Вот что пишется даже в лояльных к марксизму источниках об инквизиции:

Новая инквизиция

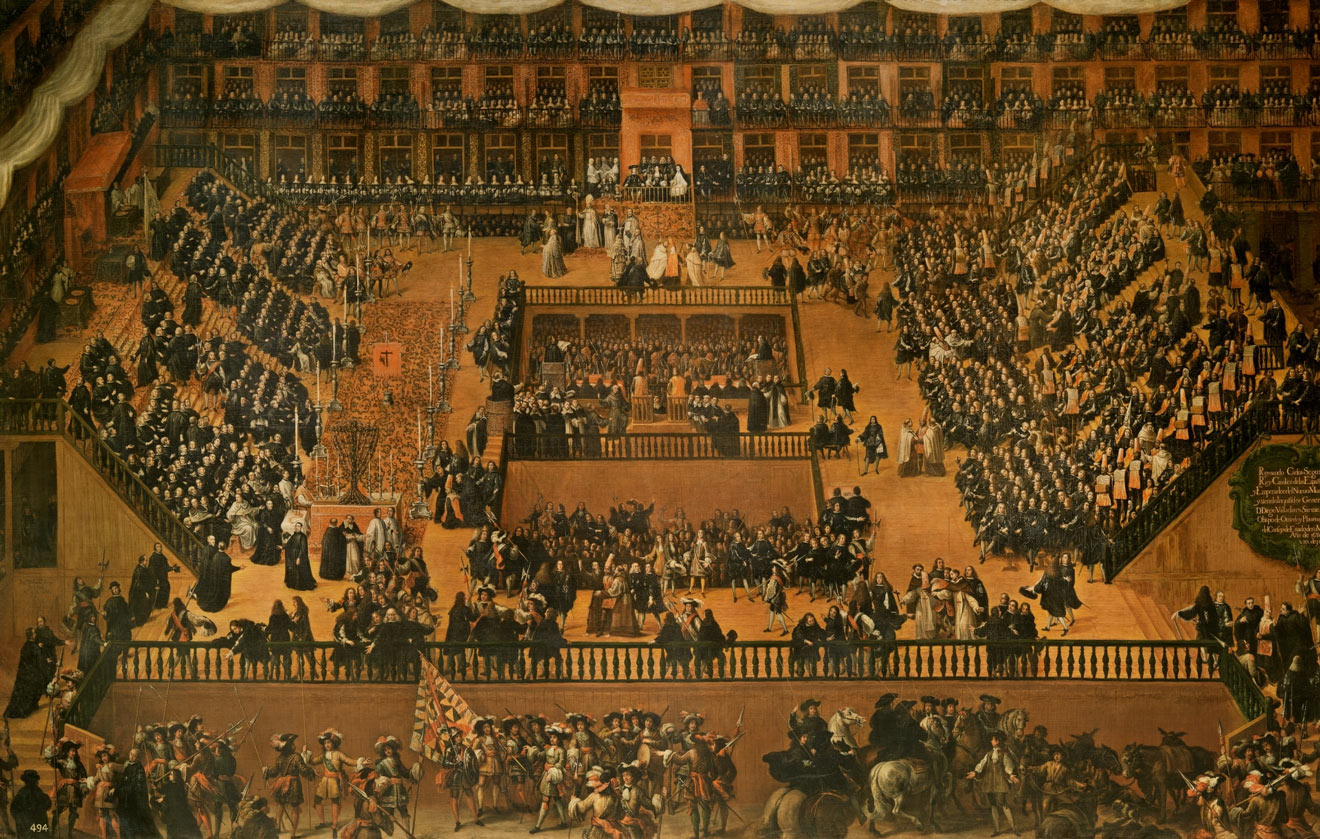

XV-XVI вв. в истории Испании, — это начало кризиса феодального миропорядка. Инквизиция, в этой ситуации, была последней надеждой церкви сохранить потерянное господство. Томас де Торквемада убеждает королей объединенного государства Кастилии и Арагоны Изабеллу и Фердинанда в том, что Новая инквизиция должна укрепить королевскую власть. Новая инквизиция становится грозным оружием абсолютизма в руках власти под прикрытием внутренних вооруженных сил – Святой Германдады.В 1480 г. появились первые инквизиторы: Мигель де Морильо и Хуан де Сан Мартин. В 1482 г. папа утверждает 8 новых инквизиторов, среди которых был и Томас де Торквемада.

Ведьмы

В XVI-XVII вв. Европу поразила «охота на ведьм» — безумие, связанное с вымыслами о ведьмах, колдунах и т. д. Суды над ведьмами постепенно переходят в ведение церкви, а затем папской инквизиции. Ужесточаются наказания, ведьм все чаще отправляют на костер. Стала появляться литература на тему ведьм, в том числе «Молот ведьм» (1487), и буллы как священные уставы, в их числе знаменитая Булла «Summis desiderantes». «Молот ведьм» собрал в себя все народные предания, и стал наставлением для инквизиторов Европы.

Ведьмы описываются уродливыми старухами, чья деятельность обычно направлена на силы природы, когда же изображаются они молодыми девушками, соблазняющими мужчин. Практически все данные известные о ведьмах на сегодняшний день взяты из двух источников. Самый главный источник это показания самих ведьм на пытках. Осужденные, надеявшиеся на снисхождение, готовы были признаться в чем угодно, тем более что нередко они и сами верили в эти истории под психологическим прессингом инквизиции. [- автор очень спешит сделать вывод за читателя, немедленно]. Другие данные, дошедшие до нашего времени основаны на искусстве тех времен.

Заключая пакт с демоном, ведьмы отрекались от христианской церкви, дьявол оставлял на ее теле какой-либо знак, и женщина становилась полноправным членом дьявольского общества. Также известны конкретные даты массовых сборищ ведьм, так называемых шабашей, и очень подробные описания полета на метле и рецепты мазей для этих полетов, которые состояли в основном из наркотических веществ, что многое объясняет [- это объясняет, что помимо сексуальных услуг в арсенале «услад» БАБСКИХ притонов-шабошей были наркотики]. Очень красочно устами ведьм описываются сами шабаши, которые состояли из танцев, трапезы и пародию на католическое богослужение.

Охота на ведьм в Европе поднимала в народе злобу, ненависть и страх. Она совпадала с эпохой Возрождения и выражала в себе противодействие сил прогресса и старых мировоззрений, этот факт объясняет еще и то, что по всей Европе завязались кровопролитные войны представителей разных направлений христианства за свою религию. И ведьмы служили «камнем преткновения» этих взаимоборствующих сил, на который можно было свалить всю вину. В течение 2 с лишним столетий эта эпидемия безумия охватывала все страны Европы, и за это время было осуждено в среднем 200000 человек. Закончилась эта стихия тогда, когда в ведомстве стали обвинять членов семьи правительства.

Удивительно, что во время этой лихорадки Испания и ее инквизиция скромнее всего себя проявили, дело в том, что у них в то время были более существенные враги, такие как евреи, мориски и протестанты.

Запомним указанные даты и поговорим теперь не об «эпидемии безумия», а совсем о другой эпидемии.

Другие ученые (их называют «американистами») считают, что «венерическую болезнь» в Европу завезли в конце XV века моряки Христофора Колумба из только что открытой тогда Америки. «Американисты» в качестве обоснования «американского» происхождения сифилиса в Европе приводят следующие доводы: во-первых, узнали о сифилисе в Европе только тогда, когда это заболевание приняло эпидемический характер и очень быстро распространилось по всему Европейскому континенту; во-вторых, упомянутая эпидемия совпала по времени с возвращением на родину моряков экспедиции Христофора Колумба [- по большому счёту, пофигу КАК появилось и с чем «совпало», главное, КОГДА началась ЭПИДЕМИЯ вензаболеваний]…в 1493 году.Продвижению сифилиса по Европе способствовали частые в то время войны. Как свидетельствуют историки, в 1494 году во время осады Неаполя войсками французского короля Карла VIII, которая длилась около 80 дней, около 14000 проституток «обслуживали» солдат королевской армии. В войсках французов вспыхнула неизвестная болезнь, которая заставила Карла VIII заключить мир.

Возвращаясь, домой, солдаты разноплеменного наемного войска французского короля вместе с походным ранцем несли своим женам и невестам неведомое доселе заболевание. Отсутствие эффективных средств и методов лечения, культурная отсталость, процветание проституции способствовали распространению начавшейся эпидемии, которая сопровождалась многочисленными жертвами и особой тяжестью течения болезни.

Сведения о неслыханном раньше заболевании приблизительно в эти же годы появились и в России, которая была связана с Западной Европой торговыми отношениями. Великий князь Иоанн Васильевич (Иван III) в 1499 году, прослышав о «новой болезни», наказывал посланному в Литву боярскому сыну Ивану Мамонову: «…Пытати… в Вязьме князя Бориса, в Вязьму кто, не проезживал ли болен из Смоленска тою болестью, что болячки мечются, а словеть франчюжска, а будто из Вильны ее привезли, да и в Смоленску о том пытати, еще ли болесть есть или нет…».

Очень длительное время «нехорошая болезнь» не имела своего названия и именовалась у французов неаполитанской, у итальянцев — французской. Называли ее еще и испанской, и египетской. Упомянутая эпидемия, только что появившейся в Европе болезни, несомненно, подтвердила, что основной причиной и «французской», и «испанской», и «итальянской» болезни является половая несдержанность.

Вероятно, уже с тех пор вытекло стремление скрывать свое заболевание, как полученное постыдным образом в связи с половой распущенностью, хотя венерические болезни могут передаваться и неполовым путем (в результате тесного, иногда бытового контакта).

В качестве персонажа поэмы (1530 г.), на котором описывались симптомы «новой болезни», врачом и поэтом Джироламо Фракасторо был взят свинопас Сифилюс, которого за разврат бог Аполлон наказал болезнью половых органов. Название «новой болезни» — «сифилис» сохранилось до наших дней, хотя происхождение его так и осталось невыясненным. То ли оно произошло от греческих «сие» (свинья) и «филиа» (любовь) — «свинская любовь», то ли от «сифлос» (пятнающий, калечащий) в сочетании с «филиа» (любовь).

Поначалу всякая болезнь, связанная с поражением половых органов, относилась к сифилису и считалась симптомом этого заболевания. Так, долгое время и гонорею, и мягкий шанкр, являющиеся самостоятельными болезнями, трактовали как проявления сифилиса.

Итак, что же получается. В Европе времён Средневековья не было никаких медицинских органов, способных грамотно справляться с эпидемией вензаболеваний. На всё про всё для подобных задач был один орган – церковный, именно в его ведении находился вопрос «здоровья общества». И, не смотря на отсутствие многих медицинских знаний, дураками в то время люди отнюдь не были. (Более того, ввиду отсутствия компьютеров и калькуляторов, они, возможно, лучше считали в уме, чем мы))).

Если уж вылечить саму болезнь методов не было, то вычислить, как она распространяется и КЕМ, служители церкви были способны вполне. После чего сделать правильные (щадящие общество) выводы и принять соответствующие времени адекватные меры. Надеюсь, все понимают, что я имею в виду.

А теперь посмотрим кое-какие заметки про наше настоящее:

Основным же фактом, который даже скептиков должен убедить, что риск заражения весьма вероятен, если не соблюдать мер профилактики, тот факт, что, к большому сожалению, число заболевших венерическими болезнями прогрессивно растет везде. В России ситуация с венерическими заболеваниями носит характер эпидемии. Причин этому несколько:

— Сексуальная революция. Изменение сексуального поведения не повлекло за собой изменения у людей правил и гигиены сексуальных отношений;

— Появление различных контрацептивов резко снизило страх возникновения нежелательной беременности. Соответственно, исчезновение этого страха снимает ограничения в половой жизни;

— В настоящее время медицинская помощь доступна практически всем. Эта доступность а также уверенность, что венерические болезни как классические так и новые излечимы, и потому не очень опасны также сыграла свою роль. Но не все так гладко и просто.

— Нормы сексуальной жизни в России, такие как «Заниматься сексом в презервативе это все равно, что вдыхать аромат цветов в противогазе», не добавляют культуры к сексуальным отношениям в отношении профилактики венерических болезней.

— Как это не удивительно, скрытность пациентов в вопросах половой жизни на приеме у врача — также одна из причин эпидемии. Такое поведение не позволяет вовремя выявить и вылечить заболевшего и его половых партнеров.

Если к этому добавить вездесущее феминистическое «моё тело – моё дело!» и защиту блядства законом, то очевидно, что для борьбы с нынешними эпидемиями могут понадобиться меры, не слабее инквизиции. Если, конечно, эти эпидемии не входят в план правительства по геноциду народа.

Мы все зажжем свечу и вспомним тех, кто умирал в муках, мы их вспомним, чтобы кощунственно не забыть Время зла религий на Земле, чтобы оно не вернулось и религии со своими извращениями и садизмом ушли с Земли, уступив место Вере.

Монастырские тюрьмы

Как известно, такие тюрьмы с давних пор существовали при некоторых из наших монастырей. Особенно широкой известностью пользовалась в обществе тюрьма Соловецкого монастыря, куда в прежние времена ссылались не только религиозные, но и государственные преступники, которые по терминологии той эпохи величались «ворами и бунтовщиками». Ссылка в Соловецкий монастырь религиозных и государственных преступников широко практиковалась уже в половине XVI столетия, в царствование Иоанна Грозного. Затем, в течение XVII, XVIII и первой половины XIX столетия тюрьма Соловецкого монастыря нередко была переполнена заключенными.

Вероятно, этим последним обстоятельством следует объяснить, что во второй половине XVIII столетия возникает новая монастырская тюрьма или крепость — на этот раз в центре России, а именно в Спасо-Евфимиевом монастыре, находящемся в г. Суздаль, Владимирской губернии.

Разоблачение злодеяний

Палаческие обязанности монастырь выполнял около четырехсот лет… В земляных ямах, в крепостных казематах гноили, доводили людей до умопомешательства. По жестокости режима соловецкий острог не имел себе равных. Сами цари замуровывали туда опасных врагов абсолютизма. Острог был также основной тюрьмой духовного ведомства, пока в подмогу не возникло «арестантское отделение» в Суздальском Спасо-Евфимиевом монастыре, самом вместительном…

В кремле было семь башень (по Фруменкову — восемь). На запрос Синода в 1742 году архимандрит признал наличие земляных тюрем в башнях: Корожней, Головленковой, у Никитских ворот и в Салтыковой, да имелись еще тюрьмы под келарской службой и под Преображенским собором.

Вот размеры тюрем, указанные архимандритом и признанные историками: в Корожней длиною и шириною в 4 аршина (2м 85см на 2м 85см), в Головленковой, первая — длиною 5 аршин и шириною 4 аршина (3м 55см на 2м 85см), вторая, как в Корожней: 4 на 4 аршина, у Никольских ворот: первая — около 4 арш. длиною и чуть больше 6 арш. шириною (2м 85см на 4м 26см) и вторая длиною 5 арш. и шириною около 6 арш. (3м 55см на 4м 26 см) и, наконец, в Салтыковой — длиною 6 арш., шириною менее 3 арш. (4м 26см на 2м 13см).

При таких размерах эти тюрьмы могли быть устроены или под башнями, или перед башнями. В самых башнях и в городовой стене имелись только маленькие одиночки, казематы, вот эти самые «каменные мешки». Более трех аршин в длину (2м 13см) их нельзя было сделать (да и не требовалось по тому назначению — хранить боеприпасы — для которого их построил зодчий — монах Трифон). По Богуславскому каменные мешки.

Земляные тюрьмы появились много позже Трифона, когда стали присылать арестантов с указом «заключить в земляную тюрьму, неисходно, до кончины живота, под крепким караулом».

Человек в яме содержался согнутым, без света и прикованным, помещался в яму мученик после истязаний, где его потихоньку поедали крысы. Особенно предпочитал эту форму наказания, как замену смертной казни, Петр Преобразователь. Он сам дважды навещал Соловки: в 1694 и в 1702 году с флотом против шведов. «Петр со своей свитой в 1702 голу — пишет Богуславский — неоднократно был в монастыре, осматривал ризницу, Оружейную палату, монастырские службы и ТЮРЬМЫ (разрядка моя. М. Р.), посетил кирпичный завод». Следовательно, царь на месте убедился, что его указы о заточении в земляные тюрьмы (тогда и были только такие) исполняются неукоснительно. Тут же на пригорке за бухтой Петр поставил каменный столб с указанием, сколько верст отсюда до Венеции — града (3900), Мадрида, Рима, до Камчатки, Вены, Лондона и Берлина. При нас, в двадцатых и тридцатых годах, этот столб еще стоял с потускневшими надписями, а потом кому-то помешал.

Последний правительственный указ о заключении в земляную тюрьму издан 7 июня 1739 года относительно князя Мещерского, а через три года последовал особый указ монастырю засыпать все «монастырские ямы для колодников». Такие тюрьмы представляли собой в земле яму глубиной до 2 метров, обложенную по стенам кирпичей, а сверху покрытую Дощатым настилом, на который насыпалась земля. В таком погребе на охапке сена без печки не перезимуешь. Конечно окоченели там многие. Историки не скрывают, что в таких условиях некоторые узники выживали годами и да еще «опущенные туда закованными в железа или с вырванными ноздрями.

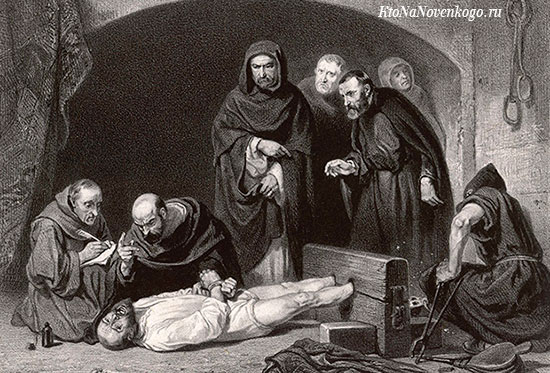

Сейчас я хочу рассказать и показать вам лишь некоторые орудия пыток.

Средневековье считается периодом в истории с самым безжалостным отношением к людям. За малейшую провинность их подвергали изощренным пыткам. В этом обзоре представлено 13 орудий для пыток, которые заставят людей признаться в чем угодно.

1. «Груша страданий».

Этот жестокий инструмент использовался для наказания женчин, сделавших аборт, лжецов и гомосексуалистов. Устройство вставлялось во влагалище у женчин или задний проход у мужчин. Когда палач крутил винт, «лепестки» раскрывались, разрывая плоть и принося жертвам невыносимые мучения. Многие умирали затем от заражения крови.

2. Дыба.

К деревянной раме за руки и ноги привязывали жертву и растягивали конечности в противоположные стороны. Поначалу разрывались хрящевые ткани, а потом вырывались конечности. Чуть позже на раму крепились шипы, которые впивались в спину жертве. Для усиления болей шипы смазывались солью.

3. «Колесо Екатерины».

Прежде, чем привязать жертву к колесу, ей ломали конечности. При вращении ноги и руки окончательно выламывались, принося жертве невыносимые мучения. Одни умирали от болевого шока, а другие мучились по нескольку дней.

4. Труба-«крокодил».

Ноги или лицо жертвы (иногда и то и другое) помещались внутрь этой трубы, тем самым обездвиживая ее. Палач постепенно нагревал железо, заставляя признаться людей в чем угодно.

5. Медный бык.

Жертву помещали в медную статую быка, под которым был разведен костер. Человек умирал от ожогов и удушья. Во время пытки крики, доносящиеся изнутри, напоминали мычание быка.

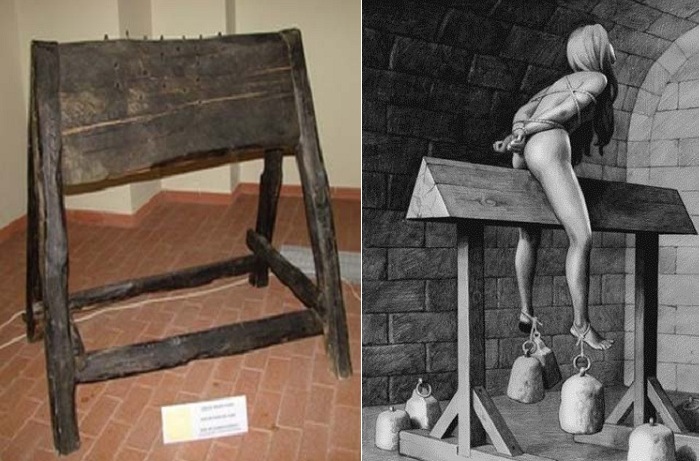

6. Испанский осел.

Деревянное бревно в виде треугольника закреплялось на «ножках». Голая жертва помещалась сверху на острый угол, который врезался прямо в промежность. Чтобы пытка становился более невыносимой, к ногам привязывали утяжелители.

7. Пыточный гроб.

Жертвы помещались в металлические клетки, которые их полностью обездвиживали. Если пыточные гробы приходились людям не по размеру, это доставляло им дополнительные мучения. Смерть эта была долгой и мучительной. Птицы клевали плоть жертв, а толпа кидала в них камни.

8. Дробилка головы

Голова несчастного зажималась под этим «колпаком». Палач медленно закручивал винты, и верхняя часть «дробилки» давила на череп. Первой ломалась челюсть, выпадали зуба. После этого выдавливались глаза, а напоследок, ломался череп.

9. «Кошачья лапа».

«Кошачьей лапой» пользовались для того, чтобы разодрать плоть до костей.

10. Дробитель колена.

Это орудие пыток было особенно популярным во времена инквизиции. Колено жертвы помещалось между зубцами. Когда палач закручивал винты, зубцы вонзались в плоть, а затем дробили коленный сустав. После такой пытки встать но ноги уже не представлялось возможным.

11. «Колыбель Иуды».

Одно из самых жестоких пыток носило название «Колыбель Иуды» или «Стул Иуды». Жертву принудительно опускали на железную пирамиду. Острие попадала прямо в задний проход или влагалище. Полученные разрывы через некоторое время приводили к смерти.

12. Грудные «когти».

Это орудие пыток применялось для женчин, которые обвинялись в супружеской неверности. «Когти» нагревали, а затем вонзали в грудь жертве. Если женчина не умирала, то на всю жизнь она оставалась с ужасными шрамами.

13. «Ругательная уздечка».

Эта своеобразная железная маска использовалась для наказания сварливых женчин. Внутри нее могли быть шипы, а в отверстии для рта пластина, которая накладывалась на язык, чтоб жертва не могла говорить. Обычно женчину проводили по шумным площадям. Колокольчик, закрепленный на маске, привлекал всеобщее внимание, побуждая толпу смеяться над той, которую наказывали.

Средневековые пытки — это ужасное явление. Все это применялось к красивым женчинам, девочкам с 9 лет. Мученица обнажалась, чем доставляла удовольствие монахам извращенцам. Женчин религии не любили никогда, считая их любовницами Дьявола. Под пытки попадали и ученые, и врачи, и ведающие люди, так как религии отрицали какие-либо знания кроме религиозных доктрин. Встает вопрос, как после стольких лет геноцида народа во всех странах, религии сумели заставить поклоняться их богам и оморочили разум людей. В каждом Роду есть пострадавшие от монастырских тюрем или пыток и сегодня, входя в ту или иную религию, вы поклоняетесь садизму и предаете память своих предков, а религии вкрадчиво говорят вам о традициях, но традиции не имеют ничего общего с религией. Об этом я рассказывала на сайте Вера.

Мне хочется сказать всем тем, кто сейчас в любой религии. Вы своей энергией кормите, а значит держите на Земле Матери садистов!

Инквизиция позади, но за религиозных богов все еще мучают и убивают, все террористические акты идут во имя бога, с богом идут на войну, строится церковь, посвященная войне и никто этого не замечает. А жертвы баранами, а законы стран, где процветает ислам (не могу писать с большой буквы). Когда все очнутся, будет очень стыдно за то, что жили и убивали ради религии, а не Создателя. Создателю войны и смерти не нужны.

Пусть зажженная свеча услышит ваш голос, а рядом положите белый хлеб и молоко

«Поминаем убиенных в страшных муках, поминаем и религии за зло проклинаем, и с Земли их прогоняем. По праву человека на Земле живущего, Слово мое зовущее, Силу Земли призываю, религии изгоняю. Да будут в помощь мне все, кто в муках пыток с земли ушел. Заклинаю.»

Говорите 9 или 40 раз.

В группах ИСВ в социальных сетях также есть помин.

Глава ИСВ, Алена Полынь

28 апреля 2021История, Антропология

Кто такие средневековые инквизиторы? За кем они охотились? Действительно ли существовали ведьмы? Их сжигали на кострах? Сколько всего людей было уничтожено?

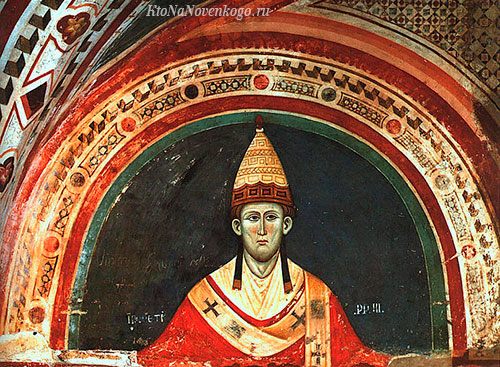

1. Что значит слово «инквизиция» и кто его придумал?

Это латинское слово inquisitio, которое означает «расследование», «розыск», «сыск». Инквизиция нам известна как церковный институт, но первоначально это понятие обозначало тип уголовного процесса. В отличие от обвинения (accusatio) и доноса (denunciatio), когда дело заводилось в результате, соответственно, открытого обвинения или тайного доноса, в случае inquisitio суд сам начинал процесс на основании заведомых подозрений и запрашивал у населения подтверждающую информацию. Придумали этот термин юристы в поздней Римской империи, а в Средние века он утвердился в связи с рецепцией, то есть открытием, изучением и усвоением в XII столетии, основных памятников римского права.

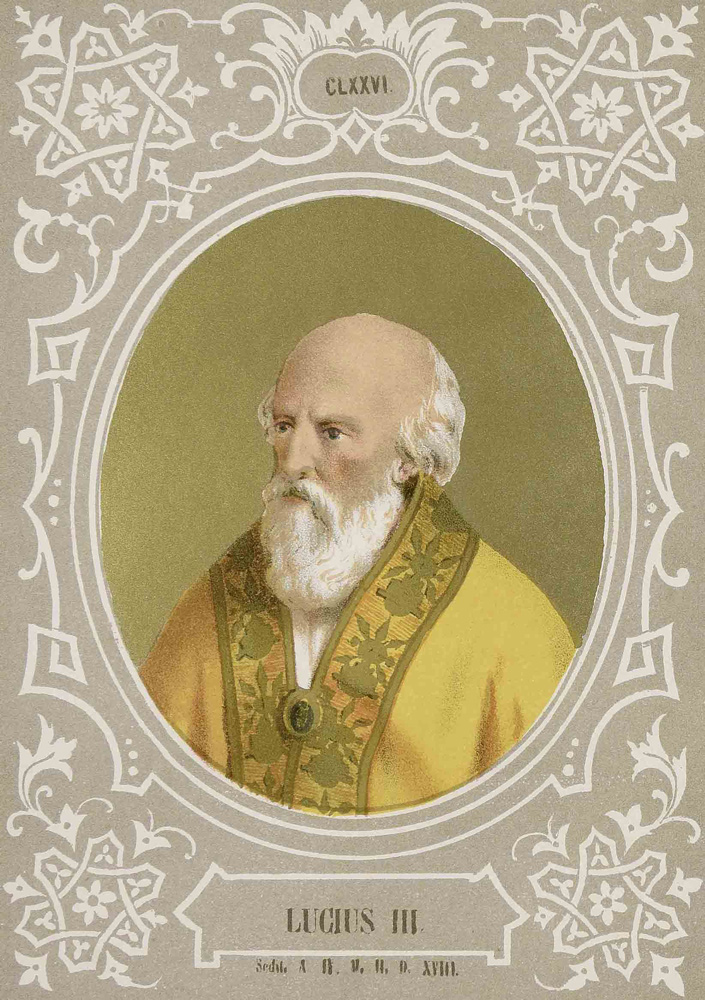

Судебный розыск практиковал как королевский суд — например, в Англии, — так и Церковь, причем в борьбе не только с ересью, но и с другими преступлениями, входившими в юрисдикцию церковных судов, в том числе с блудом и двоеженством. Но самой мощной, стабильной и известной формой церковного inquisitio стал inquisitio hereticae pravitatis, то есть розыск еретической скверны Так, например, называлось руководство для инквизиторов, написанное французским инквизитором Бернаром Ги — тем самым, который фигурирует в «Имени Розы» Умберто Эко.. В этом значении инквизицию придумал папа Люций III, который в конце XII века обязал епископов искать еретиков, несколько раз в год объезжая свою епархию и расспрашивая достойных доверия местных жителей о подозрительном поведении их соседей.

2. Почему ее называют святой?

Инквизицию не всегда и не везде называли святой. Этого эпитета нет в приведенном выше словосочетании «розыск еретической скверны», как нет его в официальном названии высшего органа испанской инквизиции — Совета верховной и генеральной инквизиции. Центральное управление папской инквизиции, созданное в ходе реформы папской курии в середине XVI века, действительно называлось Верховная священная конгрегация римской и вселенской инквизиции, но слово «священная» точно так же входило в полные названия и других конгрегаций, или отделов, курии — например, Священная конгрегация таинств или Священная конгрегация Индекса.

В то же время в обиходе и в разного рода документах инквизицию начинают называть Sanctum officium — в Испании Santo oficio, — что переводится как «святая канцелярия», или «ведомство», или «служба». В первой половине ХХ века это словосочетание вошло в название римской конгрегации, и в таком контексте этот эпитет не вызывает удивления: инквизиция подчинялась святому престолу и занималась защитой святой католической веры, делом не то что святым, а практически божественным. Так, например, первый историк инквизиции — сам сицилийский инквизитор — Луис де Парамо начинает историю религиозного сыска с изгнания из рая, делая первым инквизитором самого Господа: он расследовал грех Адама и наказал его соответственно.

3. Что за люди становились инквизиторами и кому они подчинялись?

Поначалу, на протяжении нескольких десятилетий, папы пытались поручить инквизицию епископам и даже угрожали снятием с должности тем, кто будет халатно относиться к очищению своей епархии от еретической заразы. Но епископы оказались не очень приспособлены к этой задаче: они были заняты своими рутинными обязанностями, а главное, бороться с ересью им мешали налаженные социальные связи, прежде всего с местной знатью, которая иногда открыто покровительствовала еретикам. Тогда, в начале 1230-х годов, папа поручил розыск еретиков монахам нищенствующих орденов — доминиканцам и францисканцам. Они обладали рядом достоинств, необходимых в этом деле: были преданы папе, не зависели от местного духовенства и сеньоров и нравились народу своей показательной бедностью и нестяжательством. Монахи соперничали с еретическими проповедниками и обеспечивали содействие населения в деле поимки еретиков. Инквизиторы были наделены обширными полномочиями и не зависели ни от местных церковных властей, ни от папских посланников — легатов. Напрямую они подчинялись только папе, свои полномочия получали пожизненно и в любых форс-мажорных ситуациях могли отправиться в Рим, чтобы апеллировать к папе. Кроме того, инквизиторы могли оправдывать друг друга, так что сместить инквизитора, а тем более отлучить его от Церкви было почти невозможно.

4. Где существовала инквизиция?

Инквизиция — с конца XII века епископская, а с 1230-х годов — папская, или доминиканская, — появилась в Южной Франции. Примерно тогда же ее ввели в соседней Короне Арагона Корона Арагона — пиренейская федеративная монархия, куда входили Арагон, Каталония и Валенсия, а также некоторые острова, южнофранцузские и итальянские земли. Существовала с 1162 года до объединения с Кастилией в конце XV — начале XVI века. Де-юре название и некоторые институты (например, кортесы) просуществовали до начала XVIII века.. И там и там стояла проблема искоренения ереси катаров: это дуалистическое учение, пришедшее с Балкан и распространившееся чуть ли не по всей Западной Европе, было особенно популярно по обе стороны Пиренеев. После антиеретического Крестового похода 1215 года катары ушли в подполье — и тут меч оказался бессилен, потребовалась длинная и цепкая рука церковного сыска.

На протяжении XIII века по папской инициативе инквизицию вводили в разных итальянских государствах, причем в Ломбардии и Генуе инквизицией ведали доминиканцы, а в Центральной и Южной Италии — францисканцы. Ближе к концу века инквизиция была учреждена в Неаполитанском королевстве, на Сицилии и в Венеции. В XVI веке, в эпоху Контрреформации Контрреформация — консервативная реорганизация учения и структуры Римско-католической церкви, проводимая в связи с распространением протестантизма., итальянская инквизиция, возглавленная первой конгрегацией папской курии, заработала с новой силой, борясь с протестантами и всякого рода вольнодумцами.

В Германской империи время от времени действовали инквизиторы-доминиканцы, но постоянных трибуналов не было — из-за многовекового конфликта между императорами и папами и административной раздробленности империи, затруднявшей любые инициативы на общегосударственном уровне. В Чехии действовала епископская инквизиция, но, по-видимому, она была не слишком эффективна — по крайней мере, искоренять ересь гуситов, последователей Яна Гуса, сожженного в 1415 году чешского реформатора Церкви, командировали специалистов из Италии.

В конце XV века новая, или королевская, инквизиция возникла в объединенной Испании — впервые в Кастилии и заново в Арагоне, в начале XVI века — в Португалии, а в 1570-х годах и в колониях — Перу, Мексике, Бразилии, Гоа.

5. Почему самая известная инквизиция — испанская?

Вероятно, из-за черного пиара. Дело в том, что инквизиция стала центральным элементом так называемой «черной легенды» о габсбургской Испании как отсталой и мракобесной стране, где заправляют чванливые гранды Гранды — высшая знать в средневековой Испании. и фанатичные доминиканцы. «Черную легенду» распространяли как политические противники Габсбургов, так и жертвы — или потенциальные жертвы — инквизиции. Среди них были крещеные евреи — марраны, эмигрировавшие с Пиренейского полуострова, например, в Голландию и культивировавшие там память о своих собратьях, мучениках инквизиции; испанские протестанты-эмигранты и иностранные протестанты; жители неиспанских владений испанской короны: Сицилии, Неаполя, Нидерландов, а также Англии во время брака Марии Тюдор и Филиппа II, которые либо возмущались введением у себя инквизиции по испанскому образцу, либо только опасались этого; французские просветители, которые видели в инквизиции воплощение средневекового мракобесия и католического засилья. Все они в своих многочисленных сочинениях — от газетных памфлетов до исторических трактатов — долго и упорно создавали образ испанской инквизиции как страшного монстра, угрожающего всей Европе. Наконец, к концу XIX века, уже после упразднения инквизиции и во время распада колониальной империи и глубокого кризиса в стране, демонический образ святой канцелярии усвоили сами испанцы и стали винить инквизицию во всех своих проблемах. Консервативный католический мыслитель Марселино Менендес-и-Пелайо так пародировал этот ход либеральной мысли: «Почему нет промышленности в Испании? Из-за инквизиции. Почему испанцы ленивы? Из-за инквизиции. Почему сиеста? Из-за инквизиции. Почему коррида? Из-за инквизиции».

6. За кем охотились и как определяли, кого казнить?

В разные периоды и в разных странах инквизицию интересовали разные группы населения. Объединяло их то, что все они так или иначе отступали от католической веры, тем самым губя свои души и нанося «урон и оскорбление» этой самой вере. В Южной Франции это были катары, или альбигойцы, в Северной — вальденсы, или лионские бедняки, еще одна антиклерикальная ересь, стремившаяся к апостольской бедности и праведности. Кроме того, французская инквизиция преследовала отступников в иудаизм и спиритуалов — радикальных францисканцев, очень серьезно относившихся к обету бедности и критически — к Церкви. Иногда инквизиция участвовала в политических процессах вроде процесса над рыцарями-тамплиерами, обвиняемыми в ереси и поклонении дьяволу, или Жанной д’Арк, обвиняемой примерно в том же; на самом деле и те, и другая представляли политическую помеху или угрозу для, соответственно, короля и английских оккупантов. В Италии имелись свои катары, вальденсы и спиритуалы, позже распространилась ересь дольчинистов, или апостольских братьев: они ожидали второго пришествия в ближайшем будущем и проповедовали бедность и покаяние. Испанская инквизиция занималась прежде всего «новыми христианами» преимущественно еврейского, а также мусульманского происхождения, немногочисленными протестантами, гуманистами из университетов, ведунами и ведьмами и мистиками из движения алумбрадо («просвещенных»), которые стремились к единению с Богом по собственному методу, отвергая церковные практики. Инквизиция эпохи Контрреформации преследовала протестантов и различных вольнодумцев, а также женщин, подозреваемых в колдовстве.

курс

Жанна д’Арк: история мифа

Как и почему менялось отношение к Средним векам и их героям

Кого казнить — точнее, кого судить, — определяли путем сбора информации у населения. Начиная розыск в новом месте, инквизиторы объявляли так называемый срок милосердия, обычно месяц, когда сами еретики могли покаяться и выдать сообщников, а «добрые христиане» под страхом отлучения обязаны были донести обо всем, что знали. Получив достаточно сведений, инквизиторы начинали вызывать подозреваемых, которые должны были доказывать свою невиновность (действовала презумпция виновности); как правило, им это не удавалось, и они попадали в темницу, где подвергались допросам и пыткам.

Казнили далеко не сразу и не так уж часто. Оправдание было практически невозможно и заменялось вердиктом «обвинение не доказано». Большинство сознавшихся и раскаявшихся осужденных получали так называемое «примирение» с Церковью, то есть оставались в живых, искупая грехи постами и молитвами, нося позорящую одежду (в Испании так называемое санбенито — скапулярий — монашескую накидку желтого цвета с изображением крестов Сантьяго Крест Сантьяго — крест с удлиненным и заостренным основанием, называемый также «крест-меч», распространенный пиренейский геральдический символ.), иногда отправляясь на принудительные работы или в тюрьму, зачастую лишаясь имущества. Лишь небольшой процент осужденных — в Испании, например, от 1 до 5 % — «отпускали», то есть предавали в руки светской власти, которая их и казнила. Сама инквизиция как церковный институт смертных приговоров не выносила, ибо «Церковь не знает крови». «Отпускали» на казнь еретиков, упорствующих в своих заблуждениях, то есть не покаявшихся и не давших признательных показаний, не оговоривших других людей. Или «рецидивистов», вторично впавших в ересь.

7. Инквизиторы могли обвинить короля или, например, кардинала?

Инквизиции были подсудны все: в случае подозрения в ереси иммунитет монархов или церковных иерархов не действовал, однако осудить людей такого ранга мог только сам папа. Известны случаи апелляции высокопоставленных обвиняемых к папе и попытки вывода дела из-под юрисдикции инквизиции. Например, дон Санчо де ла Кабальерия, арагонский гранд еврейского происхождения, известный своей враждой к инквизиции, нарушающей дворянские иммунитеты, был арестован по обвинению в содомии. Он заручился поддержкой архиепископа Сарагосского и пожаловался на арагонскую инквизицию в Супрему — верховный совет испанской инквизиции, а затем и в Рим. Дон Санчо настаивал на том, что содомия не входит в юрисдикцию инквизиции, и пытался перевести свое дело в суд архиепископа, но инквизиция получила соответствующие полномочия от папы и не отпускала его. Процесс длился несколько лет и ничем не закончился — дон Санчо умер в заточении.

8. Ведьмы действительно были или просто сжигали красивых женщин?

Вопрос о реальности колдовства, очевидно, выходит за пределы компетенции историка. Скажем так, многие — как гонители, так и жертвы и их современники — верили в реальность и эффективность чародейства. А ренессансный мизогинизм полагал его типично женским видом деятельности. Самый знаменитый антиведовской трактат «Молот ведьм» объясняет, что женщины — существа излишне эмоциональные и недостаточно разумные. Во-первых, они часто отступают от веры и поддаются влиянию дьявола, а во-вторых, легко ввязываются в ссоры и склоки и, ввиду своей физической и юридической слабости, в качестве защиты прибегают к колдовству.

Ведьмами «назначали» не обязательно молодых и красивых, хотя молодых и красивых тоже — в этом случае обвинение в ведовстве отражало страх мужчин (особенно, вероятно, монахов) перед женскими чарами. За сговор с дьяволом судили и пожилых повитух и знахарок — здесь причиной мог быть страх клириков перед чуждым для них знанием и авторитетом, которым такие женщины пользовались в народе. Наконец, ведьмами оказывались одинокие и бедные женщины — самые слабые члены общины. Согласно теории британского антрополога Алана Макфарлейна, охота на ведьм в Англии при Тюдорах и Стюартах, то есть в XVI–XVII веках, была вызвана социальными изменениями — распадом общины, индивидуализацией и имущественным расслоением в деревне, когда богатые, чтобы оправдать свое состояние на фоне бедности односельчан, в частности одиноких женщин, стали обвинять их в колдовстве. Охота на ведьм была средством решения коммунальных конфликтов и снижения социального напряжения в целом. Испанская инквизиция охотилась на ведьм гораздо реже — там функцию козла отпущения выполняли «новые христиане», причем чаще «новые христианки», которых, помимо иудействования, походя, бывало, обвиняли и в склочности, и в колдовстве.

9. Почему ведьм именно сжигали?

Церковь, как известно, не должна проливать кровь, поэтому сожжение после удушения выглядело предпочтительнее, а кроме того, оно иллюстрировало евангельский стих: «Кто не пребудет во Мне, извергнется вон, как ветвь, и засохнет; а такие ветви собирают и бросают в огонь, и они сгорают» Ин. 15:6.. В действительности инквизиция не осуществляла казни собственноручно, а «отпускала» непримиренных еретиков в руки светской власти. А согласно светским законам, принятым в Италии, а затем в Германии и во Франции в течение XIII века, ересь каралась лишением прав, конфискацией собственности и сожжением на костре.

10. Правда ли, что обвиняемых постоянно пытали, пока не признаются?

Не без этого. Хотя каноническое право запрещало использование пыток в церковном судопроизводстве, в середине XIII века папа Иннокентий IV специальной буллой легитимировал пытки при расследовании ереси, приравняв еретиков к разбойникам, которых подвергали пыткам в светских судах. Как мы уже сказали, Церковь не должна была проливать кровь, кроме того, запрещалось нанесение тяжких увечий, поэтому выбирали пытки на растяжение тела и разрыв мускулов, на зажим тех или иных частей тела, на раздробление суставов, а также пытки водой, огнем и каленым железом. Пытку разрешалось применять лишь единожды, но это правило обходили, объявляя каждую новую пытку возобновлением предыдущей.

тест

Какой вы еретик?

Пройдите допрос виртуального инквизитора, чтобы выяснить, в какую ересь вы впали

11. Сколько всего людей сожгли?

По всей видимости, не так много, как можно подумать, но число жертв трудно подсчитать. Если говорить об испанской инквизиции, ее первый историк Хуан Антонио Льоренте, сам генеральный секретарь мадридской инквизиции, высчитал, что за три с лишним века своего существования святая канцелярия обвинила 340 тысяч человек, а на сожжение отправила 30 тысяч, то есть примерно 10 %. Эти цифры уже много раз пересматривались, в основном в сторону уменьшения. Статистические изыскания затруднены тем, что архивы трибуналов пострадали, сохранились не все и частично. Архив Супремы с отчетами по рассмотренным делам, которые ежегодно отправляли все трибуналы, сохранился лучше. Как правило, есть данные по некоторым трибуналам за определенные периоды, и эти данные экстраполируют на прочие трибуналы и на все остальное время. Однако при экстраполяции снижается точность, потому что, вероятнее всего, кровожадность менялась в сторону снижения. На основании отчетов, посылаемых в Супрему, подсчитано, что с середины XVI по конец XVII века инквизиторы в Кастилии и Арагоне, на Сицилии и Сардинии, в Перу и Мексике рассмотрели 45 тысяч дел и сожгли не менее полутора тысяч человек, то есть около 3 %, но из них половину — в изображении То есть обвиняемый был в бегах, его судили заочно и в случае осуждения на смерть сжигали не самого человека, а его изображение.. Не менее — потому что информация по многим трибуналам имеется лишь за часть этого периода, но представление о порядке можно составить. Даже если увеличить эту цифру вдвое и допустить, что за первые 60 и последние 130 лет своей деятельности инквизиция уничтожила столько же, до 30 тысяч, названных Льоренте, будет далеко.

Римская инквизиция раннего Нового времени рассмотрела, как считается, 50–70 тысяч дел, при этом отправила на казнь около 1300 человек. Охота на ведьм была более разрушительной — здесь насчитывают несколько десятков тысяч сожженных. Но в целом инквизиторы старались «примирять», а не «отпускать».

12. Как к инквизиции относился простой народ?

Обличители инквизиции, конечно, считали, что она порабощает народ, сковывает его страхом, а тот в ответ ее ненавидит. «В Испании, от страха онемелой, / Царили Фердинанд и Изабелла, / И царствовал железною рукою / Великий инквизитор над страною» Перевод Бориса Томашевского., — писал американский поэт Генри Лонгфелло. Современные исследователи-ревизионисты опровергают такое видение инквизиции, в том числе мысль о насилии над испанским народом, указывая на то, что по своей кровожадности она заметно уступала германским и английским светским судам, расправлявшимся с еретиками и ведьмами, или французским преследователям гугенотов, а также на то, что сами испанцы никогда, вплоть до революции 1820 года, как будто не имели ничего против инквизиции. Известны случаи, когда люди пытались перекинуться под ее юрисдикцию, считая ее предпочтительнее светского суда, и действительно, если посмотреть на дела не марранов и морисков Мориски — в Испании и Португалии мусульмане, официально принявшие христианство, а также их потомки., а «старых христиан» из числа простого народа, обвиняемых, например, в богохульстве по невежеству, неотесанности или пьянству, то наказания были довольно мягкими: сколько-то ударов плетью, изгнание из епархии на несколько лет, заточение в монастыре.

13. Когда инквизиция закончилась?

А она и не закончилась — только поменяла вывеску. Конгрегация инквизиции (в первой половине ХХ века — Конгрегация священной канцелярии) на Втором Ватиканском соборе 1965 года была переименована в Конгрегацию вероучения, которая существует по сей день и занимается защитой веры и нравственности католиков, в частности расследует сексуальные преступления духовенства и цензурирует сочинения католических теологов, противоречащие церковной доктрине.

Если говорить про испанскую инквизицию, то в XVIII веке ее деятельность пошла на спад, в 1808 году инквизицию отменил Жозеф Бонапарт. Во время реставрации испанских Бурбонов после французской оккупации она была восстановлена, отменена во время «свободного трехлетия» 1820–1823 годов, вновь введена вернувшимся на французских штыках королем и уже окончательно упразднена в 1834 году.

Современная инквизиция

Ватиканский журналист Якопо Скарамуцци — о Конгрегации доктрины веры

микрорубрики

Ежедневные короткие материалы, которые мы выпускали последние три года

Архив

This article is about the Inquisition within the Catholic Church. For other uses, see Inquisition (disambiguation).

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, but convictions of unrepentant heresy were handed over to the secular courts, which generally resulted in execution or life imprisonment.[1][2][3] The Inquisition had its start in the 12th-century Kingdom of France, with the aim of combating religious deviation (e.g. apostasy or heresy), particularly among the Cathars and the Waldensians. The inquisitorial courts from this time until the mid-15th century are together known as the Medieval Inquisition. Other groups investigated during the Medieval Inquisition, which primarily took place in France and Italy, include the Spiritual Franciscans, the Hussites, and the Beguines. Beginning in the 1250s, inquisitors were generally chosen from members of the Dominican Order, replacing the earlier practice of using local clergy as judges.[4]

During the Late Middle Ages and the early Renaissance, the scope of the Inquisition grew significantly in response to the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation. During this period, the Inquisition conducted by the Holy See was known as the Roman Inquisition. The Inquisition also expanded to other European countries,[5] resulting in the Spanish Inquisition and the Portuguese Inquisition. The Spanish and Portuguese Inquisitions focused particularly on the anusim (people who were forced to abandon Judaism against their will) and on Muslim converts to Catholicism. The scale of the persecution of converted Muslims and converted Jews in Spain and Portugal was the result of suspicions that they had secretly reverted to their previous religions, although both religious minority groups were also more numerous on the Iberian Peninsula than in other parts of Europe.

During this time, Spain and Portugal operated inquisitorial courts not only in Europe, but also throughout their empires in Africa, Asia, and the Americas. This resulted in the Goa Inquisition, the Peruvian Inquisition, and the Mexican Inquisition, among others.[6]

With the exception of the Papal States, the institution of the Inquisition was abolished in the early 19th century, after the Napoleonic Wars in Europe and the Spanish American wars of independence in the Americas. The institution survived as part of the Roman Curia, but in 1908 it was renamed the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office. In 1965, it became the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.[7]

Definition and purpose[edit]

The term «Inquisition» comes from the Medieval Latin word inquisitio, which described any court process based on Roman law, which had gradually come back into use during the Late Middle Ages.[8] Today, the English term «Inquisition» can apply to any one of several institutions that worked against heretics (or other offenders against canon law) within the judicial system of the Roman Catholic Church. Although the term «Inquisition» is usually applied to ecclesiastical courts of the Catholic Church, it refers to a judicial process, not an organization. Inquisitors ‘…were called such because they applied a judicial technique known as inquisitio, which could be translated as «inquiry» or «inquest».’ In this process, which was already widely used by secular rulers (Henry II used it extensively in England in the twelfth century), an official inquirer called for information on a specific subject from anyone who felt he or she had something to offer.»[9]

The Inquisition, as a church-court, had no jurisdiction over Muslims and Jews as such.[10] Generally, the Inquisition was concerned only with the heretical behaviour of Catholic adherents or converts.[11]

The overwhelming majority of sentences seem to have consisted of penances like wearing a cross sewn on one’s clothes or going on pilgrimage.[1] When a suspect was convicted of unrepentant heresy, canon law required the inquisitorial tribunal to hand the person over to secular authorities for final sentencing. A secular magistrate, the «secular arm», would then determine the penalty based on local law.[12][13] Those local laws included proscriptions against certain religious crimes, and the punishments included death by burning, although the penalty was more usually banishment or imprisonment for life, which was generally commuted after a few years. Thus the inquisitors generally knew the fate which expected anyone so remanded.[14]

The 1578 edition of the Directorium Inquisitorum (a standard Inquisitorial manual) spelled out the purpose of inquisitorial penalties: … quoniam punitio non refertur primo & per se in correctionem & bonum eius qui punitur, sed in bonum publicum ut alij terreantur, & a malis committendis avocentur (translation: «… for punishment does not take place primarily and per se for the correction and good of the person punished, but for the public good in order that others may become terrified and weaned away from the evils they would commit»).[15]

Origin[edit]

Before 1100, the Catholic Church suppressed what they believed to be heresy, usually through a system of ecclesiastical proscription or imprisonment, but without using torture,[5] and seldom resorting to executions.[16][17] Such punishments were opposed by a number of clergymen and theologians, although some countries punished heresy with the death penalty.[18][19] Pope Siricius, Ambrose of Milan, and Martin of Tours protested against the execution of Priscillian, largely as an undue interference in ecclesiastical discipline by a civil tribunal. Though widely viewed as a heretic, Priscillian was executed as a sorcerer. Ambrose refused to give any recognition to Ithacius of Ossonuba, «not wishing to have anything to do with bishops who had sent heretics to their death».[20]

In the 12th century, to counter the spread of Catharism, prosecution of heretics became more frequent. The Church charged councils composed of bishops and archbishops with establishing inquisitions (the Episcopal Inquisition). The first Inquisition was temporarily established in Languedoc (south of France) in 1184. The murder of Pope Innocent’s papal legate Pierre de Castelnau in 1208 sparked the Albigensian Crusade (1209–1229). The Inquisition was permanently established in 1229 (Council of Toulouse), run largely by the Dominicans[21] in Rome and later at Carcassonne in Languedoc.

Medieval Inquisition[edit]

Historians use the term «Medieval Inquisition» to describe the various inquisitions that started around 1184, including the Episcopal Inquisition (1184–1230s) and later the Papal Inquisition (1230s). These inquisitions responded to large popular movements throughout Europe considered apostate or heretical to Christianity, in particular the Cathars in southern France and the Waldensians in both southern France and northern Italy. Other Inquisitions followed after these first inquisition movements. The legal basis for some inquisitorial activity came from Pope Innocent IV’s papal bull Ad extirpanda of 1252, which explicitly authorized (and defined the appropriate circumstances for) the use of torture by the Inquisition for eliciting confessions from heretics.[22] However, Nicholas Eymerich, the inquisitor who wrote the «Directorium Inquisitorum», stated: ‘Quaestiones sunt fallaces et ineficaces’ («interrogations via torture are misleading and futile»). By 1256 inquisitors were given absolution if they used instruments of torture.[23]

In the 13th century, Pope Gregory IX (reigned 1227–1241) assigned the duty of carrying out inquisitions to the Dominican Order and Franciscan Order. By the end of the Middle Ages, England and Castile were the only large western nations without a papal inquisition.

Most inquisitors were friars who taught theology and/or law in the universities. They used inquisitorial procedures, a common legal practice adapted from the earlier Ancient Roman court procedures.[24] They judged heresy along with bishops and groups of «assessors» (clergy serving in a role that was roughly analogous to a jury or legal advisers), using the local authorities to establish a tribunal and to prosecute heretics. After 1200, a Grand Inquisitor headed each Inquisition. Grand Inquisitions persisted until the mid 19th century.[25]

Early Modern European history[edit]

With the sharpening of debate and of conflict between the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation, Protestant societies came to see/use the Inquisition as a terrifying «Other»,[26] while staunch Catholics regarded the Holy Office as a necessary bulwark against the spread of reprehensible heresies.

Witch-trials[edit]

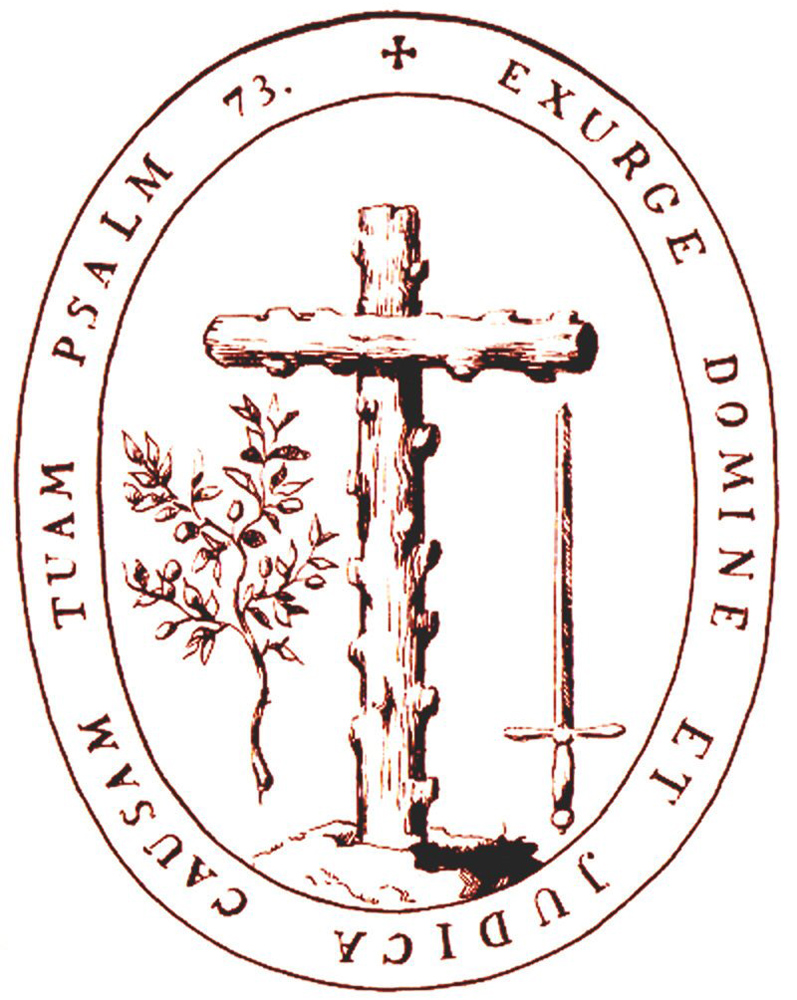

Emblem of the Spanish Inquisition (1571)

While belief in witchcraft, and persecutions directed at or excused by it, were widespread in pre-Christian Europe, and reflected in Germanic law, the influence of the Church in the early medieval era resulted in the revocation of these laws in many places, bringing an end to traditional pagan witch hunts.[27] Throughout the medieval era, mainstream Christian teaching had denied the existence of witches and witchcraft, condemning it as pagan superstition.[28] However, Christian influence on popular beliefs in witches and maleficium (harm committed by magic) failed to entirely eradicate folk belief in witches.

The fierce denunciation and persecution of supposed sorceresses that characterized the cruel witchhunts of a later age were not generally found in the first thirteen hundred years of the Christian era.[29] The medieval Church distinguished between «white» and «black» magic.[citation needed] Local folk practice often mixed chants, incantations, and prayers to the appropriate patron saint to ward off storms, to protect cattle, or ensure a good harvest. Bonfires on Midsummer’s Eve were intended to deflect natural catastrophes or the influence of fairies, ghosts, and witches. Plants, often harvested under particular conditions, were deemed effective in healing.[30]

Black magic was that which was used for a malevolent purpose. This was generally dealt with through confession, repentance, and charitable work assigned as penance.[31] Early Irish canons treated sorcery as a crime to be visited with excommunication until adequate penance had been performed. In 1258, Pope Alexander IV ruled that inquisitors should limit their involvement to those cases in which there was some clear presumption of heretical belief.

The prosecution of witchcraft generally became more prominent in the late medieval and Renaissance era, perhaps driven partly by the upheavals of the era – the Black Death, the Hundred Years War, and a gradual cooling of the climate that modern scientists call the Little Ice Age (between about the 15th and 19th centuries). Witches were sometimes blamed.[32][33] Since the years of most intense witch-hunting largely coincide with the age of the Reformation, some historians point to the influence of the Reformation on the European witch-hunt.[34]

Dominican priest Heinrich Kramer was assistant to the Archbishop of Salzburg. In 1484 Kramer requested that Pope Innocent VIII clarify his authority to prosecute witchcraft in Germany, where he had been refused assistance by the local ecclesiastical authorities. They maintained that Kramer could not legally function in their areas.[35]

The papal bull Summis desiderantes affectibus sought to remedy this jurisdictional dispute by specifically identifying the dioceses of Mainz, Köln, Trier, Salzburg, and Bremen.[36] Some scholars view the bull as «clearly political».[37] The bull failed to ensure that Kramer obtained the support he had hoped for. In fact he was subsequently expelled from the city of Innsbruck by the local bishop, George Golzer, who ordered Kramer to stop making false accusations. Golzer described Kramer as senile in letters written shortly after the incident. This rebuke led Kramer to write a justification of his views on witchcraft in his 1486 book Malleus Maleficarum («Hammer against witches»). In the book, Kramer stated his view that witchcraft was to blame for bad weather. The book is also noted for its animus against women.[29] Despite Kramer’s claim that the book gained acceptance from the clergy at the University of Cologne, it was in fact condemned by the clergy at Cologne for advocating views that violated Catholic doctrine and standard inquisitorial procedure. In 1538 the Spanish Inquisition cautioned its members not to believe everything the Malleus said.[38]

Spanish Inquisition[edit]

Portugal and Spain in the late Middle Ages consisted largely of multicultural territories of Muslim and Jewish influence, reconquered from Islamic control, and the new Christian authorities could not assume that all their subjects would suddenly become and remain orthodox Roman Catholics. So the Inquisition in Iberia, in the lands of the Reconquista counties and kingdoms like León, Castile, and Aragon, had a special socio-political basis as well as more fundamental religious motives.[40]

In some parts of Spain towards the end of the 14th century, there was a wave of violent anti-Judaism, encouraged by the preaching of Ferrand Martínez, Archdeacon of Écija. In the pogroms of June 1391 in Seville, hundreds of Jews were killed, and the synagogue was completely destroyed. The number of people killed was also high in other cities, such as Córdoba, Valencia, and Barcelona.[41]

One of the consequences of these pogroms was the mass conversion of thousands of surviving Jews. Forced baptism was contrary to the law of the Catholic Church, and theoretically anybody who had been forcibly baptized could legally return to Judaism. However, this was very narrowly interpreted. Legal definitions of the time theoretically acknowledged that a forced baptism was not a valid sacrament, but confined this to cases where it was literally administered by physical force. A person who had consented to baptism under threat of death or serious injury was still regarded as a voluntary convert, and accordingly forbidden to revert to Judaism.[42] After the public violence, many of the converted «felt it safer to remain in their new religion».[43] Thus, after 1391, a new social group appeared and were referred to as conversos or New Christians.

King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile established the Spanish Inquisition in 1478. In contrast to the previous inquisitions, it operated completely under royal Christian authority, though staffed by clergy and orders, and independently of the Holy See. It operated in Spain and in most[44] Spanish colonies and territories, which included the Canary Islands, the Kingdom of Sicily,[45] and all Spanish possessions in North, Central, and South America. It primarily focused upon forced converts from Islam (Moriscos, Conversos and secret Moors) and from Judaism (Conversos, Crypto-Jews and Marranos)—both groups still resided in Spain after the end of the Islamic control of Spain—who came under suspicion of either continuing to adhere to their old religion or of having fallen back into it.

In 1492 all Jews who had not converted were expelled from Spain; those who converted became nominal Catholics and thus subject to the Inquisition.

Inquisition in the Spanish overseas empire[edit]

In the Americas, King Philip II of Spain set up three tribunals (each formally titled Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición) in 1569, one in Mexico, Cartagena de Indias (in modern-day Colombia) and Peru. The Mexican office administered Mexico (central and southeastern Mexico), Nueva Galicia (northern and western Mexico), the Audiencias of Guatemala (Guatemala, Chiapas, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica), and the Spanish East Indies. The Peruvian Inquisition, based in Lima, administered all the Spanish territories in South America and Panama.[citation needed]

Portuguese Inquisition[edit]

A copper engraving from 1685: «Die Inquisition in Portugall»

The Portuguese Inquisition formally started in Portugal in 1536 at the request of King João III. Manuel I had asked Pope Leo X for the installation of the Inquisition in 1515, but only after his death in 1521 did Pope Paul III acquiesce. At its head stood a Grande Inquisidor, or General Inquisitor, named by the Pope but selected by the Crown, and always from within the royal family.[citation needed] The Portuguese Inquisition principally focused upon the Sephardi Jews, whom the state forced to convert to Christianity. Spain had expelled its Sephardi population in 1492; many of these Spanish Jews left Spain for Portugal but eventually were subject to inquisition there as well.

The Portuguese Inquisition held its first auto-da-fé in 1540. The Portuguese inquisitors mostly focused upon the Jewish New Christians (i.e. conversos or marranos). The Portuguese Inquisition expanded its scope of operations from Portugal to its colonial possessions, including Brazil, Cape Verde, and Goa. In the colonies, it continued as a religious court, investigating and trying cases of breaches of the tenets of orthodox Roman Catholicism until 1821. King João III (reigned 1521–57) extended the activity of the courts to cover censorship, divination, witchcraft, and bigamy. Originally oriented for a religious action, the Inquisition exerted an influence over almost every aspect of Portuguese society: political, cultural, and social.

According to Henry Charles Lea, between 1540 and 1794, tribunals in Lisbon, Porto, Coimbra, and Évora resulted in the burning of 1,175 persons, the burning of another 633 in effigy, and the penancing of 29,590.[46] But documentation of 15 out of 689 autos-da-fé has disappeared, so these numbers may slightly understate the activity.[47]

Inquisition in the Portuguese overseas empire[edit]

Goa Inquisition[edit]

The Goa Inquisition began in 1560 at the order of John III of Portugal. It had originally been requested in a letter in the 1540s by Jesuit priest Francis Xavier, because of the New Christians who had arrived in Goa and then reverted to Judaism. The Goa Inquisition also focused upon Catholic converts from Hinduism or Islam who were thought to have returned to their original ways. In addition, this inquisition prosecuted non-converts who broke prohibitions against the public observance of Hindu or Muslim rites or interfered with Portuguese attempts to convert non-Christians to Catholicism.[48] Aleixo Dias Falcão and Francisco Marques set it up in the palace of the Sabaio Adil Khan.

Brazilian Inquisition[edit]

The inquisition was active in colonial Brazil. The religious mystic and formerly enslaved prostitute, Rosa Egipcíaca was arrested, interrogated and imprisoned, both in the colony and in Lisbon. Egipcíaca was the first black woman in Brazil to write a book — this work detailed her visions and was entitled Sagrada Teologia do Amor Divino das Almas Peregrinas.[49]

Roman Inquisition[edit]

With the Protestant Reformation, Catholic authorities became much more ready to suspect heresy in any new ideas,[50]

including those of Renaissance humanism,[51] previously strongly supported by many at the top of the Church hierarchy. The extirpation of heretics became a much broader and more complex enterprise, complicated by the politics of territorial Protestant powers, especially in northern Europe. The Catholic Church could no longer exercise direct influence in the politics and justice-systems of lands that officially adopted Protestantism. Thus war (the French Wars of Religion, the Thirty Years’ War), massacre (the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre) and the missional[52] and propaganda work (by the Sacra congregatio de propaganda fide)[53] of the Counter-Reformation came to play larger roles in these circumstances, and the Roman law type of a «judicial» approach to heresy represented by the Inquisition became less important overall. In 1542 Pope Paul III established the Congregation of the Holy Office of the Inquisition as a permanent congregation staffed with cardinals and other officials. It had the tasks of maintaining and defending the integrity of the faith and of examining and proscribing errors and false doctrines; it thus became the supervisory body of local Inquisitions.[54] A famous case tried by the Roman Inquisition was that of Galileo Galilei in 1633.

The penances and sentences for those who confessed or were found guilty were pronounced together in a public ceremony at the end of all the processes. This was the sermo generalis or auto-da-fé.[55] Penances (not matters for the civil authorities) might consist of a pilgrimage, a public scourging, a fine, or the wearing of a cross. The wearing of two tongues of red or other brightly colored cloth, sewn onto an outer garment in an «X» pattern, marked those who were under investigation. The penalties in serious cases were confiscation of property by the Inquisition or imprisonment. This led to the possibility of false charges to enable confiscation being made against those over a certain income, particularly rich marranos. Following the French invasion of 1798, the new authorities sent 3,000 chests containing over 100,000 Inquisition documents to France from Rome.

Ending of the Inquisition in the 19th and 20th centuries[edit]

By decree of Napoleon’s government in 1797, the Inquisition in Venice was abolished in 1806.[56]

In Portugal, in the wake of the Liberal Revolution of 1820, the «General Extraordinary and Constituent Courts of the Portuguese Nation» abolished the Portuguese inquisition in 1821.

The wars of independence of the former Spanish colonies in the Americas concluded with the abolition of the Inquisition in every quarter of Hispanic America between 1813 and 1825.

The last execution of the Inquisition was in Spain in 1826.[57] This was the execution by garroting of the school teacher Cayetano Ripoll for purportedly teaching Deism in his school.[57] In Spain the practices of the Inquisition were finally outlawed in 1834.[58]

In Italy, the restoration of the Pope as the ruler of the Papal States in 1814 brought back the Inquisition to the Papal States. It remained active there until the late-19th century, notably in the well-publicised Mortara affair (1858–1870). In 1908 the name of the Congregation became «The Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office», which in 1965 further changed to «Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith», as retained to the present day.

Statistics[edit]

Beginning in the 19th century, historians have gradually compiled statistics drawn from the surviving court records, from which estimates have been calculated by adjusting the recorded number of convictions by the average rate of document loss for each time period. Gustav Henningsen and Jaime Contreras studied the records of the Spanish Inquisition, which list 44,674 cases of which 826 resulted in executions in person and 778 in effigy (i.e. a straw dummy was burned in place of the person).[59] William Monter estimated there were 1000 executions between 1530–1630 and 250 between 1630 and 1730.[60] Jean-Pierre Dedieu studied the records of Toledo’s tribunal, which put 12,000 people on trial.[61] For the period prior to 1530, Henry Kamen estimated there were about 2,000 executions in all of Spain’s tribunals.[62] Italian Renaissance history professor and Inquisition expert Carlo Ginzburg had his doubts about using statistics to reach a judgment about the period. «In many cases, we don’t have the evidence, the evidence has been lost,» said Ginzburg.[63]

Appearance in popular media[edit]

- In the Monty Python comedy team’s Spanish Inquisition sketches, an inept Inquisitor group repeatedly bursts into scenes after someone utters the words «I didn’t expect a kind of Spanish Inquisition», screaming «Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition!» The Inquisition then uses ineffectual forms of torture, including a dish-drying rack, soft cushions and a comfy chair.

- The 1982 novel Baltasar and Blimunda by José Saramago, portrays how the Portuguese Inquisition impacts the fortunes of the title characters as well as several others from history, including the priest and aviation pioneer Bartolomeu de Gusmão.

- The 1981 comedy film History of the World, Part I, produced and directed by Mel Brooks, features a segment on the Spanish Inquisition.

- Inquisitio is a French television series set in the Middle Ages.

- In the novel Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco, there is some discussion about various sects of Christianity and inquisition, a small discussion about the ethics and purpose of inquisition, and a scene of Inquisition. In the movie by the same name, The Inquisition plays a prominent role including torture and a burning at the stake.

- In the novel La Catedral del Mar by Ildefonso Falcones, and Netflix series Cathedral of the Sea based on the novel, there are scenes of inquisition investigations in small towns and a great scene in Barcelona.

- Miloš Forman’s «Goya’s Ghosts», released June 9, 2007 in the US, brings to light the stories behind some of Spanish painter Francisco Goya’s paintings during the Spanish Inquisition, particularly one of a priest condemning and imprisoning a beautiful woman for his own profit. Her family retaliates, but cannot save her.

- A fictionalized version of the Inquisition serves as a basis for the action-adventure horror stealth game A Plague Tale: Innocence.

- In the Assassin’s Creed series, the Spanish Inquisition is controlled by the Templar Order, the nemesis of the Assassins.

See also[edit]

- Auto-da-fé

- Black legend (Spain)

- Black Legend of the Spanish Inquisition

- Cathars

- List of people executed in the Papal States

- Witch-cult hypothesis

- Witch trials in the early modern period

- Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith

- Historical revision of the Inquisition

- Marian Persecutions of Protestant heretics

Documents and works[edit]

- Directorium Inquisitorum

- Histoire de l’Inquisition en France

- Malleus Maleficarum

Notable inquisitors[edit]

- List of Grand Inquisitors

- Konrad von Marburg

- Tomás de Torquemada

- Bernardo Gui

Notable cases[edit]

- Trial of Galileo Galilei

- Execution of Giordano Bruno

- Trial of Joan of Arc

- Edgardo Mortara’s abduction

- Logroño witch trials

- Caterina Tarongí

- Rosa Egipcíaca

Repentance[edit]

- Apologies by Pope John Paul II

References[edit]

- ^ a b «Internet History Sourcebooks Project». legacy.fordham.edu. Archived from the original on 20 March 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ Peters, Edwards. «Inquisition», p. 67.

- ^ Lea, Henry Charles. «Chapter VII. The Inquisition Founded». A History of the Inquisition In The Middle Ages. Vol. 1. ISBN 1-152-29621-3. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

- ^ Peters, Edward. «Inquisition», p. 54.

- ^ a b

Lea, Henry Charles (1888). «Chapter VII. The Inquisition Founded». A History of the Inquisition In The Middle Ages. Vol. 1. ISBN 1-152-29621-3.The judicial use of torture was as yet happily unknown…

- ^ Murphy, Cullen (2012). God’s Jury. New York: Mariner Books – Houghton, Mifflin, Harcourt. p. 150.

- ^ «Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith — Profile». Vatican.va. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ Peters, Edwards. «Inquisition», p. 12

- ^ «Internet History Sourcebooks Project». Fordham.edu. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ Marvin R. O’Connell. «The Spanish Inquisition: Fact Versus Fiction». Ignatiusinsight.com. Archived from the original on 26 March 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ Salomon, H. P. and Sassoon, I. S. D., in Saraiva, Antonio Jose. The Marrano Factory. The Portuguese Inquisition and Its New Christians, 1536–1765 (Brill, 2001), Introduction pp. XXX.

- ^ Peters writes: «When faced with a convicted heretic who refused to recant, or who relapsed into heresy, the inquisitors were to turn him over to the temporal authorities – the «secular arm» – for animadversio debita, the punishment decreed by local law, usually burning to death.» (Peters, Edwards. «Inquisition», p. 67.)

- ^ Lea, Henry Charles. «Chapter VII. The Inquisition Founded». A History of the Inquisition In The Middle Ages. Vol. 1. ISBN 1-152-29621-3. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

Obstinate heretics, refusing to abjure and return to the Church with due penance, and those who after abjuration relapsed, were to be abandoned to the secular arm for fitting punishment.

- ^ Kirsch, Jonathan (9 September 2008). The Grand Inquisitors Manual: A History of Terror in the Name of God. HarperOne. ISBN 978-0-06-081699-5.

- ^ Directorium Inquisitorum, edition of 1578, Book 3, pg. 137, column 1. Online in the Cornell University Collection; retrieved 2008-05-16.

- ^ Foxe, John. «Chapter monkey» (PDF). Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-11-26. Retrieved 2010-08-31.

- ^

Blötzer, J. (1910). «Inquisition». The Catholic Encyclopedia. Ava Rojas Company. Retrieved 2012-08-26.… in this period the more influential ecclesiastical authorities declared that the death penalty was contrary to the spirit of the Gospel, and they themselves opposed its execution. For centuries this was the ecclesiastical attitude both in theory and in practice. Thus, in keeping with the civil law, some Manichæans were executed at Ravenna in 556. On the other hand, Elipandus of Toledo and Felix of Urgel, the chiefs of Adoptionism and Predestinationism, were condemned by councils, but were otherwise left unmolested. We may note, however, that the monk Gothescalch, after the condemnation of his false doctrine that Christ had not died for all mankind, was by the Synods of Mainz in 848 and Quiercy in 849 sentenced to flogging and imprisonment, punishments then common in monasteries for various infractions of the rule.

- ^

Blötzer, J. (1910). «Inquisition». The Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 2012-08-26.[…] the occasional executions of heretics during this period must be ascribed partly to the arbitrary action of individual rulers, partly to the fanatic outbreaks of the overzealous populace, and in no wise to ecclesiastical law or the ecclesiastical authorities.

- ^

Lea, Henry Charles. «Chapter VII. The Inquisition Founded». A History of the Inquisition In The Middle Ages. Vol. 1. ISBN 1-152-29621-3. - ^ Hughes, Philip (1979). History of the Church Volume 2: The Church In The World The Church Created: Augustine To Aquinas. A&C Black. pp.27-28, ISBN 978-0-7220-7982-9

- ^ «CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Inquisition». Newadvent.org. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ Bishop, Jordan (2006). «Aquinas on Torture». New Blackfriars. 87 (1009): 229–237. doi:10.1111/j.0028-4289.2006.00142.x.

- ^ Larissa Tracy, Torture and Brutality in Medieval Literature: Negotiations of National Identity, (Boydell and Brewer Ltd, 2012), 22; «In 1252 Innocent IV licensed the use of torture to obtain evidence from suspects, and by 1256 inquisitors were allowed to absolve each other if they used instruments of torture themselves, rather than relying on lay agents for the purpose…«.

- ^ Peters, Edwards. «Inquisition», p. 12.

- ^ Lea, Henry Charles. A History of the Inquisition of Spain, vol. 1, appendix 2

- ^

Compare Haydon, Colin (1993). Anti-Catholicism in eighteenth-century England, c. 1714-80: a political and social study. Studies in imperialism. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 6. ISBN 0-7190-2859-0. Retrieved 2010-02-28.The popular fear of Popery focused on the persecution of heretics by the Catholics. It was generally assumed that, whenever it was in their power, Papists would extirpate heresy by force, seeing it as a religious duty. History seemed to show this all too clearly. […] The Inquisition had suppressed, and continued to check, religious dissent in Spain. Papists, and most of all, the Pope, delighted in the slaughter of heretics. ‘I most firmly believed when I was as boy’, William Cobbett [born 1763], coming originally from rural Surrey, recalled, ‘that the Pope was a prodigious woman, dressed in a dreadful robe, which had been made red by being dipped in the blood of Protestants’.

- ^ Hutton, Ronald. The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy. Oxford, UK and Cambridge, US: Blackwell, 1991. ISBN 978-0-631-17288-8. p. 257

- ^ Behringer, Witches and Witch-hunts: A Global History, p. 31 (2004). Wiley-Blackwell.

- ^ a b Thurston, Herbert.»Witchcraft.» The Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol. 15. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 12 Jul. 2015

- ^ «Plants in Medieval Magic – The Medieval Garden Enclosed – The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York». blog.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ Del Rio, Martin Antoine, and Maxwell-Stuart, P. G. Investigations Into Magic, Manchester University Press, 2000, ISBN 9780719049767 p. 7

- ^ Levack, The Witch-Hunt in Early Modern Europe, p. 49

- ^ Heinrich Institoris, Heinrich; Sprenger, Jakob; Summers, Montague. The Malleus maleficarum of Heinrich Kramer and James Sprenger. Dover Publications; New edition, 1 June 1971; ISBN 0-486-22802-9

- ^ Brian P. Levack, The Witch-Hunt in Early Modern Europe (in German) (London/New York 2013 ed.), p. 110,

The period during which all of this reforming activity and conflict took place, the age of the Reformation, spanned the years 1520–1650. Since these years include the period when witch-hunting was most intense, some historians have claimed that the Reformation served as the mainspring of the entire European witch-hunt.»

- ^ Kors, Alan Charles; Peters, Edward. Witchcraft in Europe, 400-1700: A Documentary History. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000. ISBN 0-8122-1751-9. p. 177

- ^ «Internet History Sourcebooks Project». sourcebooks.fordham.edu.

- ^ Darst, David H., «Witchcraft in Spain: The Testimony of Martín de Castañega’s Treatise on Superstition and Witchcraft (1529)», Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 1979, vol. 123, issue 5, p. 298

- ^ Jolly, Raudvere, and Peters (eds.) Witchcraft and magic in Europe: the Middle Ages. 2002. p. 241.

- ^

Saint Dominic Guzmán presiding over an Auto da fe, Prado Museum. Retrieved 2012-08-26 - ^ a b «Secrets of the Spanish Inquisition Revealed». Catholic Answers. Retrieved 2020-10-04.

- ^ Kamen, Spanish Inquisition, p. 17. Kamen cites approximate numbers for Valencia (250) and Barcelona (400), but no solid data about Córdoba.

- ^ Raymond of Peñafort, Summa, lib. 1 p.33, citing D.45 c.5.

- ^ Kamen, Spanish Inquisition, p. 10.

- ^ Aron-Beller, Katherine; Black, Christopher (2018-01-22). The Roman Inquisition: Centre versus Peripheries. BRILL. p. 234. ISBN 978-90-04-36108-9.

- ^ Zeldes, N. (2003). The Former Jews of This Kingdom: Sicilian Converts After the Expulsion 1492-1516. BRILL. p. 128. ISBN 978-90-04-12898-9.

- ^ H.C. Lea, A History of the Inquisition of Spain, vol. 3, Book 8

- ^ Saraiva, António José; Salomon, Herman Prins; Sassoon, I. S. D. (2001) [First published in Portuguese in 1969]. The Marrano Factory: the Portuguese Inquisition and its New Christians 1536-1765. Brill. p. 102. ISBN 978-90-04-12080-8. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- ^ Salomon, H. P. and Sassoon, I. S. D., in Saraiva, Antonio Jose. The Marrano Factory. The Portuguese Inquisition and Its New Christians, 1536–1765 (Brill, 2001), pgs. 345-7

- ^ «Enslaved: Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade». enslaved.org. Retrieved 2021-08-21.

- ^ Stokes, Adrian Durham (2002) [1955]. Michelangelo: a study in the nature of art. Routledge classics (2 ed.). Routledge. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-415-26765-6. Retrieved 2009-11-26.

Ludovico is so immediately settled in heaven by the poet that some commentators have divined that Michelangelo is voicing heresy, that is to say, the denial of purgatory.

- ^ Erasmus, the arch-Humanist of the Renaissance, came under suspicion of heresy, see

Olney, Warren (2009). Desiderius Erasmus; Paper Read Before the Berkeley Club, March 18, 1920. BiblioBazaar. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-113-40503-6. Retrieved 2009-11-26.Thomas More, in an elaborate defense of his friend, written to a cleric who accused Erasmus of heresy, seems to admit that Erasmus was probably the author of Julius.

- ^ Vidmar, John C. (2005). The Catholic Church Through the Ages. New York: Paulist Press. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-8091-4234-7.

- ^ Soergel, Philip M. (1993). Wondrous in His Saints: Counter Reformation Propaganda in Bavaria. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 239. ISBN 0-520-08047-5.

- ^

«Christianity | The Inquisition». The Galileo Project. Retrieved 2012-08-26 - ^ Blötzer, J. (1910). «Inquisition». The Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 2012-08-26.

- ^ «The Public Gardens of Venice and the Inquisition». www.venetoinside.com. Archived from the original on 2020-09-28. Retrieved 2018-09-18.

- ^ a b Law, Stephen (2011). Humanism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-19-955364-8.

- ^ «Spanish Inquisition — Spanish history [1478-1834]». Britannica.com. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ Gustav Henningsen, The Database of the Spanish Inquisition. The relaciones de causas project revisited, in: Heinz Mohnhaupt, Dieter Simon, Vorträge zur Justizforschung, Vittorio Klostermann, 1992, pp. 43-85.

- ^ W. Monter, Frontiers of Heresy: The Spanish Inquisition from the Basque Lands to Sicily, Cambridge 2003, p. 53.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Dedieu, Los Cuatro Tiempos, in Bartolomé Benassar, Inquisición Española: poder político y control social, pp. 15-39.

- ^ H. Kamen, Inkwizycja Hiszpańska, Warszawa 2005, p. 62; and H. Rawlings, The Spanish Inquisition, Blackwell Publishing 2004, p. 15.

- ^ «Vatican downgrades Inquisition toll». Nbcnews.com. 15 June 2004. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

Bibliography[edit]

- Adler, E. N. (April 1901). «Auto de fe and Jew». The Jewish Quarterly Review. University of Pennsylvania Press. 13 (3): 392–437. doi:10.2307/1450541. JSTOR 1450541.

- Burman, Edward, The Inquisition: The Hammer of Heresy (Sutton Publishers, 2004) ISBN 0-7509-3722-X. A new edition of a book first published in 1984, a general history based on the main primary sources.

- Carroll, Warren H., Isabel: the Catholic Queen Front Royal, Virginia, 1991 (Christendom Press)

- Foxe, John (1997) [1563]. Chadwick, Harold J. (ed.). The new Foxe’s book of martyrs/John Foxe; rewritten and updated by Harold J. Chadwick. Bridge-Logos. ISBN 0-88270-672-1.

- Given, James B, Inquisition and Medieval Society (Cornell University Press, 2001)