, 2011. Retrieved July 4, 2009.

- ^ «Welcome to Boston’s 4th of July Celebration». Boston 4 Celebrations Foundation. 2009. Archived from the original on August 22, 2008. Retrieved July 4, 2009.

- ^ James H. Burnett III. Boston gets a nonreality show: CBS broadcasts impossible views of 4th fireworks Archived April 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Boston Globe, July 8, 2011

- ^ Powers, Martine; Moskowitz, Eric (June 15, 2013). «July 4 fireworks gala loses its national pop». The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on June 19, 2013. Retrieved June 16, 2013.

- ^ «With CBS on board again, Keith Lockhart is ready to take over prime time». Boston Herald. July 2016. Archived from the original on July 2, 2016. Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ^ «7News partners with Bloomberg TV to air 2018 Boston Pops Fireworks Spectacular». WHDH. June 21, 2018. Archived from the original on June 22, 2018. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ A Capitol Fourth – The Concert Archived February 20, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, PBS, accessed July 12, 2013

- ^ Philippine Republic Day, Official Gazette (Philippines), archived from the original on July 29, 2021, retrieved July 5, 2012

- ^ Lindsey Galloway (July 3, 2012). «Celebrate American independence in Denmark». Archived from the original on November 15, 2014.

Further reading

- Becker, Carl L. (1922). The Declaration of Independence: A Study in the History of Political Ideas. New York: Harcourt, Brace. OCLC 60738220. Retrieved July 4, 2020. Republished: The Declaration of Independence: A Study in the History of Political Ideas. New York: Vintage Books. 1958. ISBN 9780394700601. OCLC 2234953.

- Criblez, Adam (2013). Parading Patriotism: Independence Day Celebrations in the Urban Midwest, 1826–1876. DeKalb, IL, US: Northern Illinois University Press. ISBN 9780875806921. OCLC 1127286749.

- Heintze, James R. «Fourth of July Celebrations Database». American University of Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on August 15, 2000. Retrieved February 10, 2015.

External links

- Fourth of July Is Independence Day USA.gov, July 4, 2014

- U.S. Independence Day a Civic and Social Event U.S. State Department, June 22, 2010

- Fourth of July Orations Collection at the Division of Special Collections, Archives, and Rare Books, Ellis Library, University of Missouri

День независимости (Independence Day) — день принятия Декларации независимости США в 1776 году, которая провозгласила независимость США от Королевства Великобритании — считается днем рождения Соединенных Штатов как свободной и независимой страны. Большинство американцев называют этот праздник просто по его дате — Четвертое июля (Fourth of July).

4 июля 1776 года Конгресс одобрил Декларацию независимости (Declaration of Independence), которую подписали президент Второго Континентального конгресса Джон Хэнкок (John Hancock) и секретарь Континентального Конгресса Чарльз Томсон (Charles Thomson).

В то время жители 13 британских колоний, которые располагались вдоль восточного побережья сегодняшней территории Соединенных Штатов, вели войну с английским королем и парламентом, поскольку считали, что те обращаются с ними несправедливо. Война началась в 1775 году.

День насыщен праздничными мероприятиями (Фото: Maridav, по лицензии Shutterstock.com)

В ходе военных действий колонисты поняли, что сражаются не просто за лучшее обращение, а за свободу от английского владычества. Это было четко сформулировано в Декларации независимости, которую подписали руководители колоний. Впервые в официальном документе колонии именовались Соединенными Штатами Америки.

Празднование в честь даты подписания Декларации независимости началось с первой же годовщины. В 1870 году Конгресс США сделал День Независимости неоплачиваемым праздничным днем для федеральных служащих, а в 1938-м Конгресс изменил статус дня на оплачиваемый федеральный праздник.

В настоящее время национальный праздник Четвертого июля насыщен фейерверками, пикниками и другими мероприятиями на открытом воздухе, а также концертами и патриотическими речами, фестивалями и историческими реконструкциями.

К дружескому празднованию присоединяются и соседние области Канады, а также Гватемала, Филиппины и ряд европейских стран.

В воскресенье Соединенные Штаты Америки отмечают свой главный национальный праздник — День независимости. Считается, что 245 лет назад в этот день Конгресс официально принял основополагающий для Америки документ — Декларацию независимости. Однако 4 июля 1776 года независимость не провозглашалась, уточняет Fox News.

Праздник должен был проходить 2 июля

Второй Континентальный Конгресс фактически проголосовал за независимость на два дня раньше, 2 июля. В письме своей жене Абигейл один из отцов-основателей США Джон Адамс предсказал, что будущие поколения будут отмечать именно 2 июля как День независимости, сказав: «Второй день июля 1776 года будет отмечается последующими поколениями как великий юбилейный фестиваль. С этого времени он должен быть отмечен пышностью и парадом, представлениями, играми, спортом, оружием, колокольчиками, кострами и освещением от одного конца этого континента до другого».

До наших дней дошло 26 копий Декларации

После принятия Декларации независимости «Комитет пяти», в который входили Томас Джефферсон, Джон Адамс, Бенджамин Франклин, Роджер Шерман и Роберт Р. Ливингстон, отвечал за тиражирование утвержденного текста. 5 июля владелец типографии из Филадельфии Джон Данлэп разослал все сделанные им копии для газет в 13 колониях, а также командирам континентальных войск и местным политикам. Первоначально имелись сотни копий, известных как «Данлэпские залпы», но только 26 из них сохранились до нашего времени и в основном выставлены в музейных и библиотечных собраниях. К слову, один из недавно обнаруженных «залпов Данлэпа» был найден жителем Филадельфии на задней стороне рамки для картины, которая была куплена на блошином рынке за 4 доллара в 1989 году.

Когда 9 июля 1776 года один из «Данлэпских залпов» прибыл в Нью-Йорк, Джордж Вашингтон, который в то время был командующим континентальными силами в Нью-Йорке, зачитал этот документ толпе перед зданием мэрии. Многие из них приветствовали Декларации и чуть позже снесли статую британского короля Георга III, находившуюся неподалеку. Позже статуя была переплавлена и использовалась для изготовления десятков тысяч мушкетных ядер для американской армии.

Декларацию спрятали в Форт-Ноксе

После нападения на Перл-Харбор агенту секретной службы США Гарри Нилу было поручено переместить «бесценные исторические документы» — оригиналы Декларации независимости и Конституцию — в безопасное место вдали от Вашингтона, округ Колумбия. После встречи с библиотекарем Арчибальдом Маклишем в Библиотеке Конгресса Нил составил план того, как незаметно перевезти документы из Вашингтона в Форт-Нокс, который находится недалеко от Луисвилля, штат Кентукки. Геттисбергское обращение Авраама Линкольна, Библия Гутенберга и Статьи Конфедерации также хранились в некоторых ящиках в Форт-Ноксе. Декларация была возвращена в Вашингтон, округ Колумбия, в 1944 году.

Что произошло с подписантами?

Некоторые из подписавших Декларацию независимости, такие как Джон Адамс и Томас Джефферсон, посвятили свою жизнь государственной службе, став вторым и третьим президентами Соединенных Штатов. Тем не менее, некоторые из подписантов остались только в истории, такие как Баттон Гвиннетт из Джорджии и Джозиа Бартлетт из Нью-Гэмпшира, чье имя было использовано, с немного другим написанием, в качестве персонажа романа Мартина Шина в «Западном крыле».

Есть и другие факты о подписавших и о том, что произошло после того, как они подписали Декларацию. Пятеро подписантов были захвачены британской армией во время войны за независимость и подверглись пыткам перед смертью. Дома двенадцати подписантов были обысканы и сожжены. У двух подписантов были убиты их сыновья. Девять подписантов умерли от ран или других невзгод до конца войны за независимость. Однако те, кто подписал Декларацию независимости, воспользовались невероятным шансом принять этот документ, который изменил весь мир.

В целом, отмечают эксперты, Декларация стала политическим, во многом, декларативным документом, радикальным в свое время, призванным объединить прогрессивные силы. Конституция, с другой стороны, была очень хорошо продуманным документом, основная цель которого заключалась в предотвращении захвата власти. Вот почему в Конституции большинство полномочий закреплено за штатами, а не за федеральным правительством.

Декларация независимости и Конституция Соединенных Штатов являются двумя из четырех основных законодательных актов Соединенных Штатов, третьим является Постановление о Северо-Западе, а четвертым — Статьи Конфедерации. В этих документах американские отцы-основатели изложили свой взгляд на права человека и власть с видением того, что американцы являются свободными людьми в установленных границах ограниченных полномочий федерального правительства.

История Дня Независимости в США

Четвертое июля, также известное как День Независимости (англ. Independence Day), является праздником в Соединенных Штатах с 1941 года, но традиция празднования Дня Независимости восходит к 18 (!) веку и Американской революции.

2 июля 1776 года Континентальный конгресс проголосовал за независимость, а два дня спустя делегаты приняли Декларацию независимости, исторический документ, разработанный Томасом Джефферсоном, третьим президентом в истории США.

Интересный факт: с этого самого дня 4 июля отмечается как триумфальный праздник американской независимости, с различными активностями, начиная от фейерверков, парадов, концертов и заканчивая более непринужденными семейными посиделками и барбекю.

Является ли День Независимости государственным праздником?

Да, действительно, День Независимости – государственный праздник. Правительственные учреждения штата в этот день закрыты, как и многие школы и предприятия в США.

Празднование Дня Независимости

День Независимости – это день семейных торжеств с пикниками и барбекю, в который большое внимание уделяется американской традиции политической свободы. Мероприятия, связанные с этим днем, включают соревнования по поеданию арбузов или хот-догов и спортивные мероприятия, такие как бейсбольные матчи, гонки, плавание и перетягивание каната.

Многие американцы вывешивают американский флаг перед своими домами или зданиями. Все люди торжественно устраивают фейерверки, которые часто сопровождаются патриотической музыкой. Самые впечатляющие фейерверки показывают по телевидению.

Этот день – абсолютно патриотический праздник, посвященный сильным сторонам Соединенных Штатов. Для американцев День Независимости один из самых громких и несомненно важных праздников. Кроме того, многие политики в этот день появляются на публичных мероприятиях, чтобы продемонстрировать свое уважение истории, наследию и народу своей большой страны. Прежде всего, люди в Соединенных Штатах благодарят за свободу личности и независимость, за которые боролось первое поколение многих сегодняшних американцев.

Кстати, Статуя Свободы (англ. Statue of Liberty) –- это национальный памятник, который ассоциируется именно с Днем независимости.

Даты празднования

Если 4 июля приходится на субботу, то праздник независимости отмечается в пятницу, 3 июля. А если, например, 4 июля приходится на воскресенье, то он отмечается в понедельник, 5 июля.

В этот день американцы по-настоящему отдыхают: приходят на парады, увлекательные шоу в честь праздника и на волшебные фейерверки.

Немного фактов из истории про День Независимости

- В 1775 году жители Новой Англии (региона в США) начали борьбу с англичанами за свою независимость.

- 2 июля 1776 года Конгресс тайно проголосовал за независимость от Великобритании.

- Два дня спустя, 4 июля 1776 года, была утверждена окончательная редакция Декларации независимости, и документ был опубликован.

- Первое публичное чтение Декларации независимости состоялось 8 июля 1776 года.

- В 1870 году День Независимости был объявлен неоплачиваемым праздником для федеральных служащих.

- В 1941 году этот день наконец стал для них оплачиваемым отпуском.

Первое описание того, как будет отмечаться День Независимости, содержится в известном письме Джона Адамса, второго президента США, своей жене Эбигейл от 3 июля 1776 года. Он описал пышность парада с шоу, играми, спортом, кострами и иллюминацией по всей территории Соединенных Штатов. Из этого фрагмента можно понять, что термин «День Независимости» не использовался, вплоть до 1791 года.

Интересный факт: Томас Джефферсон и Джон Адамс, президенты США, оба подписавшие Декларацию независимости, умерли 4 июля 1826 года – ровно через 50 лет после принятия декларации.

Теперь вы знаете всё про легендарный День Независимости!

Happy 4th of July!

| День независимости США | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Фейерверк-шоу у Монумента Вашингтона | |

| Тип | Национальный |

| иначе | Четвёртое июля Славное четвёртое число Четвёртое |

| Значение | В этот день Декларация независимости США была официально принята Вторым Континентальным конгрессом |

| Дата | 4 июля |

| Празднование | Фейерверки, встреча всей семьи, концерты, барбекю, пикники, парады, бейсбольные игры |

День независимости США (англ. Independence Day) — день подписания Декларации независимости США в 1776 году, которая провозглашает независимость США от Королевства Великобритании; празднуется в Соединенных Штатах Америки 4 июля. День независимости считается днём рождения Соединенных Штатов как свободной и независимой страны. Большинство американцев называют этот праздник просто по его дате — «Четвёртое июля». Праздник сопровождается фейерверками, парадами, барбекю, карнавалами, ярмарками, пикниками, концертами, бейсбольными матчами, семейными встречами, обращениями политиков к народу и церемониями, а также другими публичными и частными мероприятиями, традиционными для Соединённых Штатов. День независимости — это национальный праздник США.[1][2][3]

Содержание

- 1 История

- 2 Развитие

- 3 Празднование

- 4 Уникальные или исторические празднования

- 5 День Независимости США в искусстве

- 6 См. также

- 7 Примечания

- 8 Литература

- 9 Ссылки

История

Праздник напоминает о том, что 4 июля 1776 года была принята Декларация Независимости. 2 июля Второй Континентальный конгресс путём голосования одобрил резолюцию независимости, которая в июне была предложена к рассмотрению Ричардом Генри Ли (англ.)русск. от Виргинии.[4][5] В то время жители 13 британских колоний, которые располагались вдоль восточного побережья сегодняшней территории Соединенных Штатов, вели войну с английским королем и парламентом в связи с тем, что Парламент Великобритании в 1764 году выпустил «Закон о валюте». Этот закон запрещал администрации американских колоний эмиссию своих собственных, ничем не обеспеченных и бесконтрольно печатаемых денег и обязал их впредь платить все налоги золотыми и серебряными монетами. Другими словами, закон насильно перевел колонии на золотой стандарт. Началась война в 1775 году. Декларацию о независимости подготовил «Комитет пяти» во главе с Томасом Джефферсоном. Конгресс обсудил и переработал декларацию, приняв её, в итоге, 4 июля. Впервые в официальном документе колонии именовались Соединёнными[6]. Днём ранее, Джон Адамс написал своей жене Абигель:

Второй день июля 1776 года станет самым незабываемым в истории Америки. Я склонен верить, что этот день будет праздноваться последующими поколениями как великое ежегодное торжество. Этот день должен отмечаться как день освобождения с пышностью и парадом, с представлениями, играми, спортивными состязаниями, пушками, звоном колоколов, кострами и украшениями, он должен праздноваться на всём континенте и на протяжении всех времён[7].

Предсказания Адамса разошлись с реальностью всего на два дня. С самого начала, американцы праздновали независимость 4 июля, в день, когда была провозглашена Декларация Независимости. А 2 июля — это дата, когда на закрытом заседании конгресса была утверждена резолюция независимости[8].

Историки вели долгие споры по поводу того, действительно ли Конгресс подписал Декларацию Независимости 4 июля 1776 года, так как Томас Джефферсон, Джон Адамс и Бенджамин Франклин позже написали, что они подписали её в тот день. Большинство историков сделали вывод, что Декларация была подписана спустя месяц после её принятия, то есть 2 августа 1776 года, а не 4 июля как принято считать.[9][10][11][12][13]

По удивительному стечению обстоятельств, Джон Адамс и Томас Джефферсон, оба участвовавшие в подписании Декларации Независимости, позже стали президентами Соединённых Штатов Америки и умерли в один день: 4 июля 1826 года, когда отмечался 50-летний юбилей принятия Декларации. Хотя и не участвовавший в подписании Декларации Независимости Джеймс Монро, пятый президент США, также умер 4 июля 1831 года. Калвин Куллидж, тридцатый президент, родился 4 июля 1872 года и, таким образом, до сих пор остаётся единственным президентом, родившимся в День Независимости.

Развитие

- В 1777 году 4 июля в Бристоле (Род-Айленд) (англ.)русск. было произведено 13 выстрелов — первый раз утром и затем ещё раз вечером. Филадельфия отмечала первую годовщину почти так же, как современные американцы: церемониальный ужин в честь Континентального Конгресса, тосты, салюты из тринадцати выстрелов, выступления, молитвы, музыка, парады, военные смотры и фейерверки. Корабли украшались красными, белыми и голубыми парусами[14].

- В 1778 году генерал Джордж Вашингтон отметил 4 июля с двойной порцией рома в честь своих солдат и артиллерийским салютом. С другой стороны Атлантического океана в Париже послы Джон Адамс и Бенджамин Франклин провели торжественный ужин в честь своих собратьев американцев[15].

К сожалению, в вашем браузере отключён JavaScript, или не имеется требуемого проигрывателя.

Вы можете загрузить ролик или загрузить проигрыватель для воспроизведения ролика в браузере.

Патриотический ролик, показанный в театрах накануне четвёртого июля 1940 года.

- В 1779 году 4 июля выпало на воскресенье. Праздник отмечался в понедельник, 5 июля[15]

- В 1781 году Массачусетский генеральный совет стал первым законодательным собранием штата, официально признанным 4 июля[15]

- В 1783 году Моравская церковь в городе Уинстон-Сейлем отпраздновала 4 июля сложной музыкальной программой, составленной Иоганном Фридрихом Петером. Эта работа была названа «The Psalm of Joy»[15].

- В 1791 году впервые было использовано название «День независимости»[15].

- В 1820 году четвёртое июля было впервые отпраздновано в городе Истпорт (штат Мэн), который на тот момент был самым большим городом в штате[16].

- В 1870 году Конгресс США сделал День Независимости неоплачиваемым праздничным днём для федеральных служащих[17].

- В 1938 году Конгресс изменил статус Дня Независимости на оплачиваемый федеральный праздник[18].

Празднование

В дополнение к фейерверк-шоу — патриотические красные, белые и голубые огни одного из самых высоких зданий в Майами.

День Независимости — это национальный праздник, сопровождающийся патриотическими представлениями. Подобно другим летним торжествам, День Независимости чаще всего празднуется на открытом воздухе. День Независимости является федеральным праздником, поэтому все не очень важные федеральные институты (такие как Почтовая служба США и Федеральный суд США) не работают в этот день. Многие политики поднимают свой рейтинг в этот день, выступая на публичных мероприятиях, восхваляя наследие, законы, историю, общество и людей своей страны.

Семьи часто празднуют День Независимости, устраивая пикники или барбекю с друзьями, если это один выходной, либо, в некоторые годы, когда 4 июля выпадает на субботу или воскресенье, а поэтому переносится на ближайший понедельник, собираются на длинный уикенд со своей роднёй. Украшения (например, ленты и шары), как правило, красные, белые и голубые — цвета американского флага. Парады чаще всего проводятся утром, в то время как фейерверки устраиваются вечером в парках, на ярмарочных или городских площадях.

Нью-Йоркское фейерверк-шоу, показанное над крышами East Village и финансировавшееся сетью универмагов Macy’s — крупнейшее фейерверк-шоу[19] в стране.

Фейерверки часто сопровождаются патриотическими песнями, например национальным гимном «Знамя, усыпанное звёздами», «Боже, храни Америку», «Америка прекрасная», «Америка», «Эта земля — твоя земля», «Звёзды и полосы навечно». Некоторые песни поют только на определённых территориях, например, «Янки-дудл» в северо-восточных штатах или «Дикси» в южных штатах. Иногда вспоминают песни о Войне за независимость или Англо-американской войне 1812 года[20].

Праздничные фейерверки проходят во многих штатах в виде публичных шоу. Также, многие американцы самостоятельно устраивают шоу с фейерверками на свои деньги. Из соображений безопасности некоторые штаты запретили самостоятельно устраивать фейерверки или ограничили перечень разрешённых размеров и видов[21].

Салют из первой пушки в каждом штате называется «салютом единства» — выстрел производится 4 июля в полдень на любой военной базе, где есть артиллерия в рабочем состоянии[22].

В 2009 году в Нью-Йорке прошло крупнейшее фейерверк-шоу в стране, во время которого было израсходовано 22 тонны пиротехники[19]. Другие известные крупные фейерверки были проведены в Чикаго на озере Мичиган; в Сан-Диего у залива Mission; в Бостоне на реке Чарльз; в Сент-Луисе на реке Миссисипи; в Сан-Франциско у залива Сан-Франциско; и на Национальной аллее в Вашингтоне[23].

Столовое украшение для вечеринки четвёртого июля

Во время ежегодного Международного фестиваля свободы в Детройте организовывается одно из крупнейших фейерверк-шоу в мире, которое проходит на берегу реки Детройт во время празднования Дня Независимости вместе с городом Уинсор (Онтарио), празднующим День Канады.

Несмотря на то, что официальная церемония всегда проводится 4 июля, степень празднования может варьироваться в зависимости от того, на какой день недели выпало четвёртое июля. Если праздник выпал на середину недели, то некоторые фейерверки и торжества могут быть перенесены на выходные для удобства.

В первую неделю июля американцы начинают активно путешествовать по стране, так как многие люди используют праздник для того, чтобы уехать куда-нибудь в отпуск[24].

Уникальные или исторические празднования

- Впервые проведённый в 1785 году парад в честь 4 июля в Бристоле является старейшим непрерывным празднованием Дня Независимости в Соединённых Штатах[25].

- В 1912 году Ребилльское датско-американское сообщество впервые отпраздновало четвёртое июля, что послужило созданию коммуны Ребилль в Дании[26].

- В 1916 году Nathan’s Hot Dog Eating Contest в Кони-Айленде, Бруклине, Нью-Йорке предположительно стартовал как способ разрешения спора между четырьмя иммигрантами, которые не могли выяснить, кто из них бо́льший патриот. Таким образом, с 1916 года существует традиция по проведению в День Независимости чемпионата по поеданию хот-догов в Нью-Йорке и других городах[27].

Гулянье в День Независимости на берегу озера Мичиган

- Начиная с 1959 года Международный фестиваль свободы совместно проводится Детройтом (Мичиган) и Уинсором (Онтарио) в течение последней недели июня каждый год как совместное празднование Дня Независимости и Дня Канады (1 июля). Фестиваль заканчивается грандиозным фейерверком у реки Детройт[28].

- В День Независимости играется множество матчей в главной и низшей бейсбольных лигах[29].

- Знаменитое фейерверк-шоу сети универмагов Macy’s обычно проводится у пролива Ист-Ривер в Нью-Йорке и транслируется на канале NBC, начиная с 1976 года. В 2009 году шоу было перенесено к реке Гудзон для первого, начиная с 2000 года, празднования 400-летнего юбилея открытия этой реки Генри Гудзоном[30].

- Начиная с 1970 года, ежегодный 10-километровый забег Peachtree Road Race проводится в Атланте, штат Джорджия[31].

- Бостонский оркестр устраивает музыкальное шоу с фейерверком, названное «Boston Pops Fireworks Spectacular» и проходящее у реки Чарльз ежегодно, начиная с 1973 года. Представление показывалось на всю страну с 1987 по 2002 года на телеканале A&E Network, а с 2003 года шоу начали транслировать на телеканале CBS[32].

- На газоне около Капитолия в Вашингтоне проходит бесплатный концерт «A Capitol Fourth», который предшествует фейерверкам и привлекает около полумиллиона человек каждый год[33].

День Независимости США в искусстве

Одним из самых известных фильмов, в сюжете которого важное значение имеет американский День Независимости, является вышедшая в 1996 году картина Роланда Эммериха «День Независимости» с Уиллом Смитом в главной роли. По сюжету, на Землю нападают инопланетные захватчики и начинают уничтожать крупнейшие города. Но люди побеждают агрессоров из космоса. Таким образом, День независимости США становится днём независимости всей Земли.

Совсем не таким патриотичным является вышедший в 1989 году фильм Оливера Стоуна «Рождённый четвёртого июля», где в главной роли снялся Том Круз. Фильм рассказывает реальную историю Рона Ковика. Рон родился 4 июля — в День Независимости США. Он рос в атмосфере гордости за свою страну. Отправился во Вьетнам защищать интересы Америки. Там он столкнулся с настоящей войной, трагедией и ужасом, потерял товарища, сам получил тяжёлое ранение. В госпитале он обнаружил наплевательское отношение к себе. Вернувшись к мирной жизни, он начинает чувствовать, что его идеалы и иллюзии разрушаются, что правительство бросило и подставило его во Вьетнаме, навсегда испортив его жизнь из-за малопонятных международных амбиций. Рон превращается в агрессивного психопата и алкоголика. Но после некоторого времени он решает присоединиться к антивоенному движению ветеранов — священная борьба за мир снова возвращает его к жизни.

В 1995 году Ричард Форд (англ.)русск. написал роман «День независимости» (англ.)русск., который был продолжением его же романа «Спортивный журналист» (англ.)русск., написанного в 1986 году. Произведение получило Пулитцеровскую премию за художественную книгу в 1996 году. Роман рассказывает о Фрэнке Баскомбе — реальном агенте по продаже недвижимости из Нью-Джерси. В День Независимости он навещает свою бывшую жену, сына, любовницу, съёмщиков одного из своих домов и некоторых своих клиентов, которые испытывают затруднения в поисках хорошего дома. Роман «День независимости» — пасторальное размышление о человеке, достигшего среднего возраста и оценивающего своё место в жизни и в мире.

См. также

- День нации

Примечания

- ↑ National Days of Countries. Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. New Zealand. Архивировано из первоисточника 25 августа 2011. Проверено 28 июня 2009.

- ↑ National Holiday. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Проверено 28 июня 2009.

- ↑ National Holiday of Member States. United Nations. Архивировано из первоисточника 25 августа 2011. Проверено 28 июня 2009.

- ↑ Becker Carl L. The Declaration of Independence: A Study in the History of Political Ideas. — Нью-Йорк: Harcourt, Brace, 1922. — С. 3.

- ↑ Staff writer.. How Declaration of Independence was Drafted (PDF), New York Times (1 июля 1917). Проверено 20 ноября 2009. «На следующий день, когда формальное голосование Конгресса было завершено, резолюции были приняты двенадцатью колониями–кроме Нью-Йорка. Колонии, вследствие этого, стали Соединёнными Штатами Америки 2 июля 1776 года.».

- ↑ Декларация Независимости (рус.). Историк.ру. Архивировано из первоисточника 25 августа 2011. Проверено 7 ноября 2010.

- ↑ Letter from John Adams to Abigail Adams, 3 July 1776, ‘Had a Declaration…’. Adams Family Papers. Massachusetts Historical Society. Архивировано из первоисточника 25 августа 2011. Проверено 28 июня 2009.

- ↑ Maier, Pauline. Making Sense of the Fourth of July. American Heritage (7 августа 1997). Архивировано из первоисточника 25 августа 2011. Проверено 28 июня 2009.

- ↑ Burnett Edward Cody. The Continental Congress. — Нью-Йорк: W.W. Norton, 1941. — P. 191–96.

- ↑ Warren, Charles. (Июль 1945). «Fourth of July Myths». The William and Mary Quarterly 2 (3): 238–272.

- ↑ Top 5 Myths About the Fourth of July!. History News Network. George Mason University (30 июня 2001). Проверено 28 июня 2009.

- ↑ Becker Carl L. The Declaration of Independence: A Study in the History of Political Ideas. — Нью-Йорк: Harcourt, Brace, 1922. — С. 184-185.

- ↑ Не многие учёные считают, что декларация действительно была подписана 4 июля, см. Wilfred J. Ritz, «The Authentication of the Engrossed Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776». Law and History Review 4, № 1 (Весна 1986): 179—204.

- ↑ Heintze, James R. Fourth of July Celebrations Database. — Вашингтон: American University.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 Heintze, James R. A Chronology of Notable Fourth of July Celebration Occurrences. — Вашингтон: American University.

- ↑ July Events — 4th of July in Maine (англ.). maine.info (Июля 2010). Архивировано из первоисточника 17 октября 2012. Проверено 2 октября 2012.

- ↑ Heintze, James R. How the Fourth of July was Designated as an ‘Official’ Holiday. — Вашингтон: American University.

- ↑ Heintze, James R. Federal Legislation Establishing the Fourth of July Holiday. — Вашингтон: American University.

- ↑ 1 2 Biggest fireworks show in U.S. lights up sky (англ.). USA Today (7 апреля 2009). Архивировано из первоисточника 17 октября 2012. Проверено 2 октября 2012.

- ↑ Музыка ко Дню независимости США отражает историю и разнообразную культуру страны (рус.). america.gov (5 июля 2007 года). Архивировано из первоисточника 25 августа 2011. Проверено 7 ноября 2010.

- ↑ Сергей Авдеев. Екатеринбурженка поплатилась за незнание законов США (рус.). Российская газета (19 октября 2007). Проверено 7 ноября 2010.

- ↑ Origin of the 21-Gun Salute. U.S. Army Center of Military History (3 октября 2003). Архивировано из первоисточника 25 августа 2011. Проверено 28 июня 2009.

- ↑ Фейерверки в городах США на День Независимости (рус.). photo-finish.ru (8 июля 2010). Архивировано из первоисточника 25 августа 2011. Проверено 7 ноября 2010.

- ↑ AAA Chicago Projects Increase in Fourth of July Holiday Travelers (англ.). prnewswire.com (23 июня 2010). Архивировано из первоисточника 17 октября 2012. Проверено 2 октября 2012.

- ↑ Bristol Fourth of July Celebration History (англ.). Официальный сайт парада. Архивировано из первоисточника 25 августа 2011. Проверено 7 ноября 2010.

- ↑ History. Rebild Society. Rebild National Park Society. Архивировано из первоисточника 25 августа 2011. Проверено 30 июня 2009.

- ↑ Nathan’s Famous Hot Dog Eating Contest (англ.). Официальный сайт чемпионата. Архивировано из первоисточника 25 августа 2011. Проверено 7 ноября 2010.

- ↑ Bill Garrison. Фестиваль свободы (англ.). flagspot.net (29 июля 2007). Архивировано из первоисточника 25 августа 2011. Проверено 7 ноября 2010.

- ↑ Календарь (англ.). Официальный сайт главной бейсбольной лиги (4 июля 2009). Архивировано из первоисточника 25 августа 2011. Проверено 7 ноября 2010.

- ↑ 2009 Macy’s 4th of July Fireworks. Federated Department Stores (29 апреля 2009). Архивировано из первоисточника 25 августа 2011. Проверено 4 июля 2009.

- ↑ Peachtree Road Race 10 km (англ.). arrs.net. Архивировано из первоисточника 25 августа 2011. Проверено 7 ноября 2010.

- ↑ Boston Pops Fireworks Spectacular. CBS (2007). Архивировано из первоисточника 25 августа 2011. Проверено 4 июля 2009.

- ↑ A Capital Fourth (англ.). Официальный сайт. Архивировано из первоисточника 25 августа 2011. Проверено 7 ноября 2010.

Литература

- Becker Carl L. The Declaration of Independence: A Study in the History of Political Ideas. — New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1922.

- Heintze, James R Fourth of July Celebrations Database. American University of Washington, D.C. Архивировано из первоисточника 25 августа 2011. Проверено 4 июля 2007.

Ссылки

- Парад по случаю дня независимости

- U.S. Independence Day a Civic and Social Event U.S. State Department, June 22, 2010

- The Meaning of July Fourth for the Negro by Frederick Douglass

|

Федеральные праздники США |

|---|

|

День Нового года • День Мартина Лютера Кинга • Президентский день • День памяти • День независимости • День Труда • День Колумба • День ветеранов • День благодарения • Рождество Христово |

![New York City's fireworks display, shown above over the East Village, is sponsored by Macy's and is the largest[32] in the country.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f9/Fireworks_over_the_East_Village_of_New_York_City.JPG/200px-Fireworks_over_the_East_Village_of_New_York_City.JPG)